Correcting the "Europe is Stagnant" Narrative

More nuance in US vs. Europe comparisons

You’ve probably seen some version of these viral graphs, which seem to show Europe in economic stagnation compared to the US:

These kinds triumphalist narratives are naturally popular with American commentators (“Europe is a museum, Japan is a nursing home, China is a jail” as Larry Summers quips); and like anywhere else in the world Europe has its fair share of economic problems.

But I think there’s a more interesting underlying story to tell here — one that does highlight important American strengths and European weaknesses, but also incorporates more nuance and some important strengths in the other direction, too.

Challenging the Myth of Europe's Downfall

The first thing to note about the above graph is that it’s based on current prices, and so incorporates swings in the relative strength of currency markets. A better measure comes from analyzing output per hour adjusting for inflation and purchasing power. This also shows important gaps with the US, but you can see it’s not just a story of total stagnation:

America does much better in GDP per capita overall, but that’s a product of high working hours. It’s not straightforward to translate productivity estimates across different scales of labor supply (would European countries maintain their productivity levels with higher hours worked? Not clear). But it is helpful here to break up “Europe” into several blocks, each of which have distinct but related issues:

Non-Euro Europe: These are countries like Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden, etc. These countries are pretty similar to America in many ways (including home ownership, high productivity, high innovation); but have lower hours and more redistribution (in Scandinavia).

“Core” Europe: These are countries like France, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands. These countries are facing important shocks — services competition from America, increasing manufacturing competition with China, and geopolitical competition with Russia, on top of demographic decline. But they generally have high state capacity, successful firms, and are pushing forward with industrial policy, lots of initiatives on green energy, etc.

“Peripheral” Europe: These include countries like Spain, Italy — and increasingly the UK, which has its own set of issues. These regions also have isolated areas doing well, but alongside other regions that are falling quite far behind. Also seeing deterioration of their industrial base while falling behind in services.

Central and Eastern Europe: These include countries like Poland, Estonia, Czechia, Slovenia — have actually seen convergence happening quickly, and broadly have benefitted enormously from the free flow of goods, capital, and people across Europe, along with European adjustment funds to manage the downsides.

European Firms are Strong

As Adam Tooze points out; the typical narrative of European corporate decline (“Where are all the Apples and Amazons etc”) ignores important areas where European firms have enjoyed meaningful successes, sometimes as a result of private-public sector partnerships or industrial policy.

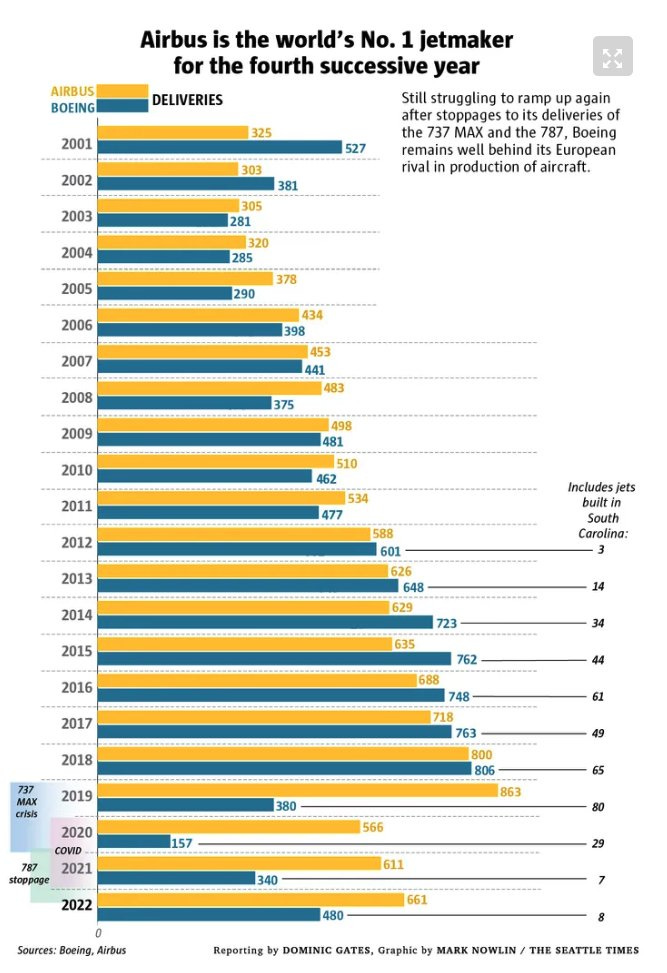

Airbus is one of the biggest examples here — it’s a product of managed state competition, with heavy government subsides, born of multiple consolidations and hosting production all over the place. But it’s managed to take a decisive lead over Boeing in the post-pandemic period, which had persistent safety problems with the 737 MAX and 787 Dreamliner. These are due to an American “MBA culture” which emphasizes financial engineering and “capital discipline” over quality control.

Elsewhere in mission critical technologies, you have companies like Dutch ASML providing the vital EUV lithography technology crucial for the manufacturing of modern semiconductors; pharmaceutical companies like BioNTech and AstraZeneca which did so much with Covid vaccines; telecommunications companies like Ericsson which the world relies on as a 5G competitor to Huawei. Alongside many other successful companies in more consumer discretionary areas, like say Louis Vuitton ($450b market cap).

Germany in particular has shown pretty substantial resilience here, even in the face of a large energy shock from Russia. Many German car manufacturers, for instance, have been moving heavily into EV production; both at the luxury end (BMW, Mercedes) as well as at the lower end (Volkswagen). And while it’s true that Germany is also facing significant demographic tailwinds — it’s managed to cope and deal with these far better than, say, Japan; which really has stagnated. Part of the difference there might lie with integration into Eastern Europe; this area seems to have been stitched together into supply chains (especially for goods like autos) in a more holistic and win-win manner compared to China and the East Asian supply chains.

European Infrastructure and Housing

The success of these European companies owes a lot to state capacity and planning initiatives to build these areas of excellence. But that government capacity is particularly evident when looking at other areas of infrastructure and housing. The Transit Cost Project has a detailed analysis of infrastructure costs around the world, and finds that many European countries build infrastructure at reasonable costs, and host competent civil servants who manage them effectively. The UK — and especially the US — build far more expensively; a complicated product of greater litigation, holdup powers by local interests, delays resulting from common law, poor procurement policies, and diminished state capacity.

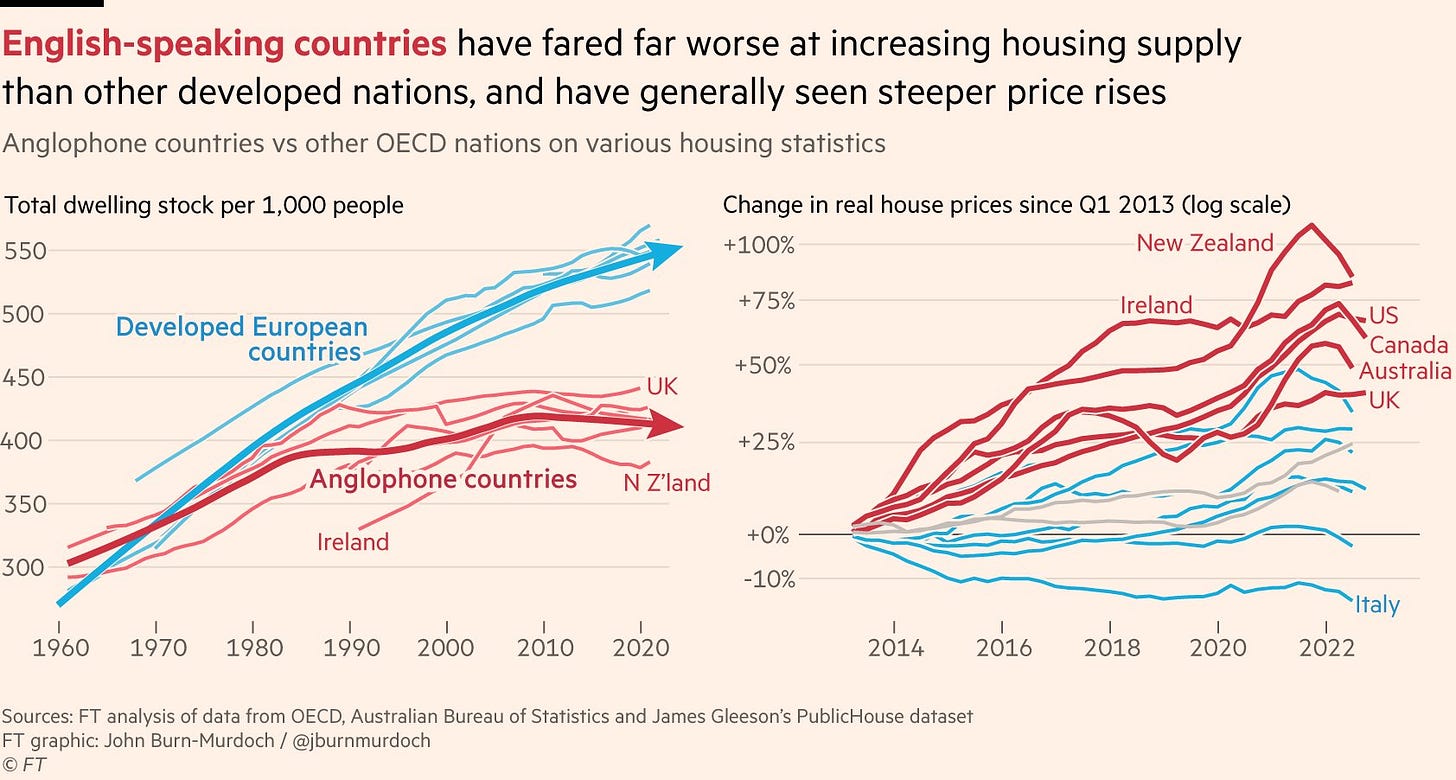

All these problems are also evident in housing, where the Anglosphere seems to lag in new housing construction, leading to rising house prices as John Burn-Murdoch has argued. The “single stair” crowd also emphasizes how European regulations and building materials allow for point access blocks built around a single stairwell, producing more environmentally friendly buildings which maximize living space and result in apartment buildings suitable for large families: who are instead leave for the suburbs in the US.

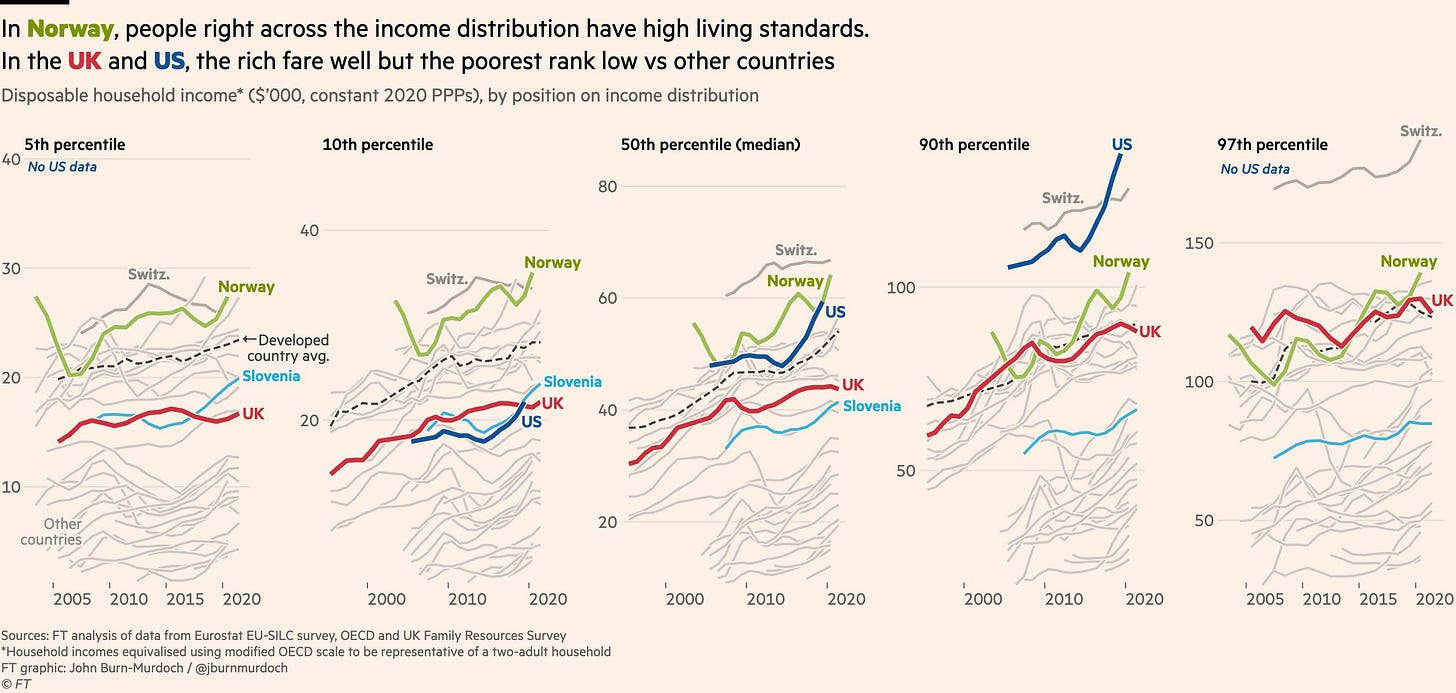

You can also see the impact of housing on household budgets. As Benjamin Wolf has emphasized — you see Austrian nationals have very high household disposable income. This reflects in part highly regulated prices (including in education, healthcare, and housing with rent controls and social housing), subsidies and support (daycare for instance), as well as greater antitrust enforcement limiting market power (as my colleague Thomas Philippon has pointed out).

When you look at commute times, you see that Americans and Continental Europeans both have sizable accessibility zones around cities, but these are achieved in different ways. Here’s a paper by Lucas Conwell, Fabian Eckert, and Mushfiq Mobarak which finds America offers better accessibility to cities and jobs by cars, while Europe has better public transit accessibility. However, European cities are more dense, so the population accessible to city centers is higher in Europe — and car dependence results in worse health and pollution externalities including worse air pollution, less physical activity, and worse health outcomes.

The overall health benefits between Europe and the US really are substantial — maybe 4-5 years of life expectancy. Chad Jones and Peter Klenow find that the welfare gap between Western Europe and the US is a lot smaller when you take these things into account (a 15% gap rather than a 33% one for income). This gap is complicated, but reflects a variety of things including drugs (especially fentanyl), gun deaths (both homicides and suicides), traffic deaths (trending up in the US, down everywhere else), and generally poor health reflecting in cardio-metabolic diseases.

Finally, you have to also take into account Europe’s redistribution and welfare state, which produces a comparable or better standard of living for the bottom 10 percent of the population relative to the US.

Europe's economic forecast? Cloudy with a chance of bailouts

I’m trying to paint a balanced picture here, adding more nuance to the usual “Europe is stagnant and bad” perspectives. Still, Europe does have its share of problems:

Regional Imbalances: France and the UK have particularly strong regional disparities; and both countries are poorer then Mississippi on average if you take out their richer capitals. Anna Stansbury, Dan Turner, and Ed Balls have a nice paper on the sources of these disparities in the UK, which have to do with low productivity in non-London cities, weak infrastructure, and concentrated public and private investment. France, by contrast, at least redistributes income a bit geographically; while Germany engages in more active place-based policies.

Stagnation in the Periphery: This graph also highlights big regional gaps across and within countries. So cities like Milan or Madrid are at least doing well — while there is this whole swathe of underperforming Europe — southern Spain, southern Italy, rustbelt northern France, Eastern (and increasingly Northern) Germany. These regions are also increasingly home to the more populist political movements.

Bruno Pellegrino and Luigi Zingales have a nice paper on Italy’s stagnation, which they blame on the failure to take advantage of tech and the ICT revolution; which itself can be blamed in poor corporate governance and weak meritocracy within Italian firms. There are probably some elements of these across underperforming regions in Europe’s periphery, which are seeing manufacturing dry up without a commensurate gain in high end services.

Innovation and Services: The failure to adopt tech isn’t just in Sicily; but there’s a huge gap in Europe’s ability to create new tech firms. Innovation, entrepreneurship, patents, etc. deeply lag American levels, even as some European regions (Scandinavia, Denmark, Estonia, the UK etc.) do better. A big source of difference lies in capital funding: “core” Europe really lacks large pension/insurance funds, which have historically seeded VC capital, which some northern European regions like Denmark do have. Europe’s privacy policies, ie GDPR, might also be a factor here.

Even in more traditional service sectors, like banking, you’re seeing the declines of many historically important firms like Deutsche Bank and Credit Suisse. As Matt Klein and Michael Pettis emphasize in Trade Wars are Class Wars, the German private sector invested 5.1 trillion euros in the two decades from 1999, but the value of those assets was 4.8 trillion euros — losing 7 percent due to investments like American subprime mortgages and Greek sovereign debt; an incredible negative alpha of 2-3 trillion euros relative to the returns other investors received.

Manufacturing/Energy Woes: While ceding much of the technological commanding heights of the economy to the US or China, Europe has shown resilience in its manufacturing firms. As Joey Politano has pointed out, the energy crisis has started to hit firms in critical energy-intensive areas like cement, chemicals, paper, etc. This shows the limits of the economic model for at least the past decade, with fiscal austerity and manufacturing substituting for consumption and expansion into services.

Other Content

I’m on a podcast with the Indicator from Planet Money on woes in commercial real estate, and quoted here in a WSJ piece on the San Francisco doom loop.

A big debate going on whether macro makes sense at all; and whether unemployment needs to go up after monetary policy tightening. This paper by John Coglianese, Maria Olsson, and Christina Patterson is nice in cleanly showing impacts of monetary policy tightening on lowering output, inflation, and raising unemployment.

Neat paper by Zach Liscow, Will Nober, and Cailin Slattery on problems with procurement raising infrastructure costs; my summary here.

Also a nice paper by Sophie Calder-Wang and Gi Heung Kim on algorithmic pricing and rent setting; my summary of that here.