Cracks in the Concrete: Banks and the Strain on Commercial Real Estate

Office Apocalypse Meets Twitter Bank Runs

Together with Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, we have a new op-ed in the Washington Post arguing we should be concerned about distress in Commercial Real Estate (CRE):

As much as $2.56 trillion in commercial property debt must be refinanced between now and 2027, and cracks in the edifice are beginning to appear, with delinquency rates on commercial mortgages rising. Trepp, a commercial property data analytics firm, reported that about 5.4 percent of office loans were in special servicing — meaning the loan payments are 60 days late — as of April. This number was about 3.4 percent just a year ago.

It all adds up to rising costs and falling revenue for many commercial properties around the country. And that is an especially grave development for regional banks that are overly exposed to the commercial real estate sector. The Federal Reserve Board’s Financial Stability Report for May shows that smaller and regional banks are estimated to hold more than 50 percent of all commercial real estate loans outstanding, including more than $600 billion in office and downtown retail commercial property. At some banks, commercial property portfolios are more than 100 percent of equity capital.

Declining property valuations will weigh heavily on these banks, which will lead them to tighten lending standards and pull back from the sector. What follows will be a vicious downward spiral, with banks cutting off credit to property owners, who are forced to turn the keys over to the banks, who then sell off those real estate assets at fire-sale prices. The implications will not be limited to the property sector, as many small and medium-size companies rely on funding from those same small and medium-size banks.

Here, I want to dig in a little bit further.

What’s the state of real estate right now?

Commercial real estate has been hit by some huge headwinds in the last few years. We have an updated draft of our “Office Apocalypse” paper (also with Vrinda Mittal), finding a 40-45% value drop for New York City office buildings, and an even larger declines in San Francisco. Retail has been hit both by a loss of commuters in urban areas, as well as the steady march of e-commerce. Even multifamily is affected, as rents have been falling a bit and a lot of new supply is coming online. This is great from a YIMBY perspective, but less so from an ownership of CRE one.

And, of course, all asset categories are being hit increase in interest rates. There is a convexity issue operating here as well: increases in interest rates are particularly impactful when coming from very low interest rate environments, as we were just in, because of the non-linear proportional increase in interest payments.

In general, I think we are seeing that a lot of “core” real estate is getting repriced. Over the last several decades, this was a great trade as investors could just hold and largely passively benefit from secular trends in lower interest rates and generally increased demand for urban life. These increasing asset valuations sustained a range of equity and debt, and now we are seeing a very rough repricing.

So what’s the evidence for these shifts?

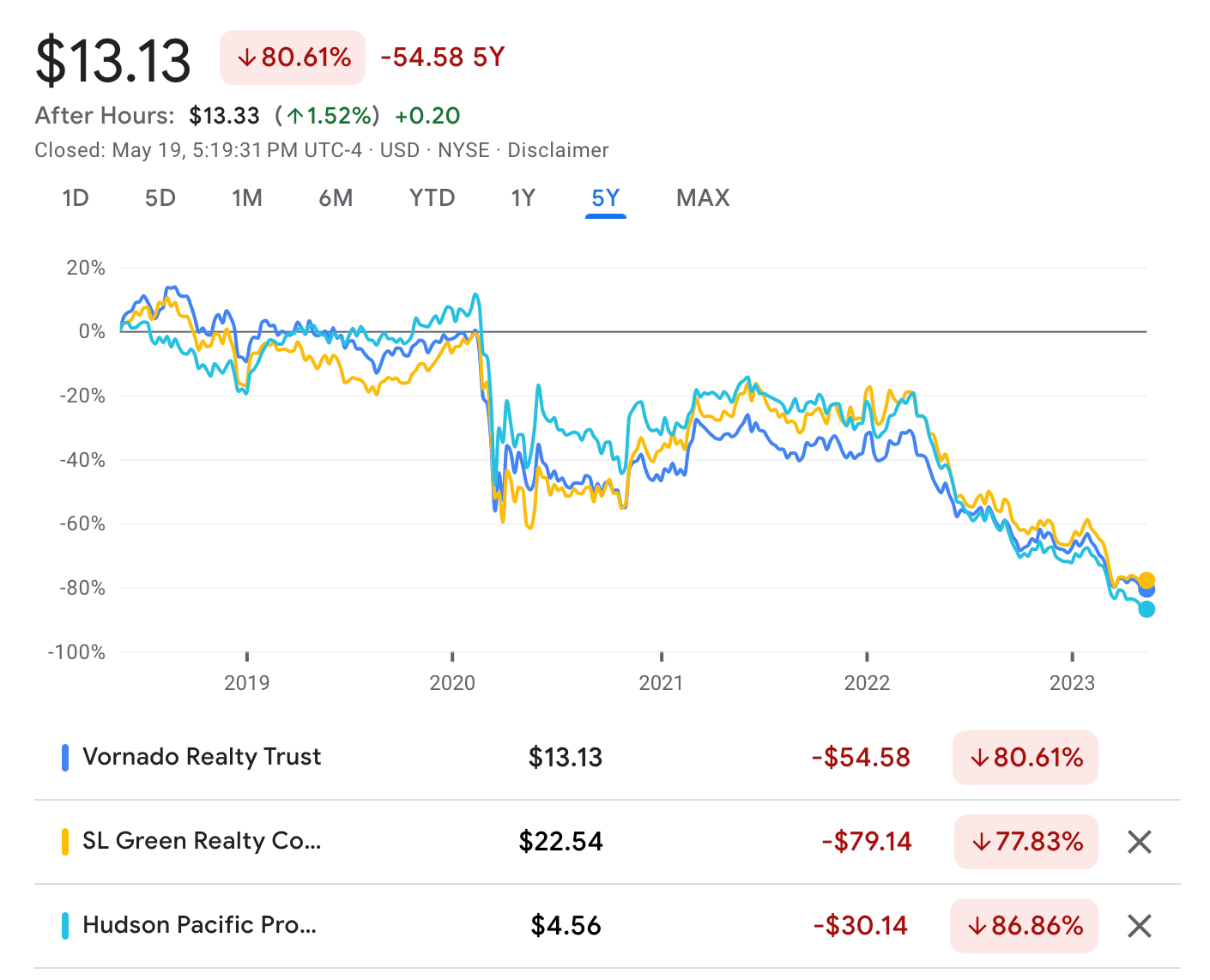

Most obviously, we can look at the equity valuations of publicly listed office REITs—three large ones here (Vornado, SL Green, and Hudson Pacific) have seen value drops of 75-90% since the beginning of the pandemic.

We can also look at the CMBX market, which is the price of default protection against securitization of commercial mortgages, which we highlight in our new paper draft:

While capital markets have priced in these trends, primary markets — where individual real estate properties trade — are still a little in denial. A few fire asset sales of San Francisco offices aside, you’re just seeing liquidity dry up and few transactions take place at these levels. Other private funds, like Blackstone’s BREIT, are trying to maintain the fiction of constant NAVs in the face of steady investor redemption pressure.

Where are banks in this?

We also looked at the exposure of investors to CRE, and found this interesting inverse-U shaped exposure across US Banks:

What’s going on here? It turns out the small and regional banks are the ones that specialize in Commercial Real Estate. The very smallest banks don’t bother, and the very largest Too-Big-to-Fail banks — the JP Morgans of the world — do surprisingly little CRE lending as a fraction of their loan books as well.

I think the logic is that the largest banks pick the most scalable asset classes to deploy lots of capital — mostly this is Agency MBS, credit cards, and large corporate lending. They actually do little lending to Main Street as a result: Commercial & Industrial loans, especially to smaller firms, and commercial real estate are the purview of these smaller banks, which have the local information and regional specialization to focus on these somewhat profitable, but harder to scale, opportunities.

The downside of this setup is that it is exactly the smaller and regional banks that do the most CRE lending, which are also facing the greatest hurdles due to deposit (especially uninsured deposit) outflow. Erica Xuewei Jiang, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, and Amit Seru have a nice paper on the joint relation between CRE risk and bank exposure.

A “CRE Doom Loop?”

Our paper highlighted the possibility of an “urban doom loop” — the idea that a decline in office values and commuting flows might have knock on consequences on urban governments more generally, contributing to even larger urban flight as services are reduced and taxes rise. This is something that happened in the deindustrialization wave of the 60s and 70s, when many city cores more than half their population, and might be a risk at play now for cities facing shocks from remote work.

Looking at the CRE in general: another concern is a “CRE Doom Loop.” While banks are not struggling due to commercial real estate concerns specifically, they are cutting back on CRE lending due to general risk considerations (ie, the Fed loan officer survey). This drying up of credit can be very damaging for CRE, which typically needs to refinance loans every 5-10 years. The combination of tight credit and higher interest rates may be enough to push some borrowers into default, which will hit aggregate credit conditions, worsening the problem.

Of course, we have seen this story before. In the 1970s and 1980s, banks were also dealing with high inflation and interest rates, and tried to grow out of their problems by moving more into commercial real estate. Downturns in that sector, including in the 1980s and especially after the 1990 recession, led to large CRE losses and substantial bank distress. We remember 2008 today mostly in light of the credit cycle doom loops that happened in residential real estate, but it was also a rough period for commercial real estate as well. CRE is basically a cyclic asset class that will be very vulnerable to any future downturn.

Zombie Buildings and Financial Meltdown

Policymakers here I think have a tradeoff between zombie buildings and financial meltdown.

If you intervene heavily into the market — encourage forbearance, extend-and-pretend, and so forth; you’re going to limit financial contagion, but probably also limit the extent of necessary asset redeployment that needs to happen. I think this is different from previous cycles in the extent to which CRE assets probably need to get redeployed and altered in their use. It’s a lot easier, as an office owner, to continue to demand well-above market office rents, and just deal with a declining occupancy base, and basically stick around as a “zombie” building if you can evergreen your lending.

The alternative is to force broader asset resolution and asset writedowns: but potentially at the cost of exactly that broader financial damage.

It’s a tricky balance. One option we point to — and are working on more work to develop — is to try to target funds towards ensuring that necessary asset redeployment (for instance, converting office buildings into multifamily) take place.

Other Content

I did a podcast with Reihan Salam on breaking the urban doom loop:

Two pretty cheap ways to drastically improve student performance: reduce pollution from school buses, and use evidence-based phonics reading methods, which are raising test scores in the UK and Deep American South.

Are smartphones and social media responsible for declining teenage mental health? Here’s a study based on rollout of broadband in Italy; and a nice discussion between Ezra Klein and Jean Twenge.

College graduates increasingly leaving expensive coastal cities [NYT].

A paper by Sophie Calder-Wang and Gi Kim on how algorithmic pricing is raising rents in multifamily; perhaps due to algorithmic collusion, or helping owners set more responsive prices.

How to succeed in academia, by Lasse Pedersen.

Growing Like India: India has a service-led growth pattern, which has resulted in development mostly skewed towards high-income urban dwellers.

Ozempic is a general purpose drug against impulsivity. This is very valuable since many of the problems we face — obesity most directly, but also social media, drugs, gambling, alcohol, etc. — are products of impulsivity and a general drain of self-control. There’s a good demonstration of this in a paper by Archana Dang which directly connects undersaving and obesity as joint consequences of an underlying impulsive behavioral trait.