The Biden infrastructure plan is a key Legislative priority at the moment. There is a surprising level of bipartisan consensus that investment here is essential to maintain productivity and international competitiveness; but disagreement on who should pay for it.

The Republican view is that transportation should be paid for by user fees and gas taxes, which charge people who will use infrastructure. Biden’s argument is that this goes against his pledge not to hike taxes for those who earn less than $400k; and so the preference is instead to use deficit funding or tax corporations. More broadly, there is a lot of interest by progressives in funding social programs by taxing financial wealth rather than through other tax instruments like the VAT.

Tax the Wealth of People who Benefit

There is a third option here, which I explore in a new Manhattan Institute brief on Value Capture. This builds on my work with Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh and Constantine Kontokosta on the 2nd Avenue Subway:

We find that real-estate prices started to increase after construction began on the Second Avenue project in 2007, even before completion of the project in 2017. Relative to the period prior to subway construction, real-estate prices in areas served by the subway increased by about 8% more than in other areas of the Upper East Side. These estimates suggest substantial demand for properties in the area served by the new transit expansion, as well as large value creation from the subway. Aggregating across the region, we find that the subway expansion increased total real-estate prices by as much as $5.8 billion—enough to pay for the extraordinary $4.5 billion cost of construction.

However, we find that the city did not recoup the bulk of that cost of construction. While the existing property-tax system will result in the city taxing some of the windfall gains from higher values, the resulting revenue gain falls far short of the total cost. We find that the present value of the increase in future property-tax revenues amounts to just $1.78 billion. This means that even though the subway project generated enough real-estate value to pay for itself, the bulk of this simply accrued to private landowners with preexisting ownership stakes. The city government faces a substantial shortfall in revenue to pay for the project. These costs were instead borne by federal and local taxpayers.

The basic issue is that infrastructure improvements increase land value, and so provide windfall gains to landowners who just happen to own land in the vicinity of transit stops. Value Capture is the idea that — because infrastructure benefits are capitalized into property taxes — infrastructure projects can be financed by levying higher property taxes.

Ways to Value Capture

There are a few ways to do this:

Tax the incremental uplift in value through targeted property taxes. This is something being done, for example, with Crossrail in London — the new East-West line spanning the city.

Accommodate increased real estate demand by selling upzoning rights in areas around transit stops. That’s something New York City has done with the Hudson Yards project. This was a new development in Midtown, in which development rights were sold as a way to partially finance the extension of a subway line to the neighborhood. Chris Elmendorf and Darien Shanske refer to as this strategy as “Auctioning the Upzone” and advocate explicit auctions. São Paulo does an interesting version of this as well, by selling development rights in specific areas that are targeted to development in those places.

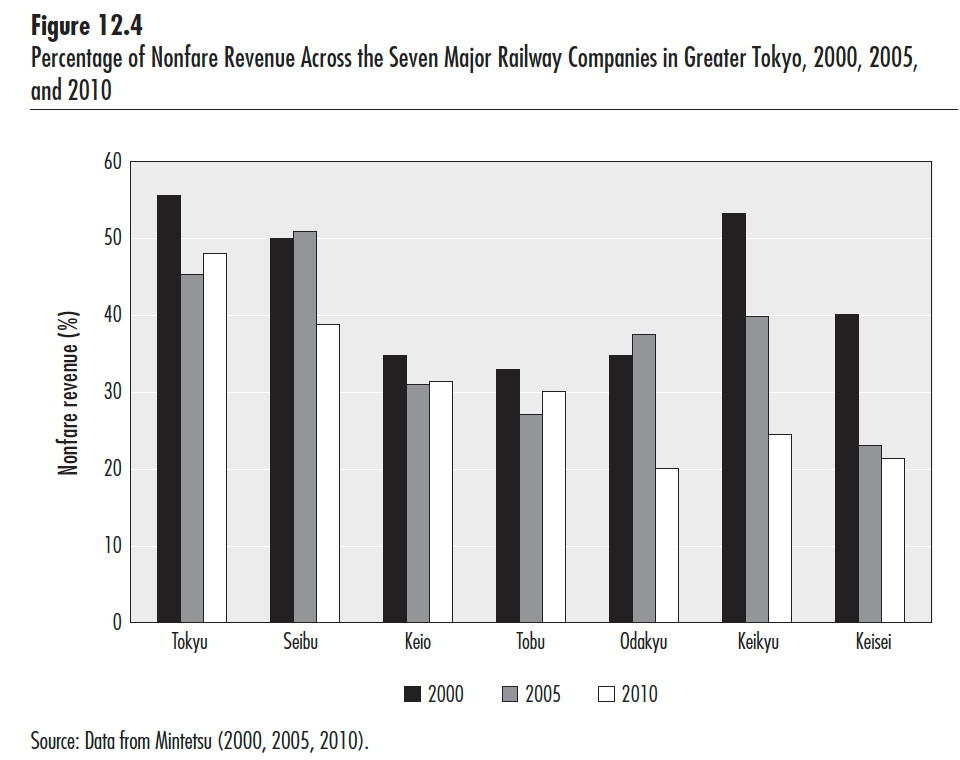

Internalize the complementarity between infrastructure and real estate. This is something that was once very common in the US — the whole country was once blanketed by railroads and streetcar lines which doubled as real estate development companies. The bulk of the New York City subways, for example, were built by private companies. These firms were able to internalize the real estate uplift in the area of transit lines by developing themselves or selling off those development rights. It’s a model that survives today with the transit companies in Tokyo and Hong Kong. These companies, some of which are even privately listed, earn considerable revenue from “nonfare” sources — which include real estate developments around stations.

The takeaway from all of this is that we can better build and finance essential urban infrastructure by recognizing the links between transit and land development. Finding tools to tax property owners, or otherwise unlock new development in areas around transit stops, opens up new financing sources to pay for projects. It’s a little like a user cost, in that it targets people who are most likely to benefit. But it also taxes wealth, and so is more progressive than a gas tax or user charge; and limits the otherwise windfall gains of infrastructure projects heading existing land owners.

The other thing to realize is that we already extract value from new projects, but often in less effective ways. In New York, for example, we have Mandatory Inclusionary Housing — zoning tools which push developers to create affordable units in exchange for permission to create new market-rate units. Getting the legal authority right here is tricky, but it’s generally preferable to extract value in the form of fungible cash, rather than specific housing units which only benefit a handful of residents lucky enough to qualify for that affordable housing.

I think there are two serious objections to value capture as an infrastructure strategy. First, the critical problem for many US projects isn’t the financing part so much as the cost. The 2nd Avenue Subway in New York itself kickstarted a lot of these discussions as it emerged that the city builds subway lines for something on the order of 10x the international price. So clearly bringing the cost down is a major priority here that needs to happen in parallel with any funding change. Second, value capture ultimately represents an increase to the cost of doing real estate business; and like any tax might be expected to lower housing costs. People who are particularly concerned about this may prefer the upzoning solutions, rather than the increased levies, to avoid clogging housing production even further.

Impact of Covid-19 in India

Switching gears here a bit — I have a new paper out with Anup Malani and Bartek Woda examining the impact of Covid-19 on India in the first wave in 2020. We use the CMIE household survey data, which turns out to be an interesting dataset to explore the household level impacts of this pandemic.

India is an interesting place to study the impact of the pandemic because the initial wave of lockdowns was extremely severe — some of the harshest lockdowns in the world — and there was relatively little public insurance and stimulus to buffer the shock. So while United States was able to bounce back remarkably quickly (if unevenly) given the extraordinary levels of monetary and fiscal policy support — what happens in country which has to sustain itself largely on the basis of private insurance alone?

We see that household income takes a huge hit. Consumption falls quite a bit as well, but not as much — suggesting that people were able to buffer the shock to consumption despite limited public assistance.

We do some traditional Townsend-Cochrane style tests of consumption smoothing, contrasting the consumption change (log c) against the shocks to income (M):

We can definitely reject complete risk sharing here — shocks to income do impact household consumption — but the magnitude of the violation is somewhat small, and does not really change with Covid. Interestingly, household insurance works a little better in rural areas — where Indians are typically tapped into caste networks which provide insurance as well.

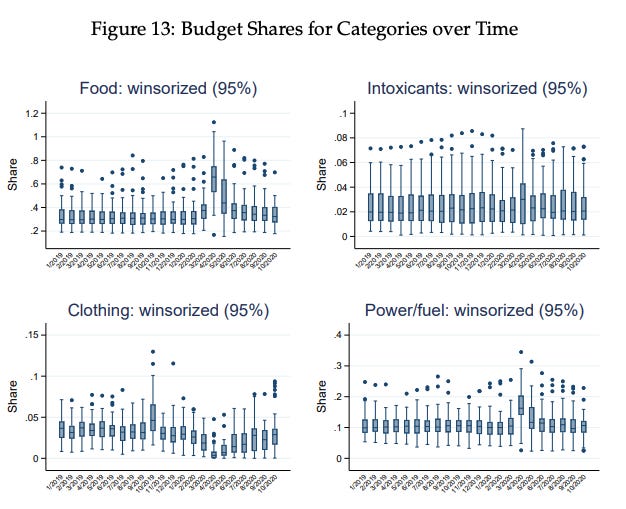

The magnitude of this consumption insurance protection really changes across consumption categories. People really increased the share of consumption that they devote towards food, while cutting back on other non-essential consumption categories like clothing or alcohol. So food consumption was prioritized in the initial severe lockdown period.

Another protective tool people used was occupation switching. Again, it’s interesting to draw the contrast to the US, where people are relatively well insured against shocks through programs like unemployment insurance. Relatively few people seem to have switched across sectors, instead relying a lot on public assistance. In India, by contrast, it looks like people are switching occupations much more often at baseline — and were particularly likely to do so in the pandemic.

This kind of mass occupation switching — much of it to categories of low-skilled work which could accommodate more workers such as agriculture — sort of replaces unemployment insurance in a developing country like India. But this strategy has costs of its own, because workers in destination sectors (like those agricultural workers) now have to compete for labor against a larger pool of entering workers.

We are planning to dig into these mechanisms in more detail in future work — as well as look into the second wave in India that happened earlier this year. But these are our preliminary findings, which hopefully shed some light on what happened over an eventful year. The ultimate goal here is to use the huge shock of Covid to better understand what institutions and protective tools households use to shelter themselves, and the value of these tools of private insurance.