How Finance Killed Democracy

How deflation and capital extraction boosted the 60/40 Portfolio. Plus: Expensive Infrastructure Explained

The Long-Term Decline in Rates and Asset Returns

On Odd Lots, Paul McCulley makes the provocative claim:

Unambiguously, we’ve had 40 years of disinflation, and that’s because we’ve shifted power in our economy, both domestically and globally, from labor to capital… We’ve had a 40-year tailwind of falling real interest rates, which will by definition increase the market value of all income streams. That’s what capitalism is all about: Ownership claims on income streams. It’s been an incredible bull run on the valuation of financial assets. And I certainly hope, as a citizen, that is not repeated… If it [the 60/40 portfolio] were to work on a secular basis for five years, 10 years, 20 years, then we have unambiguously failed as a democracy.

I think this is basically true, and digging into why is really important.

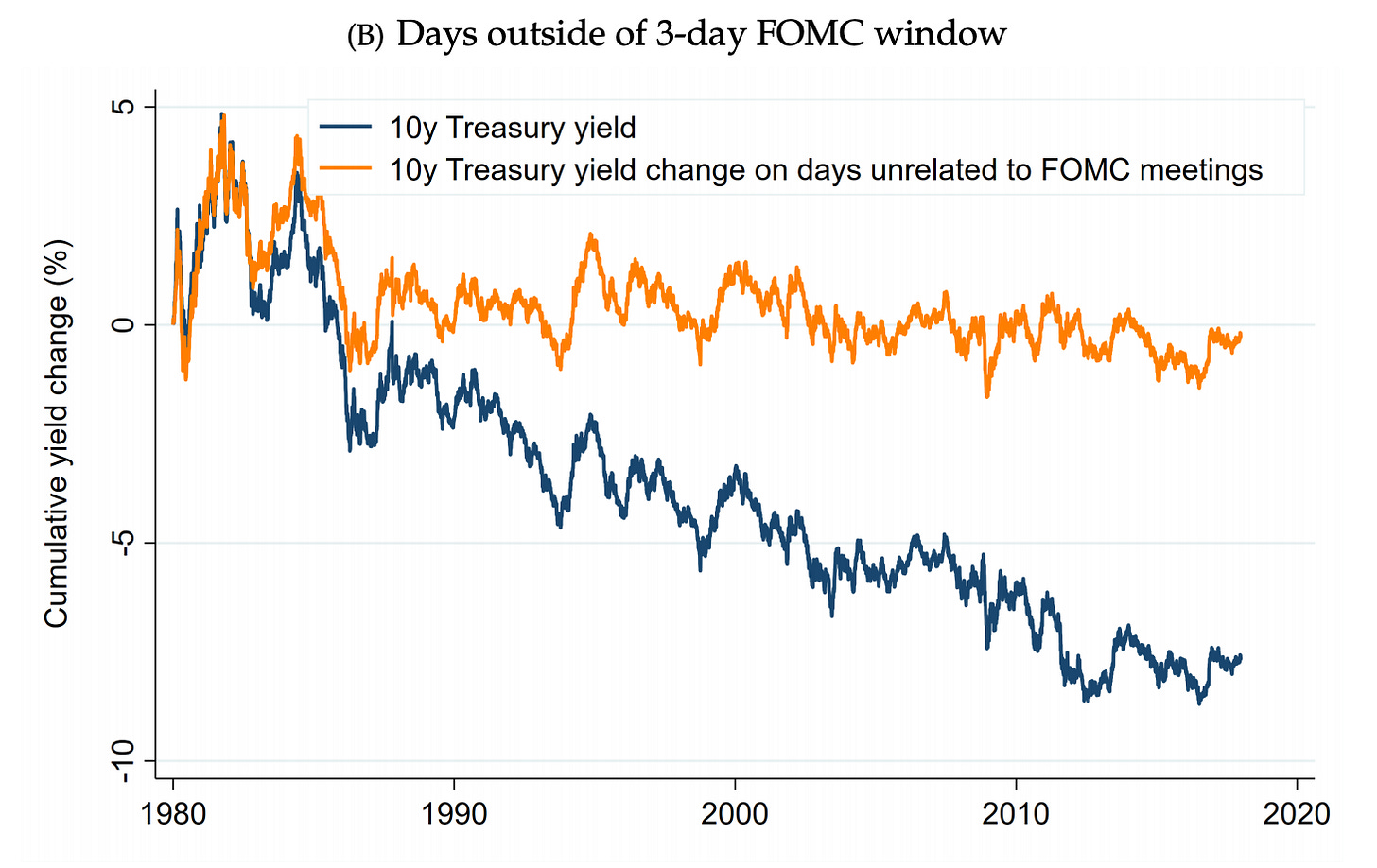

First, let’s start with the declining interest rate part. There is a really great paper on this by Sebastian Hillenbrand, one of our NYU Stern PhD students (watch out for him on the job market!). He finds that 100% of the decline in long-term interest rate over the past 40 years has happened around 3-day windows of FOMC meetings.

Now, what’s not surprising here is that prices move around FOMC meeting periods when interest rates get decided. We have papers on pre-FOMC drift; and papers on post-FOMC drift. Long-term bond rates consist of expected future short-rates, plus a term premium. So to the extent that policy announcements forecast future short-rates, it makes sense that things like 10-year yields would be affected.

What’s weird is that you also expect information to come out all the time, on non-FOMC days, which would also be relevant for monetary policy. News about demographics, secular stagnation, savings gluts—all this other stuff that we think is behind the long-term decline in long-term rates. And all of this news has zero aggregate impact on long-term bond rates; outside of that 3-day FOMC window—it all just washes out on net.

Now, this large shock in interest rates should also have an effect on equity, as we discount future earnings (particularly far out earnings) by less. And sure enough, the bulk of valuation changes in equity, over this period, have also happened around FOMC days:

Now why this has happens is a great question. A plausible story I think is that we keep learning, with every FOMC meeting, that the Fed put is even larger than we thought—so we keep ratcheting rates down further which has good consequences for bonds, stocks, and ultimately the canonical 60/40 stock/bond portfolio. It could be that this was a good or bad idea. But you can only get valuation shock once. Expected returns, going forward, won’t have the benefit of this disinflationary force.

The Shareholder Revolution and the Fate of Democracy

So in addition to this Fed-engineered shock to interest rates, we have also had this wrenching reallocation of corporate form. Intellectually, we had this Jensen and Meckling idea that the central problem of corporate governance is the agency conflict between managers and shareholders—and this is best managed by empowering the “owners” of the firm to force managers to add value for shareholders.

Dan Greenwald, Martin Lettau, and Sydney Ludvigson show that from 1989-2017, a large chunk of shareholder gains were generated by redistribution of rents towards equity-holders. I think the way to think about this change is that we drastically shifted the balance of power in corporate governance. This happened in public markets through stronger boards and management that was better compensated through equity; and involved activist hedge funds and private equity firms who hyper-charged the market for corporate control to change that management if they weren’t willing to go along with the shareholder-driven model. Corporations trimmed out the fat, and paid out way more to equity, boosting stock returns over this period.

Now, another way to think about the split between labor and capital here comes from Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman, and I borrow from Matt Rognlie’s great discussion of this paper. K-N introduce this concept called factorless income. Basically, we take corporate income, and subtract out the share that goes to workers. Then, we account for capital in the form of a user cost—basically the rental rate of capital based on interest rates. We get a sizable wedge that’s left over, that can’t plausibly going to either workers or can be accounted for by traditional interest rates.

Basically, there is some sort of financial “dark matter” showing up here—a residual in aggregate income that survives after allocating to labor and capital. Rognlie offers a great possible explanation for this residual:

My guess is that there is a deeper lack of transmission between financial-market rates of return and the real rates used to make investment decisions. To some extent, this is already known: it is well-established that corporate hurdle rates are usually far above stock or bond returns. Could this gap expand or contract over time, leading to variation in factorless income? Perhaps the rise of shareholder payouts and corporate “capital discipline” over the last few decades has propped up the required return on capital, even in the face of declining financial market returns. This hypothesis sounds similar to markups, but there is an important distinction: markups distort overall production, while high hurdle rates distort capital as an input to production.

So here is a simple way to think about it. A private equity firm buys out some company. Even though prevailing bond rates are pretty low (remember: the first part of this newsletter), PE firms typically have pretty high expected rates of return (they are going to want to see, say, a 15% IRRs or maybe a 50% increase in the total cash invested). In order to meet these high expected rates of return—firms may cut back on some production; economize further on resources, etc. Firms are basically squeezed dry to maximize returns for shareholders.

Additional evidence for this mechanism comes from Simon Jäger, Benjamin Schoefer, and Jörg Heining in a nice paper on the effects of codetermination—what happens when you increase labor participation on boards (also similar to what Oren Cass has been advocating for). Firms with greater shared governance do pay out 0.4%-2.3% higher wages. But the main effect is that increased labor representation actually increases capital investment, which goes up a bunch. This is consistent with a story in which capitalist control reduces investment in a way that lowers the net present value, but raises the IRR or the yield. This is what you expect to see in any production function with decreasing returns to scale. Operating everything in a sort of capital light manner allows you to get higher returns per dollar invested, even if it doesn’t maximize total output.

If you add all of this up, you get a pretty depressing story for democracy. We achieved a massive one-time boost to stock and bond returns through two mechanisms:

Fed-engineered deflation, which led to a dramatic decline in long-term interest rates (read: a large increase in bond prices), and a large increase in the valuation of stocks and other assets.

An economy-wide reallocation of rents as we shifted the balance of control towards capital, resulting in persistently low investment and high equity returns.

These trends were great for asset returns, but involved large unequal transfers of wealth and we are still grappling with the political consequences. Doing this kind of thing again in the future seems really politically unsustainable, hence the failure of democracy if this were to continue.

tl;dr — Paul McCulley was right.

Why Infrastructure Costs So Much

Okay I don’t want to sound too much like a socialist and lose my Economist card. So let’s talk about why regulations and local participatory democracy are why we can’t have nice things (specifically, infrastructure or cheap housing).

There is a great paper on this by Leah Brooks and Zachary Liscow, and a nice accompanying podcast discussion in Densely Speaking featuring Jeff Lin, Greg Shill, and Jenny Schuetz. Here’s a key finding: the cost of interstate highway construction started to go way up around 1970, without obvious “fundamental” explanations in terms of labor or construction cost.

These increases in costs can be “accounted” for in some sense by local rises in income—but only after 1970. This is a notable break point, of course, in many macro time series. So what happened then which was so relevant for our ability to get cheap infrastructure?

First, I think the really important backdrop here was the urban clearance movement, which led to the demolition of as many as one in seventeen housing units in order to make way for highways and urban renewal projects. This was the age of Robert Moses, and it led to a countervailing opposition—the Jane Jacobs of the world. The pendulum between central forces pushing for infrastructure, and plucky neighborhood forces blocking these efforts has since swung way too far towards local NIMByism. This happened through three major changes starting around 1970:

NEPA, the National Environment Protection Act, which introduced environmental impact reviews.

Judicial Review, in the form of Acts such as Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, which increased citizen ability to sue over projects.

The creation of citizen organizations to block transportation projects. In addition to purely non-profit and privately led organizations, this also includes an entire body of hyper-local government in the form of local Transportation Community Boards which popped up around this time.

The cumulative effect of these changes was to empower citizen voice to block and reshape infrastructure projects in ways that led to drastically higher costs, particularly in areas with wealthier and more mobilized citizenry.

Now, this shift away from the Robert Moses model did have some good aspects. We probably did build too many freeways, particularly through urban centers as Jeff Lin and Jeffrey Brinkman discuss. However, they also find that the resulting freeway protests pushed highway construction even further into low-income and minority areas, which had less political power.

Ultimately, what’s going on here I think is a breakdown of Coasian bargaining. Ideally, we would like to account for externalities of infrastructure projects and mitigate them in various ways or else compensate the losers. So avoiding some highway projects entirely, and constructing the projects we do fund with sound barriers or even putting them underground makes sense.

The problem is that our planning process is poorly oriented around addressing these externalities directly. Local residents—who do have legitimate concerns around these externalities—are able to hold up these projects through a variety of stalling mechanisms at their disposal. The resulting delays add even further to the costs, resulting in unaffordable infrastructure.

Now, it’s hard for me to get too upset about these problems for highway projects. I put high weight on the externalities resulting from highways—auto deaths, noise, pollution, etc.—so I do have sympathies for a political process that is heavily weighted around addressing them. The problem is that the same process and cost issues doom the construction process for other essential public infrastructure and residential construction.

Here for instance you can see the results of a great new data initiative by Eric Goldwyn, Alon Levy, and Elif Ensari on urban rail infrastructure projects. These are the most expensive urban rail projects in the world, which are mostly in America or other Anglophone countries.

Now, I think the benefit of these projects can be massive. In a paper with Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh and Constantine Kontokosta, we find that the 2nd Ave Subway Extension raised real estate prices by 5-10% in the area around station stops—possibly enough to pay for the the expansion alone, despite the high costs. The benefits of improved commuting and urban agglomerations, are so large that they even justify these bloated construction expenses, at least in hyper-dense NYC. But lowering these construction costs would help justify transit expansions in many more areas.

The same problem is true in real estate. Here, for instance, you can see new private housing authorized per capita. We haven’t hit the construction highs that we did in the 1970s, and since the 2008 financial crisis have barely even hit the minimum from the period over the 1990s-2000s.

What’s going on with infrastructure costs is bad—but what happened with real estate costs is a national catastrophe. Over time, we have introduced numerous veto points in the residential construction process. These allow politically engaged NIMBYs to hold up and block new construction, or else ensure it is prohibitively expensive. To be sure, I do think in many cases NIMBYs have reasonable objections around construction—the hyperlocal externalities of new building in terms of noise, construction, and parking.

But these concerns are best met through minimally tailored design changes or else Coasian side-transfers, not a blank veto over new housing or a generic right to design projects by committee. We end up with a system of property rights that extends way over our own property lines to block anything nearby in ways that that essentially destroy our ability as a society to address affordable housing needs.

As a YIMBY, I’m hopeful we can try to reverse local control over housing and transit and push them up to the city or state level, where planners are better able to balance both costs and benefits of new construction. As a remote work booster, I’m also optimistic about changes in work patterns that disperse population more evenly across the country, so that optimizing our transit and housing in dense urban areas is less critical. But to do so we need to understand the root causes of our inability to construct new housing and infrastructure, and reassess how we think of the Robert Moses v. Jane Jacobs dynamic. Sometimes, we need a little more Robert Moses—just applied to the types of projects that benefit everyone.

Other Links

A good discussion by Benn Eifert breaking down the tech bubble story. You don’t see enough trading in equity by retail investors in Robinhood to make a huge dent on prices. But—it looks like retail investors are also buying up a lot of call options and making highly levered bets on tech stocks. This, in turn, forces dealers to delta-hedge this exposure by buying tech stocks themselves. The story seems a little odd, but is plausible given 1) Higher purchase premium on call options, 2) Higher implied volatility in tech stocks based on options, 3) A lot higher option volume trading, and 4) Tech stocks going higher at the same time as volatility in the market going up. Let’s just keep sports betting closed for the time being so these retail investors keep boosting prices.

Salim Furth is critical of “Missing Middle” housing. I think he makes a good point that housing reform seems most successful when it allows existing home owners to increase the value of their properties, without further disruptive change. So things like ADUs have been very successful; changing parking requirements and lot minimums may be very helpful as well in creating more walkable and livable neighborhoods, even within the single-family zoning framework.

Interesting new report on climate change finance.

Great report on why we have too few physicians. I used to think there was some sort of AMA cartel limiting supply. It turns out that we have systematically underestimated our physician needs, and so wound up really undersupplying the market.

Interesting report on why Karachi has such bad drainage.

Here’s the best explanation I’ve seen so far on why California has been having so many wildfires. It seems we went too long without allowing for periodic bush fires, so things built up until we had much more catastrophic waves. Zoning is, I think, also relevant here. Because we don’t accommodate enough housing in California’s coastline, people wind up building further into the forests. And local residents don’t look too kindly on controlled fires locally.

We’re seeing a surprisingly quick labor market recovery, according to Matt Klein.

NASA is paying for Moon rocks even though it doesn’t really need any—an interesting way to help build the market in interstellar travel and mining.

He gave us one hundred and fifty years, all we gotta do is re-learn what he taught us….

it seems like reason 2 does the heavy lifting, insofar as it made the disinflation possible without spectacular fed actions. the shareholders lower investment spending and wages, and their propensity to consume their extracted income is lower. so you would expect 2 to produce low real interest rates. the fact these real interest rates coincided with low inflation was the fed’s choice, but I guess it made it possible to achieve low inflation without doing anything that would make people mad at them.