Markets in Everything

Like many economists, I’m pretty interested in political betting markets for both healthy and unhealthy reasons. The unhealthy reason, of course, is refreshing an infrequently updated set of numbers provides a hit of sweet, sweet dopamine.

But there are some good reasons to care about prediction markets too. With contracts typically paying off $1 in the realization of a particular state; they approximate Arrow-Debreu securities across a lot of interesting outcomes. There is substantial money invested in these markets, particularly if you look at venues like Betfair. Markets clearly aggregate information at critical moments—after the first Trump-Biden debate for instance, when they showed a clear Biden lead—helping us make sense of real-time events in advance of polls. So it would be great if we could use them as general purpose wisdom of the crowd aggregators, and there is some research that bears this out.

At the same time—these markets are host to a ton of transaction costs and other problems. They tend to attract a partisan clientele which may be invested in particular outcomes, which may even use markets to try to manipulate the outcomes. “Long-shot bias” is a huge problem—there just isn’t enough money in betting against unlikely outcomes, so unlikely outcomes are badly priced. You worry about the difference between the risk neutral and physical probability measures—if people are trying to hedge against particular states of the world, betting market prices will also bake in that risk aversion. All of this, of course, applies to real world markets as well. And so understanding market functioning in political betting contexts is an important test case of broader principles of market efficiency.

Judging Election Forecasts

Nate Silver takes a dim view of markets, so let’s see how his model did in comparison to betting markets. First, let’s just look at the overall win/loss number. Here, I’m plotting the 538 estimated Democrat share of the two-party vote in each state against the PredictIt market prediction for Democrats that state, as of Nov 2. The ultimate outcome for the state is reflected in a red/blue color.

There are three key states that differed on the lower right quadrant—NC, FL, GA—all of which 538 thought would go to Democrats, and PredictIt thought would go to Republicans. Let’s call that 2/3 for betting markets.

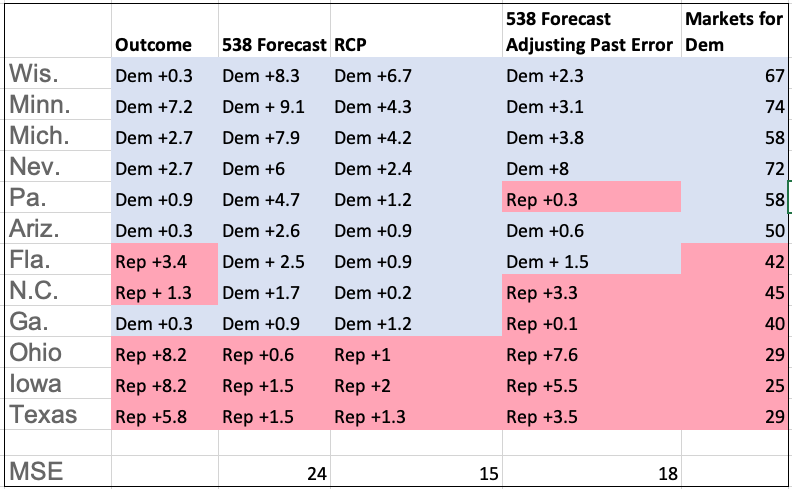

You also see betting markets are generally more Republican-leaning in ways that were ultimately born out—538 thinks TX, OH, IA are basically tossups, while betting markets (correctly) assigned these as deep red states. To look at this more formally, let’s compare the betting market forecast for each state, along with the 538 forecast, as well as the realized outcome:

Betting markets are pretty well calibrated—state markets that have an estimate of 50% are, in fact, tossups in the election. 538 is at least 20 points off—if 538 says that a state has a ~74% chance of going for Democrats, it really is a tossup.

So what are betting markets doing differently?

First, they may be taking into account past polling error. Here, I’m plotting the bias between 538 and betting markets; compared against the past 2016 polling error. There is a slight upward relationship; suggesting that markets are a little skeptical of Democrat polling leads in states where polls had missed previously.

Betting markets are also weighing different sets of polls. Here, I’m comparing the 538 - betting market bias against the bias when comparing 538 against the Real Clear Politics poll averages.

When I saw this trend pre-election, I thought this did not look great for betting markets. TheRCP and 538 averages really started to diverge this election, as RCP kept in more Trump-leaning pollsters like Trafalgar, in ways that were criticized by folks like Nate Cohn. In the end, though, incorporating 1) past polling errors; 2) a different sample base of pollsters; and 3) additional non-poll information allowed betting markets to do pretty well.

To see that, let’s focus on some of the key swing states again and compare model accuracy. The 538 polling average does not do great here, with really substantial misses on the order of 7-8 points consistently in favor of Democrats in some key states like WI, OH, IA. The RCP model averages do a lot better, and get you consistently closer to the outcome with lower mean-squared error. In fact, just taking the 538 average and adjusting each state’s model error gets you a better model fit (though not as good as RCP’s average).

Some of the betting market estimates for the states look like efficient combinations of adjustments for past polling error and the RCP average. Across the Upper Midwest (MI, WI, PA)—betting markets saw tight races with slight Democrat advantages, consistent with either the lower RCP averages or past polling error here. In states like Ohio, Iowa, and Texas, betting markets saw strong Republican advantages despite close to even polling across 538 and RCP.

However, it doesn’t look like markets are just looking at RCP or adjusting for past bias. Florida is a good example—either the RCP average or past polling bias on 538 would result in a Democrat advantage, but betting markets are reading the state as Republican. In NC as well, betting markets were more skeptical of the Democrat lead than RCP alone in the correct direction. Georgia would again be the miss, where betting markets saw a slight Republican lean but the state turned out to be a wash.

So overall it looks like betting markets did a reasonably good job at providing well-calibrated estimates that efficiently combined information better than 538. I have a few lingering concerns here. It’s possible that the pool of investors was just unusually pro-Trump (after winning their contracts back in 2016, they have more money to play around with); going forward they may be pro-Biden. Pollsters like Trafalgar are very opaque in their methodology, and may not be adding very much signal relative to just a generic Republican boost to some polls. Still, in a world in which polls are regularly off by a bunch it seems like prediction markets are bringing some useful information and we can look at them.

What Happened With Polls?

David Shor has one idea that coronavirus itself started to skew polling, as Democrats start staying at home more became started to be very active in taking surveys.

This may be part of what’s going on; but I’m not sure I see how it explains all of the geographic aspect of polling bias. It turns out, for instance, that polls were off in 2020 generally the same places they were off in 2016; even after things like education weighting have been adjusted.

What makes more sense to me is another idea that David Shor and Sean Trende have mentioned — some geographic variation in low-trust voters who don’t answer polls. Particularly in Upper Midwestern states, the types of marginal voters hard to reach in polls appear to favor Trump; while marginal voters in places like Arizona tend to support Democrats. If it were just a liberal answering polls story, you might expect Arizona or Nevada liberals to also be active in picking up the phone. But polls in Nevada, for instance, tended to under estimate Democrats. So it seems to be about the specific set of low-trust people who are reluctant to answer polls, which has a partisan bias varying across area. This hard to measure trust variable turns out to be a challenging issue to fix just through poll sample weighting.

The COVID Realignment

Before the election, we talked about how it appeared that Republicans were solidifying gains in an economic message; resulting in gains among non-white voters. So far it seems this trend has really borne out in the election, with some of the biggest news being the Republican swings in heavily Hispanic places like Miami and the Rio Grande Valley. News reports seem to emphasize that Republican messaging on the economy and lockdowns seem to resonate across a racially diverse audience.

Exit polls, of course, can’t work that well if even polls aren’t great. But the magnitude of the responses in some of these exit poll questions is too large to be accounted for by polling bias. It seems plausible to me that voters perceive Democrats as the party better suited to combat the pandemic; Republicans as the party that wants to open up and will grow the economy; and have sorted themselves accordingly. My guess is that this underlying partisan disagreement will make addressing coronavirus more challenging in the months to come.

Addendum

Otis Reid asks for the following picture. This highlights that 1) 538 is good when it comes to results being correlated with the outcome; 2) RCP/Trafalgar are good at being unbiased, but the correlation is worse. This suggests that RCP is not necessarily a better polling aggregator—they just have a R-leaning bias which turned out to be accurate. Betting markets look good here, however, as they have the unbiasedness property of RCP while being even more correlated with the outcome than 538.

538, polls, and betting markets aren't competitors and you shouldn't frame it as such. Polls-> 538 -> markets are a stack. They are built on top of each other and add additional information at each layer. Each layer *should* be better than the lower levels. If you want to compare, you should compare value-add. I suspect the markets are the least valuable. And calibration across states in one election is not sufficient for any judgment due to correlated errors across states. Markets would be very very bad without polls or models.

Two key points i would add: 1) you are only looking at ex-post calibration for a single election with a strong common component (GOP outperformed polls). In other elections (eg 2012) Dems outpeformed polls. 538 has done analysis across all their predictions in many cycles and shown they are at least unconditionally well calibrated. 2) I've bet on differences between 538 and betting markets in 538s direction for three straight cycles and its been profitable each time. Eg 538 was more bullish on Trump than betting markets in 16. Small sample of course but still.