Geographic Variation in Opportunity

When I was in graduate school, I was really surprised to see work by Raj Chetty and co-authors on the stark geographic variation in access to opportunity around the country. A particularly striking fact for me was the fact that North Carolina — the state I grew up in — scored particularly badly in intergenerational mobility: the odds that a low-income child who grew up in the area would ultimately grow up rich. Charlotte, for instance, winds up being dead last in economic opportunity, in contrast to its status as a quickly growing Sunbelt hub home to many corporate headquarters.

So what’s going on here? Why do different parts of the country offer such strongly differing prospects for children who grow up there, and why is this only weakly associated with other economic factors like job growth?

Chetty and co-authors find that exposure to crime and different family structure — the share of families that have one parent — are really strong predictors of worse local opportunity. James Heckman has a nice discussion of Chetty’s work that also highlights the possibility that children’s exposure to incarceration at the household level might result in these persistent differences in access to opportunity. He mentions in particular some sociological work using long-running surveys that span multiple generations, which find that exposure to incarceration tends to impact the whole community and persist intergenerationally.

How to Write a Paper on This

So I was really struck by these associations, and started in grad school to think about the connections between incarceration and opportunity on this with some other students. This turns out to be a really hard question to study — we tried to get data connecting criminal justice and educational records in different jurisdictions around the country, and wound up sending hundreds of emails. We had collaborations that almost went through but fell through at the end. We submitted one grant, which was rejected in the end in part because a reviewer really objected to a descriptive statistic of “2.4 million” in the introduction, which they felt really should have been “2.3 million.”

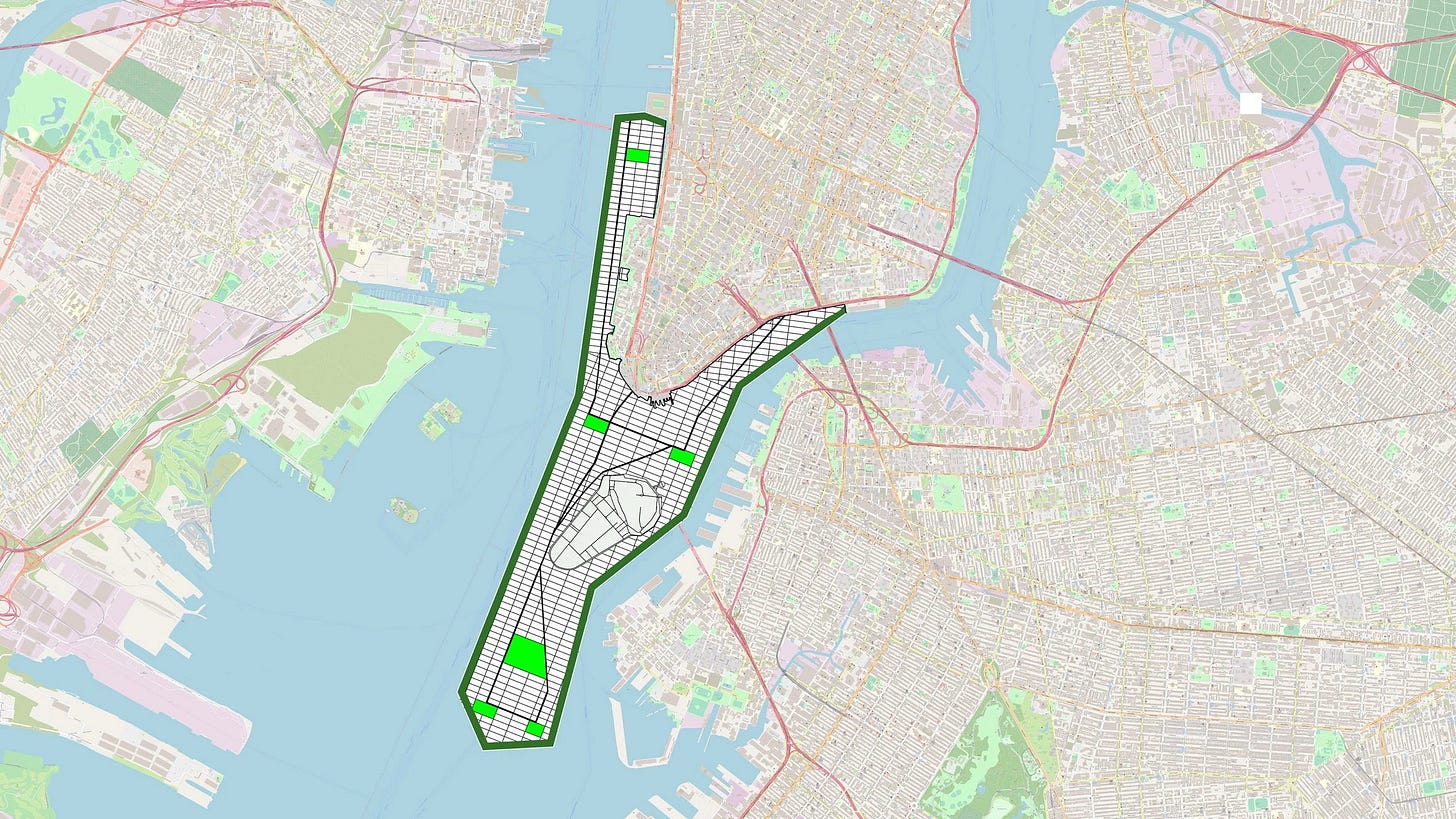

In the end we were able to get comprehensive incarceration data from North Carolina linked to administrative school records, merged at the household level. North Carolina’s NCERDC was ultimately very helpful in assembling this final dataset. This experience taught me something really valuable about the research process. If you really believe in a project, sometimes you have to be willing to push through a ridiculous amount of rejection in order to get there in the end.

The Education-Incarceration Gradient

The end product of all of this is a new paper on the educational impacts of incarceration with two of my grad student classmates, Chris Hansman and Evan Riehl.

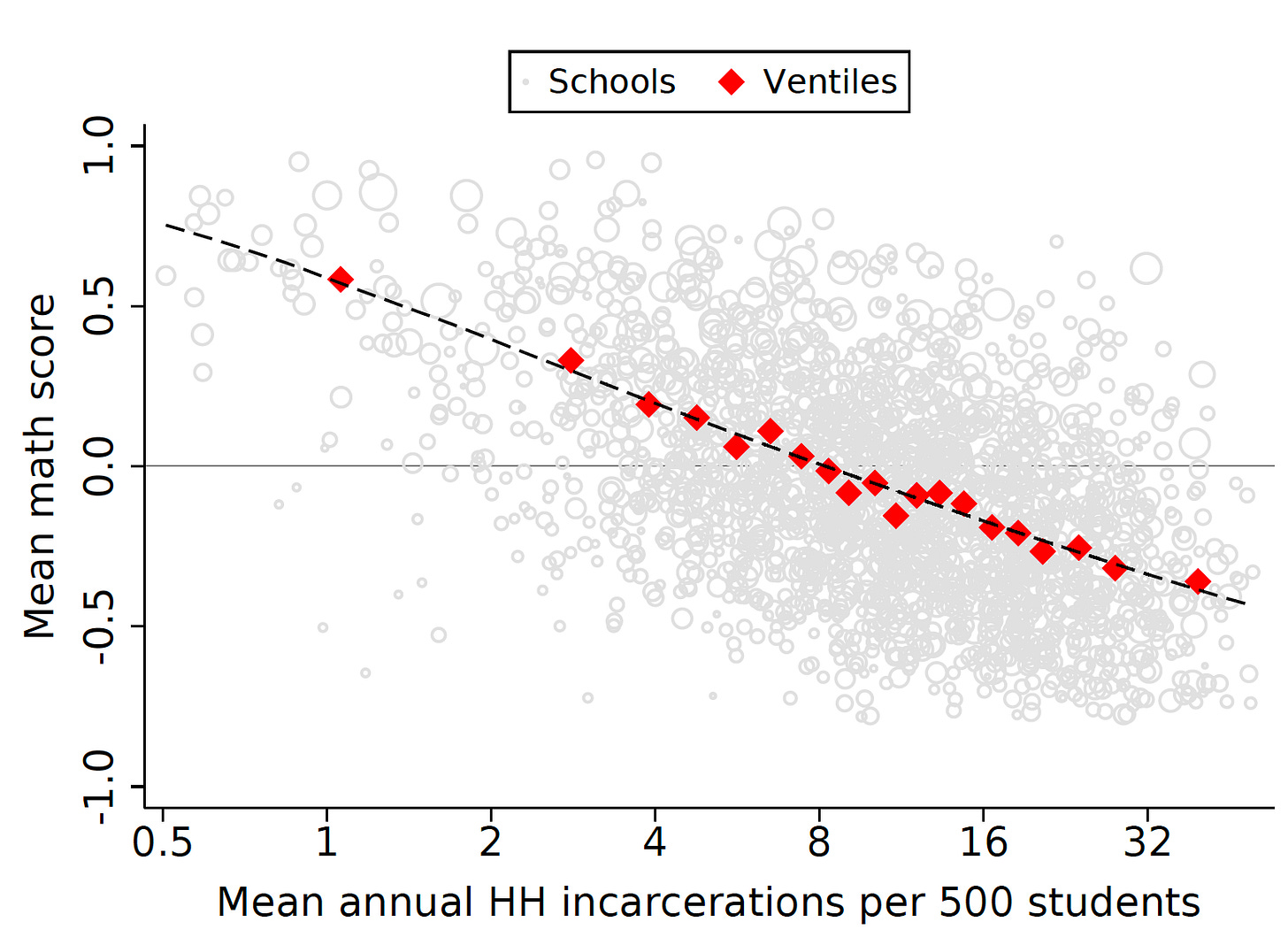

The first thing we show is there is a really strong gradient between school test scores and background exposures to incarceration— how often students have a household family member incarcerated. So there is certainly strong sorting between areas with worse educational outcomes and exposure to incarceration.

But it doesn’t establish causality, and to get at that we look at the impact of criminal judges. As a lengthy literature has now established, judges tend to vary in their sentencing severity — how likely they are to incarcerate individuals for a particular offense (this holds up in our sample as well). A one standard deviation increase in county level stringency generates a sizable shock of roughly 15–20 percent increase in the annual number of active sentences, or about 100–125 incarcerations in the average county.

We find that local exposure to more incarceration as a consequence of exogenous judicial shocks substantially and persistently worsens the academic performance of students in the area. A one standard deviation increase in county-level stringency reduces student’s math scores by 2.5–3.5 percent of a standard deviation, and reduces their English scores by 1.5–2.0 percent of a standard deviation.

This supports the idea that there is something about incarceration exposure which adversely affects student academic performance, which in turn has long-run implications for human capital achievement and access to opportunity. Students even perform worse when they personally are not subject to a background household incarceration shock themselves, which hints at the idea that incarcerations may have some spillover effect that impacts the whole community, not just the students involved.

Incarceration Spillovers

So how would these spillovers happen, and how should we think about them? Ed Lazear wrote the classic paper on classroom disruptions, and since then an extensive literature has documented that exposure to classmates prone to misbehavior worsens student performance. So what would we need for this channel to drive the overall results?

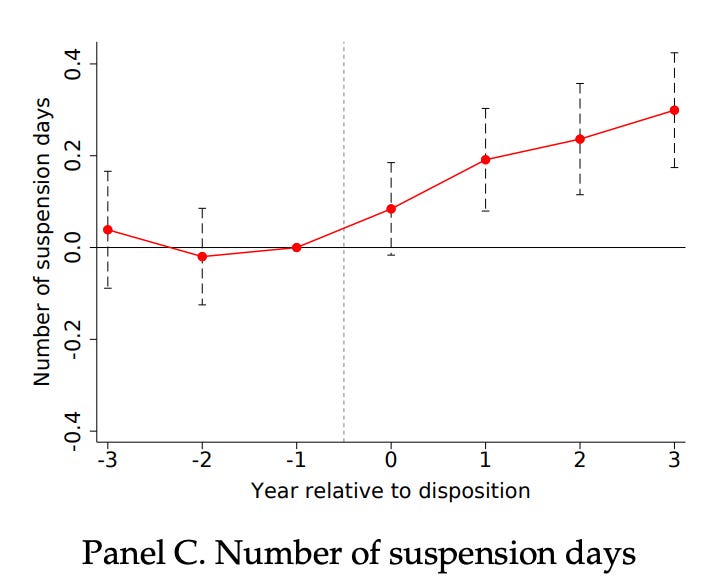

First, we would expect students directly affected by household incarceration to exhibit more misbehavior, which might then spill over to negatively impact their classmates. We find evidence for this using two separate identification strategies, which try to adjust for the natural confounds in studying this question. An event study compares children’s outcomes after facing an incarceration shock against other students whose family members were convicted of the same crime, but not incarcerated. And we also use the judicial strategy again, but this time looking at outcomes for children exposed to background incarceration only because of the sentencing severity of the judge they are assigned to.

Both approaches yield similar results — children appear to be worse off in the aftermath of household exposure to incarceration, seeing drops in test scores and increases in various measures of misbehavior and disruption. A household incarceration reduces children’s math and English scores by 1.0–1.5 percent of a standard deviation

Now other papers have looked at this channel before, finding some mixed evidence. One way to reconcile some of these findings may come from thinking of incarceration shocks as somewhat multidimensional. As some of the psychological literature has emphasized, exposure to a traumatic background event like incarceration can influence children in a variety of distinct ways, including on academic performance, disruptive behavior, and criminal activity separately. And consistent with other prior literature, we find some evidence consistent with the idea that children affected by background incarceration are actually less likely to commit crimes themselves and are more likely to ultimately move to better neighborhoods (as measured by the neighborhood socioeconomic status percentile).

What’s key though, and really novel to our paper I think, is that we then trace what happens to the classmates of students exposed to household incarceration. We find that these students also experience worse outcomes in the aftermath of students in the classroom exposed to background incarceration shocks. The effects appear to be larger when those directly affected students engage in more disruptive behavior, consistent with the misbehavior channel.

Disruptive events in the classroom itself are unlikely to be the full story, since students interact a lot outside of the school environment. However, we think this is a stand in for the broader set of spillover actions stemming from incarceration shocks.

How much of the overall gradient can these channels explain? Overall, about half the overall association of test scores and incarceration persists using our causal identification. In North Carolina, the typical student has a 2.3% chance of being directly exposed to household incarceration in a given year, while the typical child is exposed to 4.3 household incarcerations through classmates. So while direct exposures have negative consequences, they do not aggregate to explain much of the overall relationship. By contrast, smaller spillover effects on a larger fraction of peers aggregate to explain about 15% of the causal effect. The rest, if you like, is something of “dark matter” — causal associations stemming from incarceration whose mechanisms we are not able to trace out. Hopefully this is an area which future research can look into.

Overall Implications

So what do we take away from this? Demonstrating that incarceration has more negative consequences than conventionally understood, with impacts that spill over onto other residents of local communities, would on balance suggest that we do too much incarceration. One way to implement that, for instance, would be to consider spillover effects more explicitly in sentencing decisions.

However, incarceration in general does serve an important role in the criminal justice system overall in ensuring deterrence. The costs of both crime and the strategies we use to deter and address crime happen to be quite high, in ways that have collateral consequences and impair access to opportunity in different neighborhoods.

So the value of interventions which address both crime and incarceration severity are likely quite high. One possibility here I think is more certain deterrence with swift, but lower-stakes, punishment. As Alex Tabarrok has emphasized; we tried to address crime by increasing the severity of punishment more than the probability of getting caught. Under the traditional expected value of incarceration, a la Gary Becker, that should still deter crime. But when criminal have high discount rates, this winds up not reducing crime all that much — and also exposing other family members to a more substantial shock.

So criminal justice that is, as Alex says, quick, clear, and consistent can potentially provide better deterrence against crime, while also lowering the broader societal disruptions resulting from mass incarceration.

Other Links

My colleague Thomas Philippon has a really interesting paper arguing TFP growth is linear, not exponential. Some interesting discussion here by Jason Crawford:

A paper by Alex Chinco that models bubbles as forming from social interactions among speculators and FOMO. I think a valuable model to keep in mind as social media/Reddit/etc. seem to fuel interesting new waves of speculative behavior.

A deservedly praised episode of Odd Lots that highlights the 1906 Dredging Act — a protectionist piece of legislation responsible for high dredging costs, ports that are silting up, and high costs of land reclamation.

Measuring Exclusionary Zoning in the suburbs by Robert Ellickson

Causal evidence by Josh Dean that noise impairs cognitive functioning. You know all about the costs of air pollution; but it seems that noise has real costs too that we should start to address (ie, by reducing honking in cities/gas powered leaf blowers, etc.)

Thanks also to Alexey Guzey who helped to review this post.