Inflation is More Stable Than You Think

Understanding Monetary Policy through the Deposits Channel | Mass Testing

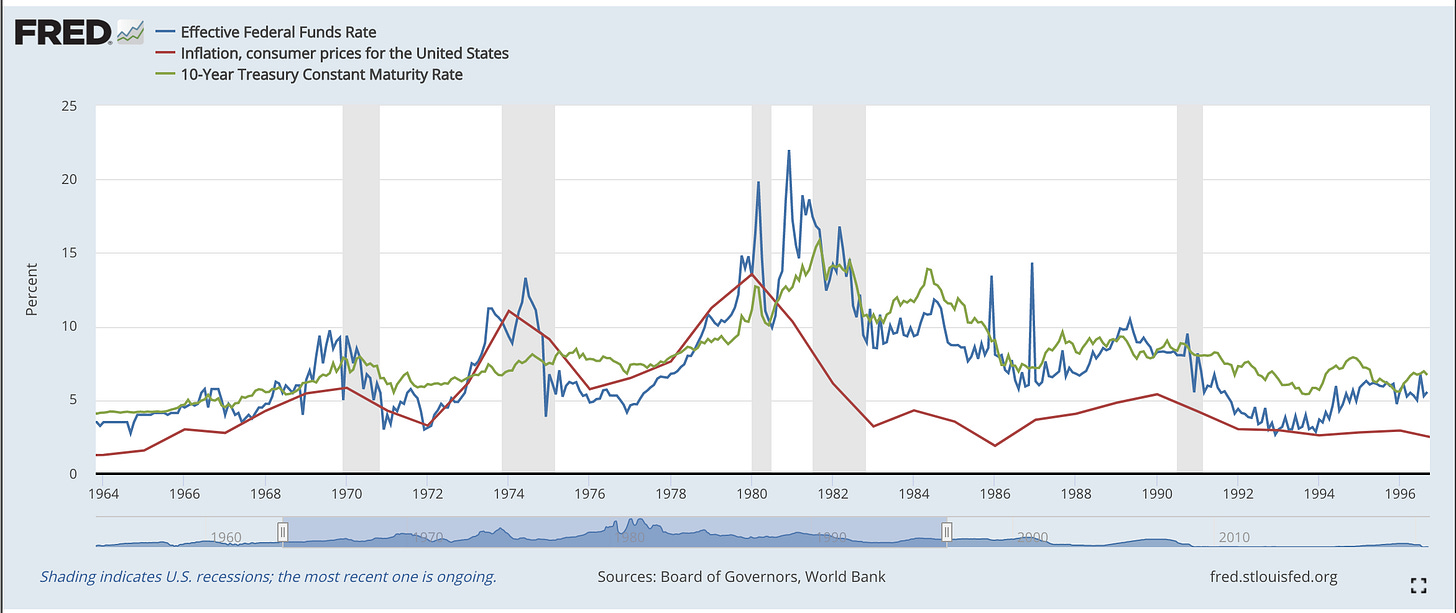

Economic theories don’t just rely on equations and empirical results. We ultimately believe theories because of narratives—stories that help organize facts and numbers. Friedman and Schwartz’s Monetary History provided a narrative structure for Monetarists. For the New Keynesians, the source narrative is a particular understanding of the Great Inflation: the time when inflation spiked to 18% in 1980 before falling.

This event, and risk it threatens of runaway inflation absent a watchful Fed—lies in the background of the recent Fed announcement to move towards level targeting. This move would allow the Fed to make up for past inflation shortfalls by letting the economy run hotter for periods of time. The reluctance to consider this previously has been motivated, I think, by fears of the Great Inflation period. So it’s worth revisiting whether those concerns hold, which my colleagues Itamar Drechsler, Alexi Savov, and Philipp Schnabl (DSS) do in a recent paper.

Flaws in the Conventional Narrative

A conventional New Keynesian narrative of this period (Clarida, Galí, Gertler 2000 QJE) blames the Fed. While inflation was rising after 1965, the Fed was raising rates—but not quite fast enough losing them “credibility,” as measured by Taylor coefficients less than one. It took Volcker’s aggressive rate hikes to finally temper inflation expectations: ushering in the Great Moderation. There have always been a few holes in the theory:

Inflation started to decline at the beginning of 1980, before Volcker’s rate hikes in Q4 of 1980.

10-year bond rates remained elevated into the 1980s. Long-term bond rates reflect expectations of future short-term rates. So if inflation expectations responded first, shouldn’t these have been reflected in prices? It actually looks like inflation moved first, and expectations were a little adaptive or extrapolative and took a long time to get reflected into bond rates.

The conventional narrative, about a whimpy Fed, explains the “inflation” but not the “stag” part of the stagflation. Why was output so low and volatile over this period? Work by Nakamura, Steinsson, Sun, Villar has tested the canonical price rigidity channel, finding low evidence of welfare losses from inflation through sticky prices. Why did the economy see not just high inflation, but recessions, during this period?

The Answer Turns out to be Reg Q

DSS have a clever explanation of this period that centers on a kind of obscure banking regulation. I think this is a really neat story that forces us to rethink how monetary policy works and the threat of future inflation.

In previous work, this team of authors has identified a Deposits Channel of monetary policy. When interest rates go up, banks take advantage of market power and don’t increase deposit rates quite as much. As a result, deposits flee the banking system. With lower assets, banks lend less—resulting in the conventional story that Fed rate hikes “drain liquidity” from the system.

The imposition of deposit limits over the period 1965-1980 meant that this mechanism kind of worked on steroids.

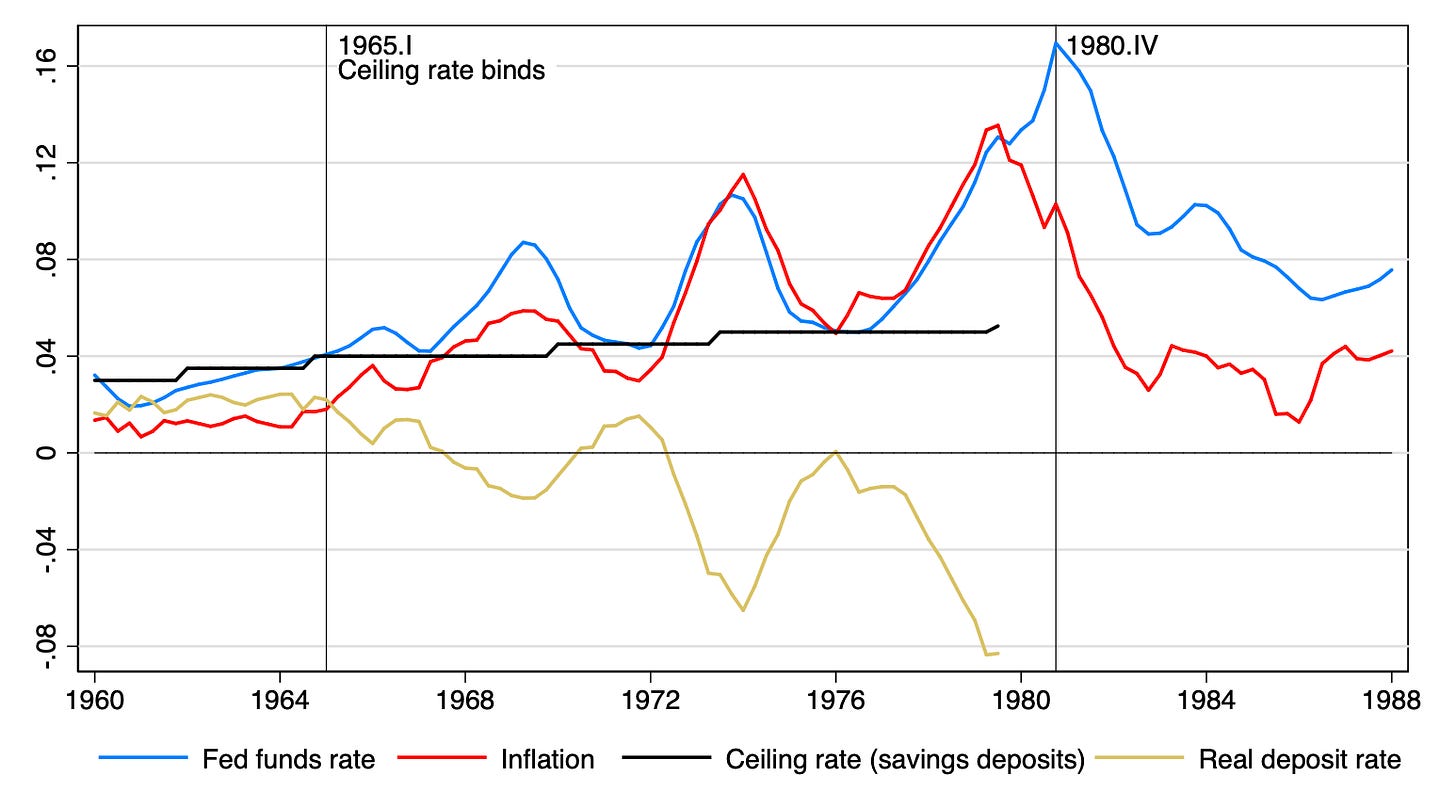

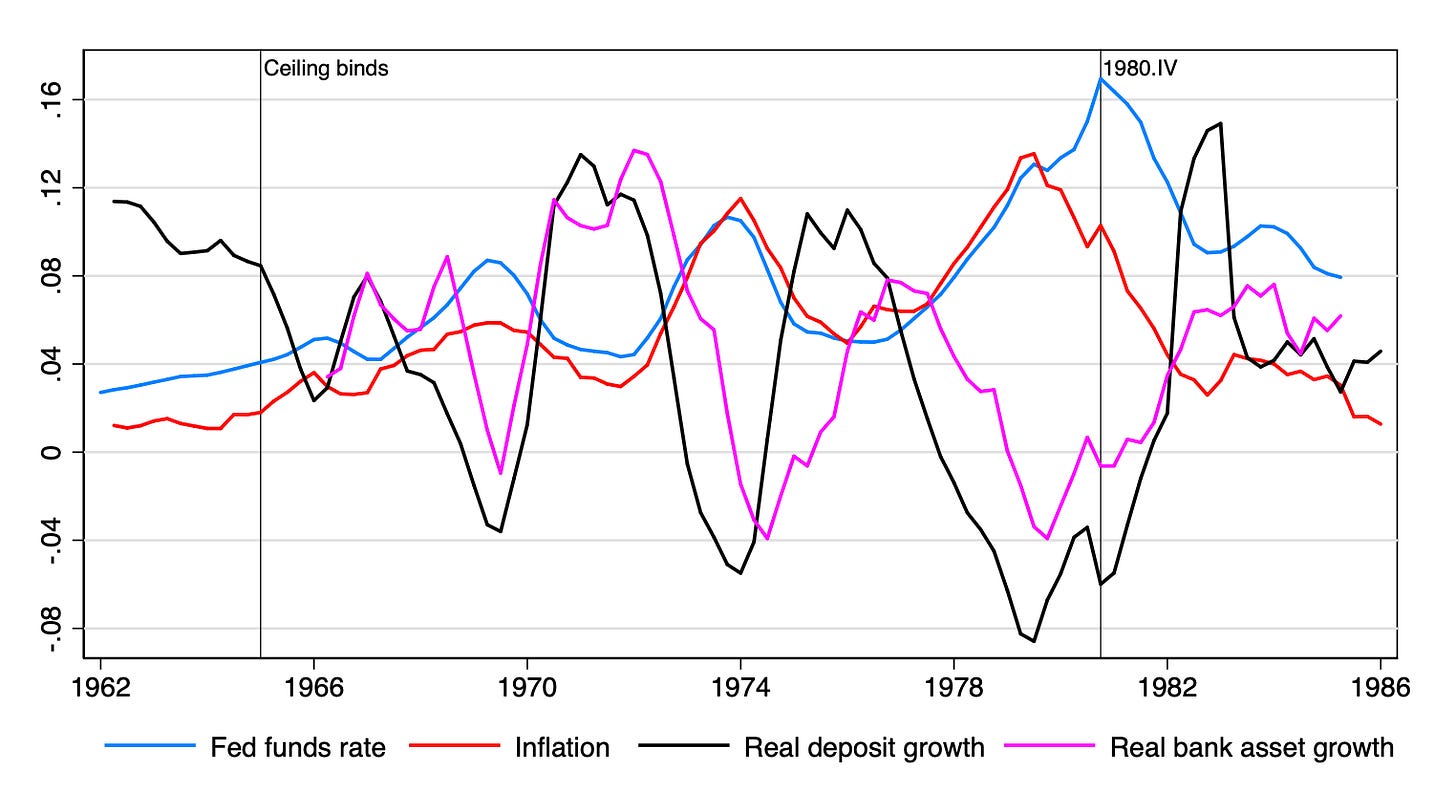

Specifically—Reg Q created a ceiling on how much banks could offer for deposit rates. Once this rate became binding in 1965, we hit a nominal peg (as discussed in Friedman’s influential 1967 AEA address). With banks unable to raise deposit rates in the face of rising inflation; depositors soon faced negative real deposit rates.

Over this period, you see that times when inflation and the Fed Funds rate exceeded the deposit ceiling imposed by Reg Q, deposits fled the system. This money was instead spent on goods and real estate—generating inflation. It also evaporated bank liabilities (their deposits)—limiting bank lending, leading to the “stag” part of stagflation.

So what finally ended the Great Inflation? The introduction of new deregulated deposit accounts finally allowed savers the ability to access higher rates, leading to a huge influx of savings (16% of GDP) back into the banking system, reducing pressure in prices. The bulk of the paper is documenting this process with micro data, but what’s important is that this all happened prior to Volcker, which ends up being a sideshow to this whole story.

How to Think About Monetary Policy Instead

Traditional macro theory has become like the Ptolemaic model—riddled with epicycles to explain what’s going on. The deposits channel view offers a very nice alternative explanation I think, with some interesting implications:

Monetary Policy looks generally stable, not unstable: Instead of worrying about the possibility of runaway inflation and credibility, we can instead look at the last 70 years as a period of pretty moderate inflation rates—interrupted only by a brief period of high rates that have to do with a weird nominal peg. Just don’t do the nominal peg thing and runaway inflation is less of a concern, and inflation level targeting, as the Fed is now planning to do, looks probably okay.

Recessions probably have a financial component generally: We conventionally separate recessions into ones that are “financial” driven and those that are “normal”—but this work complicates that. I think it’s likely that output drops in general entail a substantial financial component.

Financial Repression is really interesting to study: China is interesting to study in this regard. Artificially low deposit rates have led to cash inflows into real estate (which has seen really bubbly behavior) and shadow banking (weird products like WMPs). At the same time, China’s savings have generally been quite high. Michael Pettis likes to say this is because China’s savings net is so weak, forcing large precautionary buffers even with low rates.

India is also interesting. The entire post-2008 period has seen pretty anemic growth for India. Deposit banking institutions never really recovered from that period. Shadow banks, reliant on wholesale funding, seem to have really grown instead—before seeing their own collapse. Overall I think the economy has basically been in a silent financial crisis over this period.

Test Test Test

This has been a really big week from the standpoint of mass testing. We’ve seen Universities with mass testing plans—like UIUC and Harvard—really ramp up their activities. SUNY Purchase is pooling saliva tests. Arizona has instead deployed surveillance through sewer water to isolate cases to one dorm—followed by rapid testing everyone in that dorm to stop the spread.

By contrast we are seeing pandemic spread at Universities that have opened up in high-risk areas without continued surveillance plans—Alabama most of all, which now has 1/30 students infected. The NYT has a nice tracker for Covid cases around the country.

At the same time, Abbott has announced plans to produce $5, quick rapid tests, along with a 150 million purchase order by the Trump Administration. In particular—this includes an app which an in principle display your testing status to a third party. This offers the promise of a verified Covid state useful for contracting purposes.

So to get back into your office—test everyone on entry and show a test result to get in. Same for schools, concerts, theaters, indoor dining, etc. In principle, we don’t even need to stick to 6 ft rules and so forth—just test everyone, all the time, and we can resume normal activities.

There are concerns about lower sensitivity for these tests. But as Joshua Gans discusses a nice new article: these tests are better for what we often want to do, which is determine who is contagious. There are estimates that suggest as many as 90% of people currently tagged as Covid-positive may not actually be that infectious. Routine testing of everyone, flagging the people who are actually infectious, would be much more effective.

I am actually more optimistic about this Paul Romer-route to curbing Covid than even vaccines. Though the superforecasters are more optimistic about the arrival date for vaccines—I worry they won’t be sufficient. We know that many affluent office workers have sheltered completely during this crisis, and represent a fresh population in the event they return back to normal activity. Even if a vaccine is quite effective—we would still have high risks for superspreader activities if we returned to activities which were normal pre-Covid. I imagine these are among the key concerns for offices right now (which are at something like 8% capacity in NYC despite very low cases). No one wants to be the first person to go back to routine operations and see a superspreader event like in the famous South Korean call-center case.

Routine, mass testing for Covid through cheap rapid tests promises to solve this problem; especially for high-risk settings indoors. I don’t see any reason why we can’t drastically scale up these tests (other rapid tests if not this exact Abbott one) and return back to something resembling normal soon. One concern is what people actually do when informed of a positive test result—ideally we would have quarantine rooms available for people who want them, and social support otherwise for people to miss work.

Other Links

The case, by Brad Setser and STW that Taiwan's central bank has large forward positions to offset unhedged currency risks taken by domestic life insurers.

Very high assortative mating among wealthy Danes.

Why American traffic planners overestimate highway demand.

How parking ate up cities.

Dramatic boom in new business formation during this recession—including firms intending to hire other employees.

Market prices for medical residency slots suggest residents not a financial liability, but are generally underpaid for their labor. Also suggests are are providing financial support through Medicare for medical training all wrong.

Where people are saving commute times as a result of remote work.

Indian Covid deaths higher than you might expect given the age distribution—suggest co-morbidities may be a factor.

Countervailing supply chain network to China developing between Australia, India, and Japan.