Land Value Estimation

ASSA Roundup: Strategic Effects in Bankruptcy and Social Connectivity for Investment

At the ASSA meetings this year I had the pleasure of chairing a session on Machine Learning and Real Estate. Because of the sheer quantity of data availability on properties, real estate has been an area with a lot of “Big Data” applications even before the current buzzwords. Think the Case-Shiller Repeat Sale indices, for instance, initially put together using Deeds records from county courthouses. Since then, the range of data has really exploded, including text and images, and Machine Learning techniques are really valuable for dimension reduction, as they grow generally in popularity and I think will just become established elements of the Economist toolkit.

Measuring Land Value

I want to discuss one of the papers in the session in particular: “A Statistical Learning Approach to Land Valuation” by David Albouy and Minchul Shin. The motivation here is the classic Georgist goal of taxing land value. Henry George was an American thinker who argued for a radical shift towards land value taxation. By separating the improved value of land (ie the physical structure) from the unimproved land underneath, it would be possible to directly tax the unimproved value representing true land rents. This is a very attractive idea since you generally get less of what you tax, but there should be no economic inefficiency in taxing the land value since it’s not like we are going to get rid of any land. Henry George is sort of forgotten now, but he (and the land tax idea) were very big in the late 19th century.

A major hurdle to implementing the idea in practice is figuring out how to value the land separate from the structure in the first place. You could start by looking at just the vacant lots that do in fact transact, to start to get a baseline for unimproved land value. The problem is that these transactions are really sparse, so you’re not going to measure very much land value. You could then also look at the combined sum of land + structure value for a broader set of properties, but now you don’t have the land value by itself.

The key insight of the paper is to use Bayesian methods that combine land value estimates drawn from the unimproved sales (assumed to be unbiased estimates), along with the estimates from the full properties which provide a fuzzier signal. As you might imagine, when there are just a few local true vacant land sales, using the broader sample of properties provides a larger improvement in price estimation:

Bayesian models have, for whatever reason, not really taken off much in Economics — but I think this is an interesting use case that shows their value. We are often really interested in some sort of true underlying state value, and have a variety of signals (biased or unbiased) about that value. The estimation here ultimately estimates something potentially really interesting — the underlying value of land for every parcel — which we could in principle use for tax purposes.

Alex Chinco then gave an interesting discussion of this paper that caused me to rethink the land value framework a little bit. He argued that the intrinsic value of vacant land should really be zero. Instead, land is a derivative asset: it derives value only from the option to build something on the land. So we can draw the value of a piece of land in our usual options plot as something like this, with respect to a “strike” construction cost when it makes sense to build the property:

Under this view, there is not really a dichotomous difference between improved and unimproved land. Unimproved land only really has value to the extent that it becomes more likely that some sort of improvement will eventually get built on there. An intuitive way to think about it: suppose there was a spare parcel of land in Manhattan. It would probably sell for a lot. But suppose, instead, that we banned any form of new construction there, forever. The land might still be worth something, as a private park, but probably a lot less than before.

This idea has some complicating effects on the paper’s analysis, but it also raises some conceptual questions about whether we should tax the component of unimproved land value that proxies for the likelihood of future development. If we want to actually encourage people to exercise the construction option and build on it — I would guess that taxing the option value is similar to taxing the built structure itself in presenting a disincentive.

Update: Anthony Zhang has convinced me otherwise on optimal taxation of the development option. So the reason that taxing improved land value is potentially bad is because it amounts to a tax on investment. ie you build some structure, and the higher property tax on the whole amount reduces your after-tax income and disincentivizes the construction in the first place — an efficiency loss. If an unimproved parcel of land has value because of the option to build there, however, I now think that taxing that value doesn’t really affect your decision to exercise the option. It’s just a level shift in your after-tax proceeds from the land, which you pay whether or not you ultimately exercise the option to build in the first place.

In practical terms, I think we could still just mostly get away with taxing the whole property value, and not lose that much from disincentivized construction. We could think about land vacancy taxes, or just much easier zoning to incentivize that construction a bit more. They are not always considered in the same context, but my view is that a YIMBY-style reduction in building constraints and increases in property taxes in tandem are actually very complementary strategies towards tackling the rent holders who have our economy in a chokehold.

Strategic Effects in Bankruptcy

It’s common these days to stress the role of adverse shocks in pushing individuals to insolvency. I am very sympathetic to this channel, having looked at the effects of cancer diagnosis on bankruptcies and foreclosures myself. But I think there are also some reasons to think that strategic considerations also play a role in household default decisions.

To see that, we can compare with corporations. I really like this paper by Stephan Luck and João A. C. Santos who look at the difference in spreads between corporations that borrow using secured and unsecured debt. It turns out that, in the corporate sector, you really have to throw the whole battery of fixed effects just to get the right sign, and after a bunch of work they estimate that corporations that pledge collateral get rates about 23 basis points better than with unsecured debt.

I was really shocked when I first heard this, because any plausible estimate of this secured-unsecured spread for households is orders of magnitude larger. The 30-year fixed rate mortgage right now for instance is 2.8%, while you pay more like 16-20% to borrow on your credit card. A home equity line of credit, another comparable revolving credit line but collateralized by your house, might be anywhere from 3-8%. Student loans are not exactly collateralized, but subject to very harsh recourse and have low rates. Whereas again a random unsecured bank loan in the US might cost something like 10%.

So why is the secured-unsecured spread so much higher for households than corporations? One possibility would be market power — maybe unsecured household credit markets like credit cards are just very uncompetitive. This is not a crazy idea; Kyle Herkenhoff and Gajendran Raveendranathan estimate that the credit card industry is an oligopoly that charges well above competitive pricing, though this doesn’t explain all of the higher spreads.

I think a natural possibility is that the lender recovery situation is just very different across corporations and households. As a corporate lender, a default by a creditor can trigger either a loan covenant violation (and restructuring) and pushes you to bankruptcy quickly given enough insolvency. For households, there just… isn’t the same mechanism for a creditor to push bankruptcy. The situation is actually closer in many ways to sovereign debt, where countries take loans for foreign creditors and there just isn’t a natural mechanism to force debt repayment (ever since the gunboat era passed).

So when households take secured debt, lenders can at least repossess the collateral in the event of default. But for unsecured debt, especially, you are operating in a really minimal recourse environment — and the borrowing costs really wind up spiking. All of that suggests that strategic considerations for households, particularly on their unsecured debt, are really plausibly important considerations.

This brings an interesting paper by Bronson Argyle, Benjamin Iverson, Taylor Nadauld, and Christopher Palmer on strategic effects in bankruptcy (my discussion in AFA session here). They put together a really interesting dataset connecting debts reported to the credit bureaus against what is reported in bankruptcy filings. I think we are used to think of the credit files as a comprehensive list of personal liabilities, at least, but they argue there is a lot of “shadow debt”— things like fines, fees, medical debt, unpaid rent — that adds up as additional liability items not reported to credit bureaus.

The authors then document bankruptcy delays resulting from changes in the federal minimum wage laws, which change wage garnishing rules and seem to deter bankruptcies for a period of time. These delays allow them to examine how consumers accumulate debt given great filing delays. People appear to act “strategically” in the sense that giving people more slack results in increased shadow debt at the time of filing.

It’s not entirely clear what people are doing to accumulate this debt, but I think a plausible interpretation here is that people are doing a little gambling for resurrection. As people delay filing for a bit, they wind up racking up additional necessities and expenses, even outside the formal credit report, which wind up following them as they file for bankruptcy. These actions dilute existing creditors, who have to now share creditor proceeds with these other classes of creditors, and so this is evidence of some interesting moral hazard or strategic behavior in the context of consumer bankruptcy. It’s a reasonable example of the sort of strategic behavior that seems to result in higher credit losses, which ultimately flows back in the form of high rates of consumer borrowing.

One thing that I still don’t understand in this accounting is why real estate seems to play a large role in corporate lending decisions, and why the change in the economy from tangible to intangible assets appears to have led to a slowdown in bank lending. Banks are somehow able to both collateralize the cash flow stream from corporations so well that they don’t charge a much higher premium whether you actually pledge collateral or not; but also really care that you have some tangible collateral to pledge in lending. Maybe bank lending really responds to collateral on the quantity, but not pricing side?

Social Connections and Investment

The other paper I discussed at the AFA was “Social Proximity to Capital: Implications for Investors and Firms” by Theresa Kuchler, Yan Li, Lin Peng, Johannes Stroebel, and Dexin Zhou (discussion here). So Johannes argued that not all papers actually follow this format of a hyper-tight instrument, and instead follow the a more narrative format:

I think this paper is a good example. The authors:

Have a story — social connections between regions influence where institutional investors choose to invest.

This is backed up by a baseline correlation of the social connectivity of regions, as measured by the number of common Facebook friends between areas, and investment as measured in 13fs.

This pattern also shows up in outcomes like liquidity.

And shows up also for all sorts of other patterns, like which firms seem to be affected, and how investment responds to shocks (Hurricane Sandy).

My discussion here was a chance to think about what, exactly, social connectedness between regions is actually capturing. I think there are three main things this picks up:

You are more likely to share information and do business with people you know personally. This direct contact peer channel doesn’t really scale very much (limited by something like Dunbar’s number, or ~150 close contacts).

You might share a group affinity with someone, and so rely on a shared network which helps with contract enforcement. This goes back at least to Avner Greif’s work on the Magribi Traders. This extends social ties beyond people you know personally, but will be limited to some group identity (which could include religion, ethnicity, caste, University, etc.).

I think there is actually a higher structure here of broad regional familiarity or affinity. So this is going to be similar to home bias — you have a preference to invest in areas “close” to you — but closeness can be something like cultural familiarity. You put these items in your consideration set of what to invest in, while you will not for other products far away.

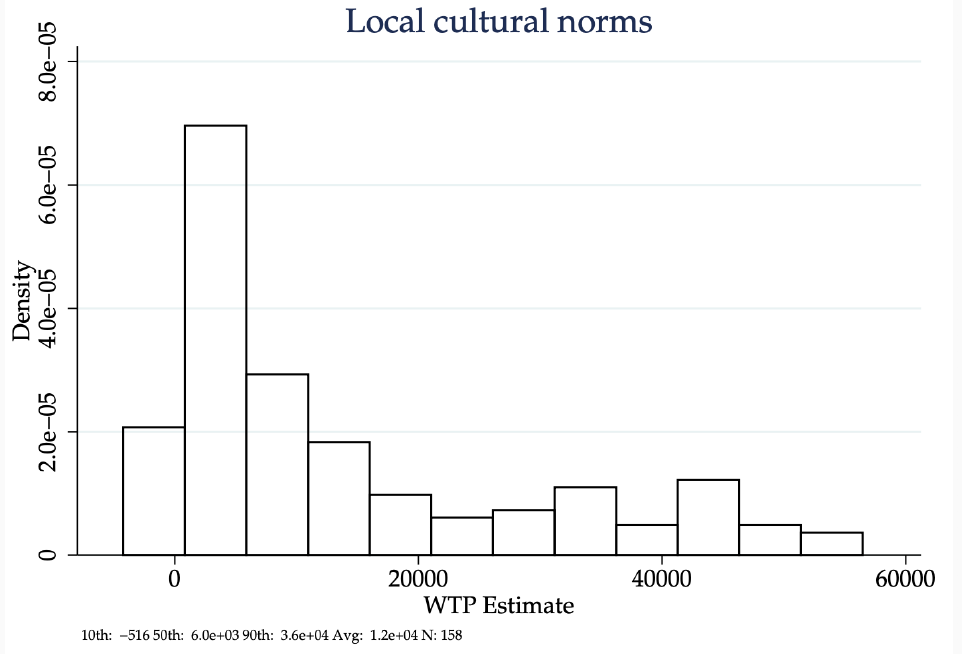

What is interesting about this paper is that it provides evidence that is actually most consistent with explanation 3 here — that there seems to be an aspect of broad regional comfort driving investment decisions. This is not the only place we see this behavior; an interesting paper by Gizem Kosar, Tyler Ransom, and Wilbert van der Klaauw uses a survey to estimate willingness to pay (WTP) for migration, and finds that people actually seem to value local cultural norms in their migration choices, even above and beyond their connections to friends and family:

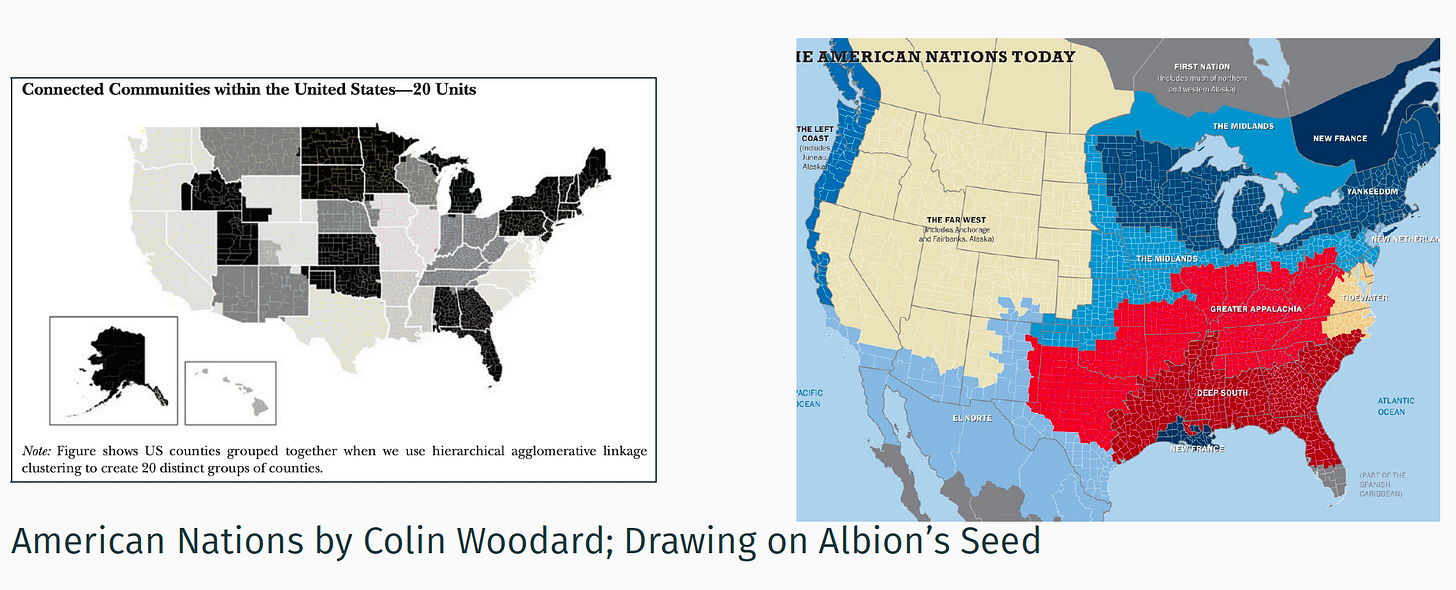

I think this behavior is pretty natural if you have heard people say things like “I don’t really like Minnesota — people are very passive aggressive there” or “People are just too aggressive in the Northeast” or “I like how polite folks are in the South.” Even though the US is a pretty culturally homogenous region, there are still pretty large differences in norms and behaviors across areas. People familiar with one set of practices will generally find it easier to interact with other people who share those expectations — even when they don’t know each other personally, and aren’t even the member of any specific affinity group. Ultimately, these cultural differences may stem from the specific history of settlement in the United States, which line up with a partitioning of the US along the lines of social connectedness if you squint a bit:

So I think there is some interesting higher level structure of American society, at levels like region or urban v. rural, that are proxied by our social networks. And as we stratify ourselves along dimensions like Red Tribe v. Blue Tribe, whether we believe election results, or how comfortable we are with Covid risk, we are going to generate these fractured but commingling shared realities.

Q: Don't assessors already evaluate the land value? They need to in order to support the tax write-off of asset depreciation. The IRS does not allow you to depreciate land values, only improvements. Why isn't this assessment viable?