COVID-19 has been a shot directly at the heart of what makes cities vibrant—the amenities which draw people for plays, retail, restaurants, etc. have been shut down; and at the same time offices have been largely closed while people work remotely. Under those contexts, it is maybe unsurprising that people have moved elsewhere. But are those shifts temporary or permanent? How is this impacting the real estate market—which is seeing an unprecedented boom? Is this pandemic just a temporary blip in the factors that make cities great, or are the ongoing shifts accelerants of broader social changes?

We explore these questions in a recently updated Working Paper with Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, Vrinda Mittal, and Jonas Peeters; you can see a short presentation of the project below (and another link here). Here, I want to pick up a few of the threads in the paper and think about future trends.

COVID-19: A Permanent or Transitory Shock?

We do a few things to break apart whether the pandemic is transitory or permanent. First we look at rents contrasted with prices. The rental market is a spot market: the inventory clears period-by-period (subject to some vacancy) meeting demand. The housing market is more forward looking, incorporating expectations of future changes.

And rental markets have really changed. We look at the rental gradient (or bid-rent curve)—the extent to which being closer to the center of the city carries a premium. This has basically disappeared completely across a sample of 30 MSAs, while the price premium has declined somewhat but not by as much. This tells us the transitory effects of the pandemic are pretty strong, virtually eliminating the premium for urban space in the short-term market, and much higher than the permanent changes captured in prices.

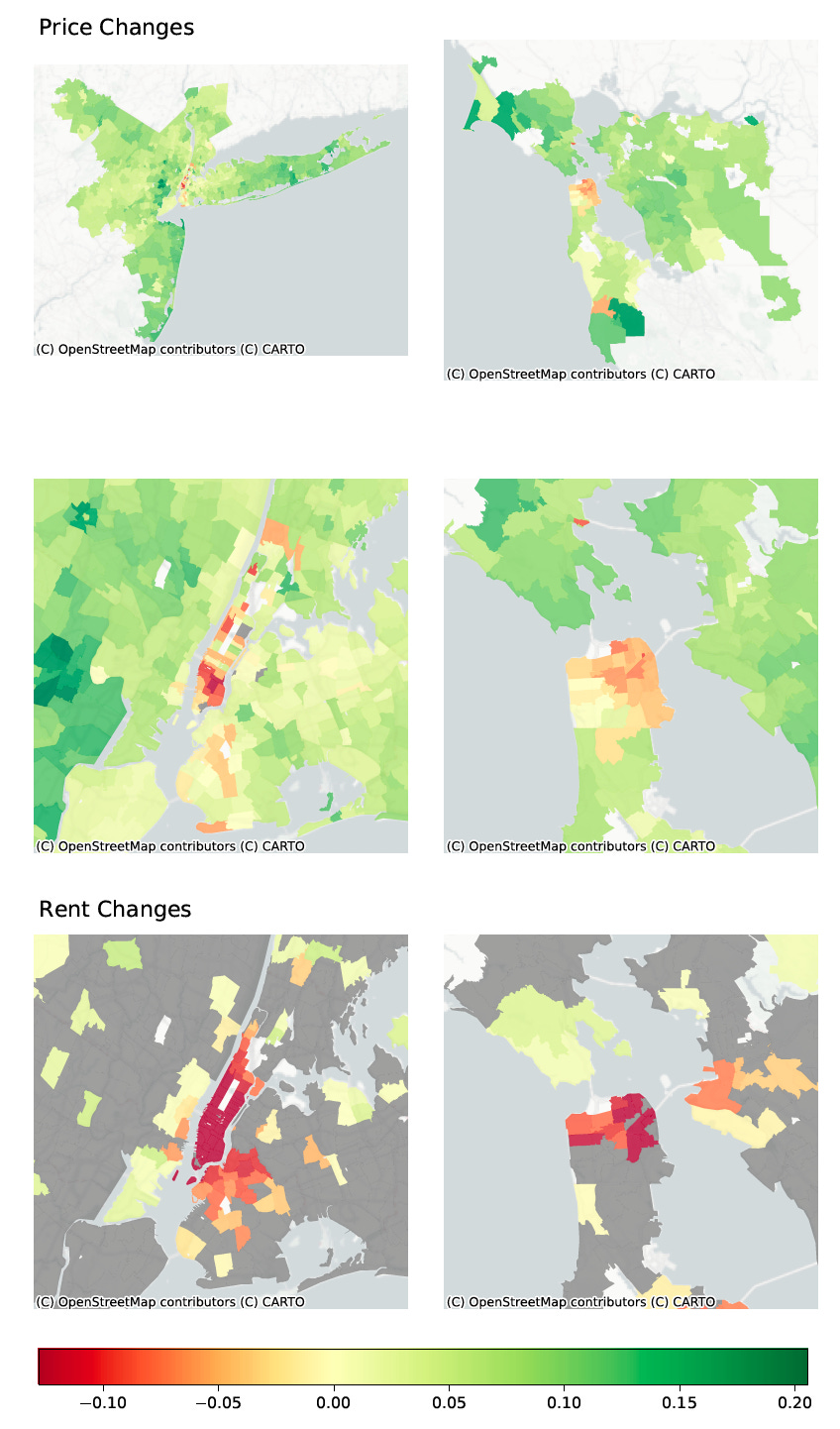

You can get a clear visual sense of these trends by looking at the Bay Area and New York—two of the most affected superstar cities. Prices—but especially rents—are really going down in the urban centers which used to command a large premium; and going up in the wide swath of suburban land around cities.

By the way, this is why there is not really a “puzzle” of rents and prices moving in opposite directions. You see trajectories of urban revaluation across both rents and prices—just much weaker in prices, which reflect the permanent component of revaluation.

In the paper, we also look at survey data on whether this will be a permanent or transitory shock, and estimate the degree of urban recovery. In the context of a Campbell-Shiller decomposition, we estimate that future rents will rise to justify the current level of prices. Cities aren’t dead, but they are temporarily shocked and partially reshaped by remote work.

Remote Work and Cities

When we look at the cross-section—across MSAs; and within cities across ZIP codes—there is one factor which clearly predicts changes in migration and real estate patterns: the share of people who can work remotely.

In general, this could reflect two main things. Remote workers tend to be exactly the sort of highly educated urban professionals who have recently flocked to cities for amenities, and may now be reassessing urban attractions even on a permanent basis. It’s an interesting paradox, as Lukas Althoff, Fabian Eckert, Sharat Ganapati, and Conor Walsh explore, that the people who have packed themselves most densely at the centers of cities are also the same people who could, potentially, do that job remotely.

The other channel—and I personally think this is the main one—is that we have had a drastic shift in remote working norms enabling persistent changes in residential location. I draw a lot here from Adam Ozimek and Nick Bloom. Barrero, Bloom, and Davis, for example, have a survey which highlights the importance of the “hybrid” model—30% of workers here want to work remotely all the time (enabling moves outside the MSA), while 10% of people want to be in the office all the time. The remaining 60% of workers envision a future where they will show up to the office some number of days in the week, but not all.

What the hybrid model enables is a resorting of desired residential location within your MSA. If you think you have a fixed commuting budget; you might be willing to spend a little bit longer commuting each way, if you make the trip fewer times a week.

We see evidence of this in a recent NYT piece by Jed Kolko, Emily Badger and Quoctrung Bui; which uses USPS change of address data to track moves. You see big relative change in migration in metros like New York, San Jose, and San Francisco—these areas have the combination of high remote work (opening up the possibility of moving) combined with NIMBYism and supply constraints (high costs, and high incentives to move out).

Within these metro area, we see large migration in the extreme exurban fringes of cities like New York—which are also the same areas where we saw high price changes. Many of these places are actually outside the technical MSA boundary, and were not even really considered commutable before—but that was on the old five-day-a-week schedule. Remote work opens up a broader radius in which you can optimize your housing choices.

Supply Constraints and Agglomeration Economies

This brings up questions about whether these changes in real estate choices are actually good. Cities, after all, are home to all of these great agglomeration economies. Will a more suburban America feature lower growth, if we miss out on all of the great water cooler talk and post-work drinks that fuel innovation?

I think the first-best solution here is clear—just build enough housing in dense, productive cities so people can access affordable housing stock in the cities they work in. The problem is we have made superstar cities, where attractive jobs are located, impossible to build in. Urban economists are inclined to attribute some of the resulting urban premium to people moving to cities in order to access urban amenities, and that’s surely part of the story. But many workers are simply forced to pay high Bay Area and New York City rents to access jobs, which means that rising rents have just eaten up a large chunk of economic gains. In the absence of YIMBY efforts in these cities, increased remote work is a new force which pushes against those economic constraints to open up new working possibilities elsewhere.

I’m ultimately optimistic that firms are going to be able to figure out how to internalize benefits of the agglomerations that happen within-firm. Jamie Dimon, for instance, has been a remote-work skeptic—but is still anticipating a world with 40% less office demand. JP Morgan is projecting just 10% of workers being fully remote, but being able to hot-desk workers who come in only a few days each week. It’s easy to imagine Midtown Manhattan, and other large office centers under the old commuting model, being really badly affected as a result.

The external links across firms are harder to address, because firms don’t face natural incentives to encourage employees to interact with workers from competing firms. Still, I think we need to think harder about what these cross-firm spillovers actually entail. One of my favorite papers here is by Boris Hirsch, Elke Jahn, Alan Manning, and Michael Oberfichtner, who find that a large chunk of the urban wage premium in Germany just reflects more competition in urban areas, and less market power, rather than productivity differences. It’s possible this result generalizes more broadly—in which case a key question is whether firms are going to allow fully remote hiring of workers.

Greater access to high quality jobs all around the country, rather than to just people willing to move to a handful of select metros, would drastically open up pathways for opportunity—and also rebound in the form of increased spending in local communities. My own view is that trend towards greater spatial equality is one we should welcome, even it comes at the cost of intangible agglomeration economies—in part because it would address the problem of communities which have fallen behind and fallen prey to bad information bubbles. But this is not an obvious question.

The one other X-factor I’ll throw in here is crime. In the dark days of American cities in the 1970s and 1980s—they remained cultural hubs and places where young people would gravitate towards. It’s just that many people moved out as soon as they started to have families—and the problem of urban crime was a key part of that. It’s too soon to tell how crime patterns are changing in cities, but the future trajectory there will clearly also determine how cities fare.

Very interesting.

I do think there's a serious possibility that hybrid-remote work actually increases spatial inequality though. Hybrid-remote work enabling white-collar workers to relocate to the exurbs seems like it encourages metros to become more like Chicago, with extreme white-collar job concentration in the Loop coupled with extreme residential dispersal. And this entails Chicago-style service-sector job dispersal, where workers without college degrees face much thinner labor markets.