Property Taxes and Housing Allocation under Financial Constraints

How Property Taxes Could Restore Housing Affordability for Young Families

We’re dealing with a housing affordability problem in this country, which is particularly tough for young buyers. House prices and rents shot up over the pandemic, driven by remote work and low interest rates. And even as rates have gone back up, house prices have not, possibly due to low housing inventory and mortgage lock-in by existing owners. That combination of high prices and an established ownership base presents a huge challenge for new buyers.

I have a new paper with Josh Coven, Sebastian Golder, and Abdoulaye Ndiaye on property taxes which sheds some light on what’s going on here, and points to some policy tools to address them using traditional property tax instruments.

The Housing Mismatch Problem

The basic issue here is that a majority of bedrooms in owner-occupied homes are owned by people between 50 and 70 years old—empty nesters who often have more space than they need. Meanwhile, younger families with children frequently find themselves in crowded living situations, unable to afford homes with adequate space.

This is also highlighted in Redfin research, which finds empty nesters own 28% of large homes, while millennials with children own just 14%.

What this means for the typical lifecycle for the American family is that households are struggling with cramped living space as they start families in their 20s or 30s. Eventually, many households accumulate the down payment (or else are given them as a gift) to buy their own place. But they are often forced to choose between a large suburban house in a worse job market; or cramped living quarters in better job markets. These pressures are probably responsible, on some margin, for rising ages of marriage and childbearing; greater cohabitation with parents; and declining fertility rates, which are a big macro concern these days.

Households do accumulate more and more housing over the lifecycle; but this means that they are left aging in place in large, spacious homes. In our model, households accumulate these assets due to a bequest motive to pass them along to their children. However, the collective consequence of everyone investing in homes for intergenerational purposes pushes up the price of housing, and results in a lot of empty bedrooms in the hands of the elderly. By the time owners pass away, in their 70s or 80s; the next generation are frequently empty nesters themselves in their 50s. It also makes life harder for aging populations, which may lack a local younger workforce for essential care services.

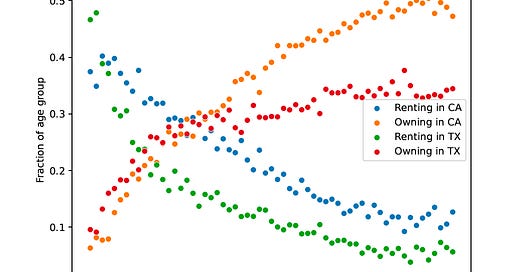

These challenges are all amplified in high housing cost markets, like California, where you see extremely low ownership rates among younger households:

The “Forced Mortgage” Mechanism

So what’s going on in California? The central force, we argue in the paper, is low property tax rates resulting from Proposition 13. The key insight is that property taxes function as a kind of a “forced mortgage.” Higher property taxes tend to lower the upfront purchase price of homes through capitalization. Essentially, future tax obligations get priced in to the current home value. Property taxes therefore result in a lower initial out of pocket equity investment, as well higher ongoing costs in the form of annual property tax payments, which is equivalent to what mortgages typically do.

The lower prices attract young buyers, as they make down payment requirements more attainable for young, cash-constrained buyers. The higher user cost of owning housing pushes out aging empty nesters and encourages them to downsize. Overall, this tradeoff from higher property taxes is particularly beneficial for young families who have steady incomes to cover the ongoing payments but struggle to save the large lump sum needed for a traditional down payment in expensive housing markets.

We show that, across the United States, spatial variation in property tax rates is generally consistent with this story going on. Areas with higher property tax rates feature:

More young homeowners

Fewer empty bedrooms

A higher percentage of children in the population

Lower house prices and price-to-rent ratios

All of which are consistent with the idea that property taxes play a role in shaping housing allocation across generations. This is in contrast to a standard intuition you might hear from, say, cranky homeowners in New Jersey or Connecticut, who insist their property taxes amount to a large cost and burden. While this may be true for such homeowners now; these same cost burdens likely facilitated their entry into that housing stock in the first place. Meanwhile, hopeful homeowners in, say, San Francisco are looking at local housing inventory that is mostly locked up and priced out of range for them, and so often depart to other states to buy homes.

California vs. Texas: A Natural Experiment

To further quantify these effects, we build a detailed structural economic model calibrated to match the housing markets of California, as an example of a high property tax state and Texas, which is a classic example of a high property tax state (has no state tax instead).

The model successfully replicates key features of both housing markets, including the steeper relationship between age and homeownership in California compared to Texas.

Using their model, we then run a policy counterfactual: What if California raised its property taxes to match Texas levels? We find:

Overall homeownership in California would increase by 4.6%

Young household homeownership would jump by 7.4%

House prices would fall by about 18% due to capitalization

In-migration to California would increase, especially among younger households

Out-migration from California would decrease

Total wealth would decline (due to lower house values), but incomes would rise slightly as people gain access to California's higher-wage job market

Policies like California's Proposition 13, intended to protect homeowners from rising taxes, may therefore have had the unintended effect of making it harder for young families to enter the housing market. Homeownership for the young would be considerably more attainable under higher California property taxes.

Implementing Georgist Solutions

Our paper is positive rather than normative, in that it focuses on the role for asset taxes like property taxes on equilibrium prices and quantities in the presence of financial constraints but doesn’t take a stance on the desirability. It’s a close cousin of other work which has highlighted the efficiency benefits of wealth taxes; the role for depreciating licenses and Harberger taxes; and the value of dividend rather than corporate taxes for corporate taxes; and of course the Henry George land value tax tradition broadly.

All of these papers have a similar flavor: identifying some market inefficiency, and focusing taxes on correcting this distortion in a way that raises as much money as possible with as few costs.

But I think it’s also worth thinking about the implementation challenges to making something like this happen, should policymakers want them to. On the one hand, there is a clear constituency of possible supporters — the young should favor this policy, as they are prime beneficiaries. It offers them a way to both tap into the increased wealth in real estate generated over the last few years, while also easing on affordability burdens into the future. Of course, there is a just as motivated a set of opponents in the form of existing owners.

The key aspect of political economy which seems to help property taxes in the US is the tie to the funding of local public goods. Property taxes make up something like half of local government revenue in the US, which is actually substantially higher than rates in Europe. Many European countries focus their real estate taxes on transactions based taxes, which instead further increases lock-in.

In California, the key issue, as Jake Krimmel has argued, was school finance equalization, removing local control. The anti-property tax backlash emerged afterwards, and then municipalities saw new construction would give them additional liabilities (school and infrastructure expenses), without a corresponding property tax stream, and they turned to exclusionary housing regulation to keep out newcomers.

By contrast, many Sunbelt states have value capture property tax instruments (MUDs in Texas, SIDs in Nevada, and CFDs in Arizona) which use property tax revenue in the future to pay off municipal bonds issued to build infrastructure today.

So one possibility would be to innovate on the use of property tax revenue to help finance necessary investments today (maybe in childcare, eldercare, mass transit, the green transition, or lowering other local taxes); which might build a broader political economy coalition to allow for more taxes on land value.

Elsewhere

Vital City has a great new issue out on the prospects for an “urban doom loop,” a term that has come out of our research on the impacts of work-from-home and the pandemic on cities. Together with Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, we have one essay evaluating where we stand on the urban doom loop thesis; and another one analyzing the viability of office to residential conversions to tackle urban decay.