So far, this newsletter has traced the impact of pandemic on the initial migration waves out of urban centers, which were sustained due to remote work. This led to large shifts in residential value out to the suburbs, as many built home offices. Now that we are two years into the pandemic, people are back to handshakes and travel — but remote work endures, and is likely to be one of the most impactful legacies of the pandemic.

The next part of this research agenda is a new paper I have with Vrinda Mittal and Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh on the flip side of the trend — if people are working at home, what happens to the commercial office?

The CBD

Most American cities were historically anchored around a commercial office hub into which workers commute daily. In New York City, for instance, over half of all city tax revenue comes from real estate (mostly in the form of property taxes, but also including mortgage and transfer taxes). A sizable chunk of this reflects commercial office values, which made up between $172-175 billion in value before the pandemic.

Looking at the value of this real estate through the pandemic is useful for two reasons. First, we can use the market prices that are available on a subset of these assets (generally, the higher value buildings are more likely to be held by REITs and publicly traded) to learn about the disruptive impacts of technological innovation from remote work. Second, the value is important in its own right — it sustains municipal finances, underlies financial instruments (mortgages and equity held by the financial system), and sustains spillovers in the form of retail around city centers.

Shocks to Office Valuation

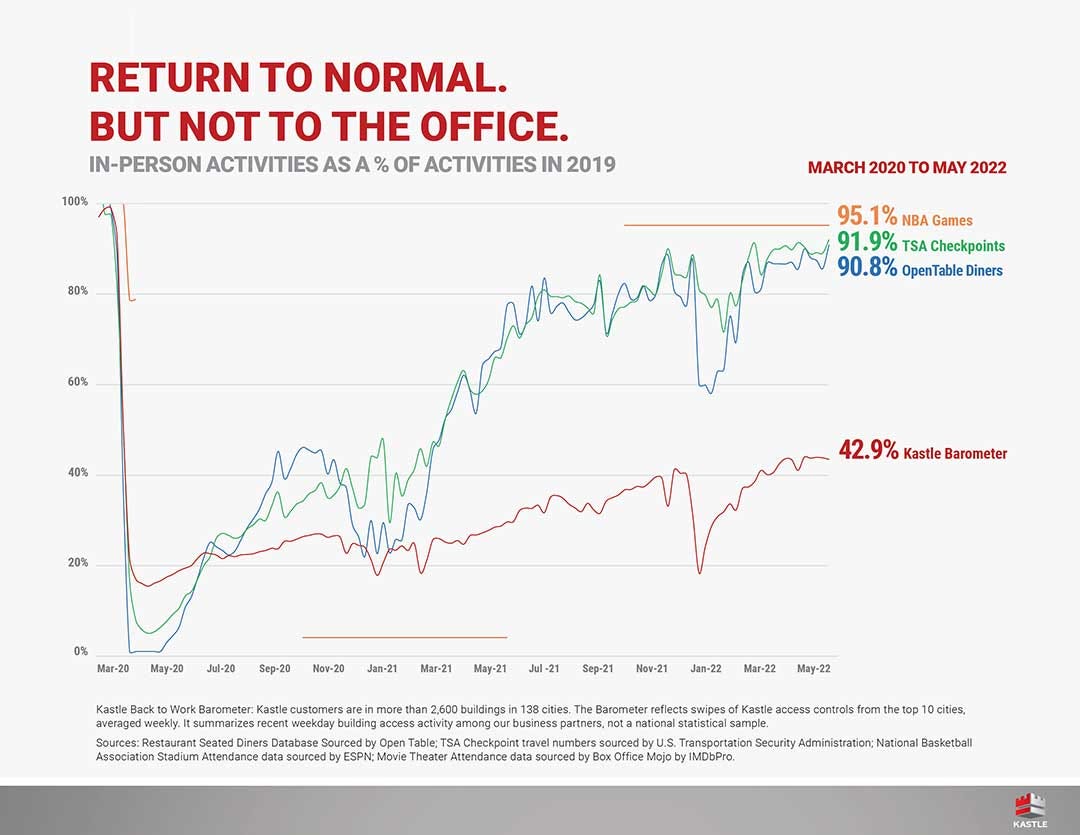

So what’s happened with offices? Well, we know that people have held off going back to the office, even as other activities have resumed in person:

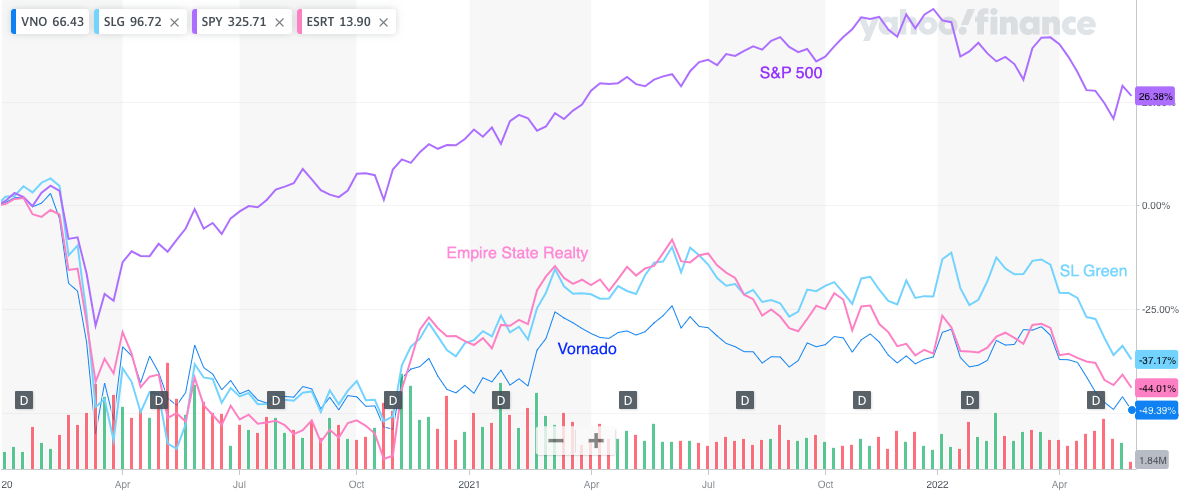

We can also look at the three major NYC-based REITs, which are publicly traded baskets of commercial office assets, to get a sense of the general trends. These stocks show a decline of 37-49% since before the pandemic; compared to a rise of 26% for the market overall.

We can also look at lease revenue. This is another incomplete measure, because commercial leases are long-term, so only a fraction of commercial tenants have had to make an active decision on what to do with the space yet. But still we see substantial decreases in overall leasing revenue, reflecting mostly higher vacancies; particularly for the lower amenity buildings as opposed to the higher value “A+” buildings (we’ll come back to this). When we look at the cross-section of firms: it’s precisely those companies that have a lot of remote hiring that are lowering their office demand.

Estimating Office Value in the Remote Working Era

In addition to documenting some trends in commercial office demand, the main thing we do in this paper is think about the problem of valuing commercial real estate, either at the building or real estate portfolio level. To do that, we need to take into account the discount rate, or risk, as well as the future cash flows. And we also want to account for the possibility of future downturns, and the idea that remote work might be persistent or else revert back to what it was previously.

The basic idea here is to take advantage of the fact that real estate is a bit of a split beast between publicly traded and privately listed vehicles. We try to learn what we can from public instruments, where we have the benefit of frequent and fresh market prices. But then we extrapolate some of that to the broader set of office assets which are not always publicly listed to learn about the full universe of real estate; sort of in the spirit of what we had done to learn about private equity.

In terms of risk, one interesting thing is that commercial office REIT returns, during the pandemic, start to covary with a “WFH” risk factor, which you can think of as something like the returns of Zoom minus Carnival cruise stock. Office returns, in other words, are now pricing in the risk that remote work might be an important risk for offices.

For the cash flows, we account for four states: a normal expansion, normal recession; a work from home recession (ie, the initial post-pandemic period) and a work from home expansion (the rest of the post-pandemic period). The idea is that we transitioned from the non-remote work expansion directly to a WFH recession in 2020, and we use the size of the commercial REIT market drop to help calibrate the implied persistence of remote work into the future. If the market expected a rapid return to a non-remote future, we wouldn’t have expected office REITs to drop very much. So, instead, the larger impact on office REITs points to a world in which remote work appears to be more persistent.

We combine these discount rate and cash flow shocks into an asset pricing model. The main result from all of this is an estimate of office valuation. We see a 32% decline in value initially as we hit that remote work recession state, which goes in the long run (after ten years) to a 28% decline. So part of the effect of the pandemic is transitory reflecting the immediate recession, but we’re forecasting a substantial value hit to offices.

Just as important as the average effect is the dispersion — there remains a lot of risk and uncertainty around the evolution of future office value, reflecting both recession risk as well as the chance of remote work remaining persistent. We have one sample path that shows the WFH forever future; this features office valuations that are 39% lower in 2029 compared to 2019. So remote work really is a big and important deal, and its effects are strongly felt in the office real estate sector.

Flight to Quality in Offices

Another aspect of the data that pops out is the differential effect on high-amenity buildings — those that are younger, more expensive, and are generally nicer — compared to the low quality older buildings. Here, for instance, you can see the net effective rent (NER) for young buildings in New York actually rises, compared to declines in rent for the older buildings.

This fits in with lots of media observations and our anecdotal conversations about the return back to the office. Many firms are downsizing; and moving to hot desks with hybrid work, and generally rethinking what they need the office for. You don’t need to use offices for getting work done in isolation as much, since people can do that at home. Instead, you really want to optimize on the sorts of collaboration and discussion that physical space is great for, and you need to incentivize people to come in. High quality space, and space that’s oriented around those collaborative functions, works best at that.

The Future of Cities

The low quality office space, by contrast, is much more at risk at being a “stranded asset” in the wake of the technological disruptions coming from remote work. What’s going to happen to these spaces instead? Many are looking at conversions into residential space. One benefit here is that older office buildings tend to have smaller floor plates (ie, the buildings are more narrow and have more surface area to interior space) which means they are more conducive to turning them into residential properties.

What are the other impacts on cities? So far, urban governments haven’t really had to grapple with these dislocations, due to the amount of federal subsidies that have come in, as well as the boost the residential property values. But I think the loss of the office anchor core will be a big shock to cities down the road. The whole transportation networks for many cities is intensely tied to office commuting; and ridership numbers remain persistently down as people aren’t coming in. This raises concerns about “ridership death traps” as metro systems might not be able to sustain viable riderships down the road, triggering service cuts that push even more people into remote work.

I don’t think the impact of all these shocks is impossible for cities to deal with; but I think it certainly calls for more effective governance and leadership. Ultimately cities need to figure out what core services and advantages they can offer even when people have a choice over where to live. Business as usual in terms of underwhelming schooling, lackadaisical police responses, unimaginable cost bloat across infrastructure construction and bureaucracy generally were survivable problems in the past, but maybe it’s time to step it up a little bit now that Tiebout competition is raring its head.

Homelessness and Cities

Another related quality of life issue for cities is the growing problem of homelessness, and I have a new piece in City Journal which looks at the issue further. There are substantial increases in the homeless population over the last decade in tandem with increases in rents and house prices; and the issues are especially bad in the largest metropolitan areas that have regulatory restrictions on housing supply.

One of the most important restrictions, I think, is the supply of Single Room Occupancy (SRO) units. It used to be the case that New York, and many other cities, had a lot of housing stock that wasn’t very high quality, but provided people a lifeline to live in. We have steadily removed this slice of the housing stock for well intentioned reasons, but it’s amplified the affordability problems in large cities, and seem to be leaving more people without options but to live on the streets.

Other Links

Increasing New York City’s tree cover by 10% would reduce heat related deaths by 3,800 and increase economic value by $32 billion. Phoenix would see a 22% reduction in mortality from baseline.

Interesting data on which states export/import college graduates:

One of the most robust results in urban economics is that January temperature really predicts migration; with the long-run trend being for people to go to the Sunbelt. I had assumed this was about consumer amenities and temperature, but this article makes the case that actually it’s warm temperature being associated with lower productivity. Once the South got AC, they closed the income gap with the rest of the country, and saw greater migration.