The Goods-Services Rotation Theory of Inflation

Why the pandemic sectoral reallocation of consumption provides the best account of the last few years

What happened with inflation over the last few years? In my view, the goods-services rotation theory of the pandemic gives the most holistic understanding of inflation and macro trends over the last several years. This paper by Veronica Guerrieri, Guido Lorenzoni, Ludwig Straub, and Iván Werning does a great job at laying out the core thesis. Francesco Ferrante, Sebastian Graves and Matteo Iacoviello also have a nice paper here on the demand reallocation story (which they think accounts for 3.5 percentage points of inflation in the last few years).

The Services to Goods Rotation

The backdrop here is that goods prices have been steadily getting cheaper over many decades, relative to services prices. This is a natural consequence of Baumol’s cost disease and more rapid productivity growth in manufacturing.

The pandemic led to drastic shifts in this pattern, as many categories of consumption became risky or prohibited from the perspective of Covid risk. This affected every sector in different ways; but a rough way to categorize the impacts is to say that services were heavily shocked (think haircuts, dentist appointments, in-person restaurants, etc.) relative to goods (autos, luxury watches, housing). This shows up pretty clearly in the data, when you can see a large sectoral reallocation away from services towards goods, which slowly reverses over the next few years as the economy reopens.

Under an assumption of flexible prices, this kind of sectoral reallocation would work out just fine: people buy more cars and houses, buy fewer haircuts and dentist appointments; and so we might expect the prices of goods to rise while the price of services falls in comparison. Instead, price rigidity is asymmetric: goods prices rose, while service prices didn’t really fall, despite the large fall in demand. After a while, goods prices mostly flattened out, not declining much in absolute terms, and so the goods/services price ratio was restored through a steady rise in service prices.

Because of this interaction of price rigidity and sectoral impacts, you can get aggregate inflation even if total spending doesn’t change at all: the first rotation to goods increases the overall price level, and the second rotation back to services does as well.

The Role of Supply

This is an account which emphasizes supply shocks, but it’s important to emphasize these are supply shocks in the services sector as a result of the pandemic, which steadily got cleared up as mandated and voluntary restrictions on ordinary life were were removed — though it’s interesting that service spending has remained below trend, while goods spending has remained far above trend.

In addition to the services supply shock; there were additional supply shocks to certain goods producing sectors — autos is a great example; as many car manufacturers cancelled orders for chips, and took a long time to obtain enough replacement supplies. Over time, these pandemic goods disruptions worked themselves out, helping to explain a component of the drop in inflation. Energy is another tangible example of a supply shock; and seems to have left a more lingering impact in Europe.

Despite the partial role for supply disruption in explaining a component of inflation in goods; I think the balance of evidence suggests at least some, if not most, of the net inflationary effect was driven by the sectoral shifting of demand. To take a relatively niche category, the price of luxury watches shot up, despite production being higher in 2021 than in 2019, before slowly deflating over time. Container traffic in volume was higher in 2021 and 2022 than in 2019; the bottlenecks in shipping seem as a result to be the product mostly of even more goods trying to reach consumers, rather than reductions in net supply. It’s not completely confirming evidence: but it is interesting that total real consumption, even in sectors like autos, went up a lot, as did the stock prices and earnings of large auto manufacturers, retailers, and goods producers in general.

Real estate is probably the best example of this trend: housing completions continued to rise steadily throughout the pandemic; while housing starts went up too. Despite construction times rising in housing; it seems pretty clear here that rising house prices have primarily been the product of higher demand (driven in turn by remote work and negative real interest rates), rather than falling supply. This is a fairly clear example of a sector in which pandemic related disruptions in ordinary life resulted in large shifts in demand to categories of consumption which were more sheltered, ie a large personal home.

The Role for Policy

Even if we can explain the bulk of the pandemic related factors with the goods-to-services rotation story; what additional role did policy play? We engaged in substantial fiscal and monetary stimulus in the beginning of the pandemic, followed by policy tightening that coincided (but did not necessarily cause) the fall in inflation.

This relates to a fundamental question about what the nature of the pandemic shock actually was: was it a 2008-style of massive aggregate shock, from which we should expect large and persistent declines in output; or was it more like a natural disaster — a shock that tends to result in a short and somewhat voluntary declines in output, followed by quick recovery?

With the benefit of hindsight, I think it is more likely we assess Covid as being more like a natural disaster shock: the voluntary and temporary decline in consumption of services was inevitably going to be followed by a recovery as soon as that sector came back, just like turning the economy on and off.

Consistent with this idea, we’ve seen broadly V-shaped recoveries across the entire world; regardless of the scale of stimulus the country has engaged in. One good example here I think is India, which did relatively little stimulus, and has come out of the pandemic as one of the world’s fastest growing economies.

As Guerrieri et al. point out: there’s a clear role for policy under this situation: provide insurance to households facing drops to income. However, they suggest that expansionary fiscal and monetary policy might be less effective under these circumstances: when service consumption is shut down, incremental demand is going to be pushed into the goods sector, which are already facing capacity constraints. Pushing even further demand into this sector, already elevated as a result of sectoral reallocation, can potentially push up prices even further.

Consistent with this view is the role of excess savings: the increase in household cash buffers as a consequence of lower spending on service consumption; higher income (as a result of fiscal transfers), and higher wealth (as a result of lower interest rates and higher discounting). This facilitates “dissaving” from late 2021 onwards — spending out of income at a greater rate than previously.

People have called into question the presence and nature of these excess savings; but it’s pretty evident looking at consumer bank deposits that households saw a large increase in liquid cash, which they have slowly started to spend down/move into higher interest rate products over time.

So while some degree of stimulus was helpful to maintain incomes; the incremental increase in aggregate demand may have simply further boosted inflation concenrated in goods. As a result, ultimately increasing interest rates (at least to a more neutral position) may be part of a helpful process of normalizing inflation.

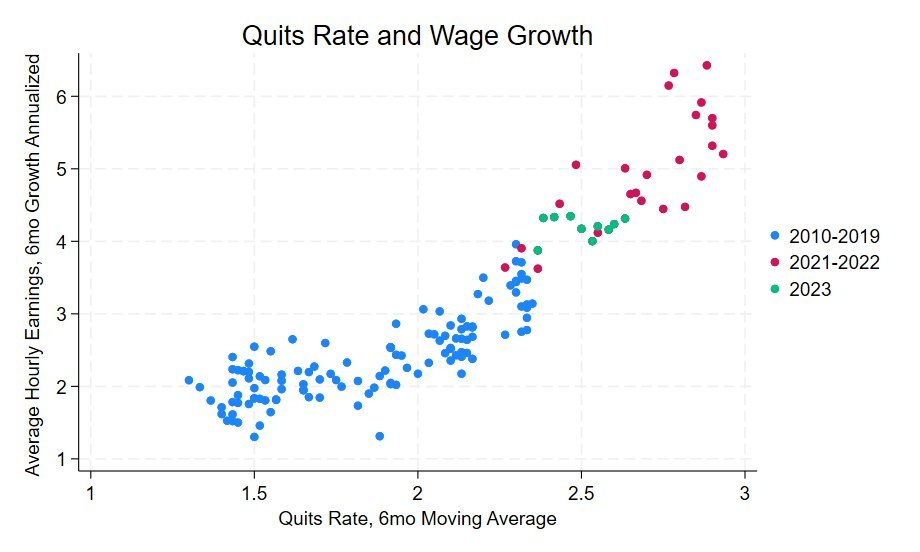

There are a couple of refinements here that are interesting. First, Justin Bloesch has argued that Phillips Curve thinking works if you use the quit rate as your measure of slack against wage growth. So imagine here that you have particularly tight labor market activity in the really active part of the labor market in 2021-2022, and things moderate a bit by 2023 (either because sectoral demand shifts into other sectors of the economy, or aggregate demand falls a bit). That gets you rapid wage growth in 2021-2022, also fueling inflation, which lowers by 2023.

Similarly, Pierpaolo Benigno and Gauti Eggertsson argue for a non-linear Phillips Curve. As labor market tightness gets particularly high; inflation really starts to shoot up. I think you could imagine labor market tightness here as a product of: 1) high labor demand in goods and other industries which remained operational during the pandemic; 2) low labor supply due to pandemic risk and other concerns; and 3) potentially a proxy for low “slack” in the economy overall, including also the goods side of the economy. The nonlinearity means that further boosts to economic activity in the inelastic part really push up inflation; but at the same time, incrementally cooling down the economy can achieve an “immaculate disinflation.” Benigno and Eggertsson also attempt to measure supply shocks — which they proxy through a few different methods (difference between headline and core CPI/PCE; and differences between import prices and the GDP deflator); and don’t find these have been particularly large recently by historical standards.

We can contrast these views with other aspects of “mainstream” macro thinking here which involves incorporating expectations about inflation, which don’t seem to fully fit this situation. Rather than inflation expectations leading the rise in inflation; instead you see expectations generally lagging contemporary shifts in inflation on the ground. The risk in the models is that inflation gets entrenched somehow, requiring even more proportionate increases in interest rates to re-anchor expectations.

However, it’s not obvious that sort of story even fits the 1970s; or the present day. Inflation seems more a product of conditions on the ground at the moment, rather than the more complicated forward-looking story. If anything, one stabilizing force might be that when faced with high and uncertain inflation, many people seem to respond on surveys as being fairly pessimistic in their economic attitudes. To the extent that influences consumption; that may lead them to actually lower their spending today, rather than accelerating it forward (which they would do if they really thought inflation would be higher in the future). Which is to say it seems there may be some stabilizing dynamics with respect to inflation, rather than the destabilizing ones that macroeconomists typically assume.

Another miss here is thinking about the labor market: Larry Summers and others were ultimately quite pessimistic about the labor supply side, and this was a key reason behind their prediction that the economy needed a recession (no way to cool off the overheated job market absent higher unemployment). This follows a lot of pessimism, in the 2010s, about the marginal productivity of laid off workers. Instead, it turns out the labor market was able absorb many additional workers, both in the 2010s and from 2021 onward, particularly into some of these “rotated” sectors.

Conclusion

The pandemic period of inflation deserves to be considered in its own right; not as a simple restatement of previous trends. With the benefit of hindsight; it seems like the economy wasn’t in as much risk of remaining either stagnation in demand (as it was in the 2010s) or in persistent inflation (as in the 1970s). We experienced a fairly historically unique set of circumstances resulting in a sectoral reallocation of spending towards goods and then back to services, and this pattern can explain a lot of the features we saw in the last few years.