The Inevitable Rise of Electric Vehicles

Why Positive and Negative Feedback Mechanisms will End Gas Cars

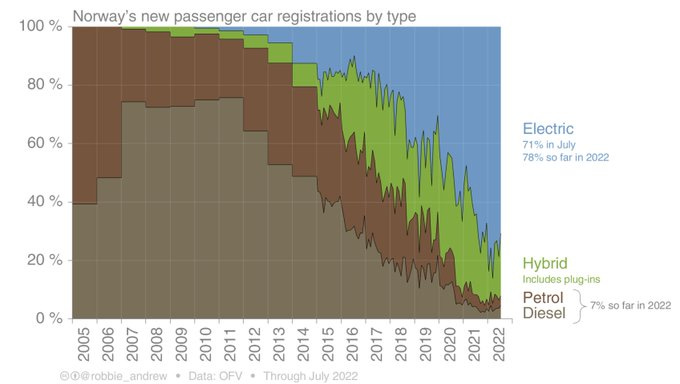

A lot of technological adoption features “S”-shaped growth curves — and Electric Vehicles are no exception. They start from a low point of adoption, then hit an inflection point of very rapid consumer growth, before reaching market saturation. Norway is the best example of this, where essentially all new cars sold are EVs (or hybrid/plugin).

Rapid EV adoption has pretty large-scale consequences on a host of downstream activities. Of course, not all vehicles are EV yet in Norway, since the car fleet turns over somewhat slowly (The US fleet turns over every fifteen years maybe) But still, gas consumption seems to be down pretty substantially in the country, and as many miles are travelled through EVs as Diesel.

Rapid EV adoption in Norway is the product of pretty aggressive policy — both in sticks like carbon and vehicle pricing as well as carrots like free EV parking. But it’s simply at the leading edge of a trend which is likely to impact the whole world. We are on the verge of a pretty complete transformation of much of the world’s transportation infrastructure to EVs, one which we should expect to happen by market forces alone, though policy can certainly nudge it along further.

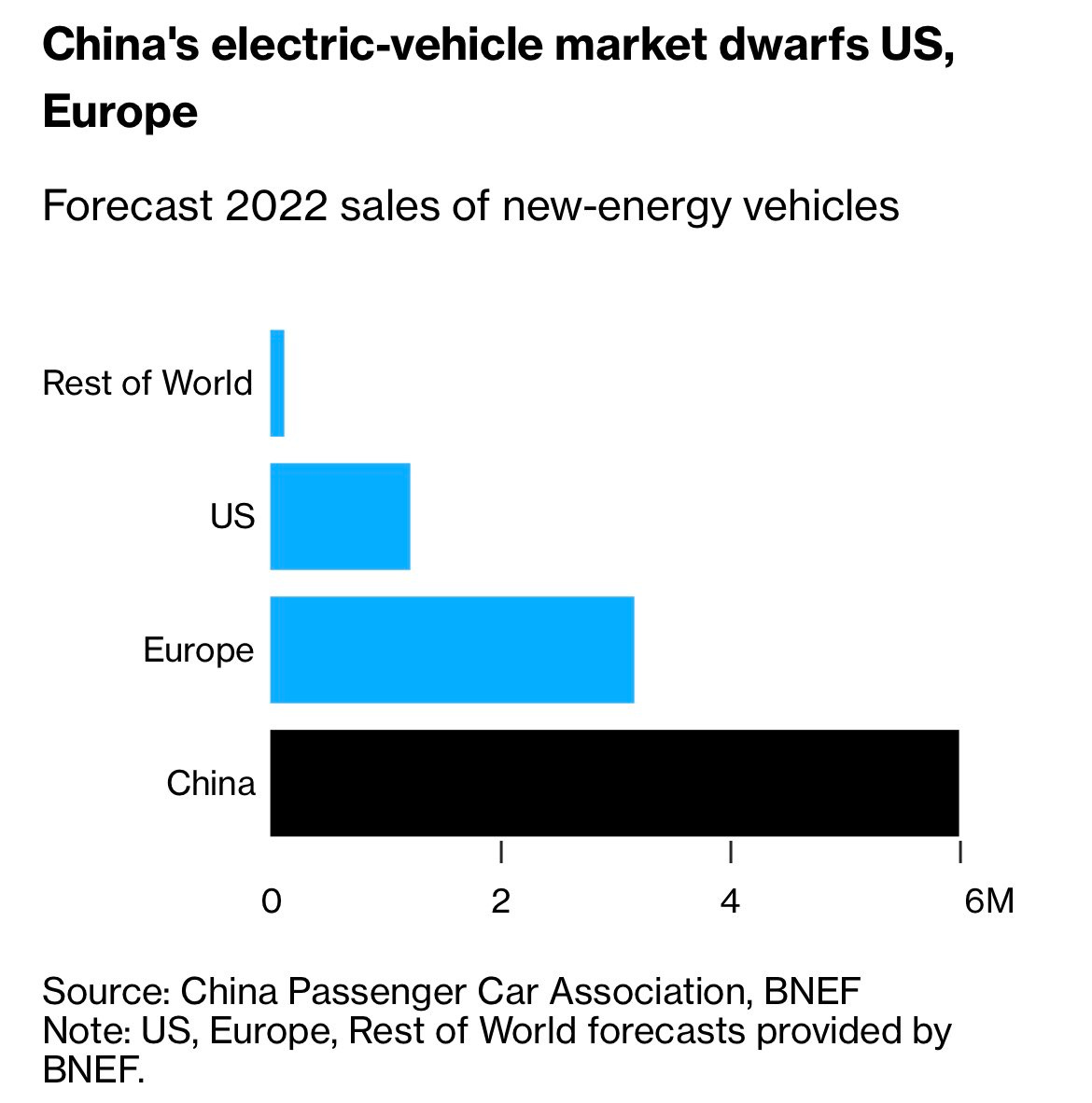

This will handle a large chunk of the overall decarbonization efforts (about a fourth of global carbon dioxide emissions are transportation-related), especially as the complementary energy generation also goes renewable. Globally, EV sales are seeing really strong growth:

And they make up about 15% of new car sales in California:

Positive Feedback Loops

This kind of rapid technological adoption typically happens when there are some sort of positive (or negative) feedback loops. On the positive side, you have virtuous cycles by which some consumers getting EVs raises the benefits (or otherwise lowers the cost) for others to adopt EVs too. This sort of thing happens all the time in technology, often as a part of platforms which get thicker or more liquid with more consumer adoption.

The most obvious part of this with EVs is with charging — more EVs help to sustain a denser charger network making it easier for new buyers. Norway for instance just has a really massive charger network, and research emphasizes the importance of the charger network effects here.

Negative Feedback Lops

What’s also interesting though are the negative feedback loops that will steadily encourage more EV adoption by people who currently use ICT cars — whether or not they really want to, just as a matter of pure economics.

For example, think about gas stations. If you’re thinking about starting a gas station today (or underwriting a loan to a gas station) — you’re making a substantial long-lived capital investment, and so want to incorporate long-run gas demand into your decision today. As a result, a declining share of ICT cars is going to hit decisions to build gas stations well before we even see the EVs show up.

What this means for your typical ICT car owner is that, over time, gas stations are just going to get harder and harder to find; and the remaining ones are probably going to remain viable by raising their markups, so your incremental cost of purchasing gas is going to keep rising. This slowly dwindling gas filling system is going to ultimately raise the financial and hassle burdens of gas car ownership until more and more of those people switch over.

We have a lot of gas stations in the US — some are probably going to find new lives as EV charging facilities tied with convenience stores, but overall the charging demand is just much lower for EVs (since they can charge at home, or maybe plugged in while parked at a retail establishment), so you’re going to need to find a new home for these. It’s also going to be a massive superfund-style environmental headache, given gas seeped into the soil and so forth.

Gas car ownership is also pretty intensive in maintenance, especially relative to EVs. As a consequence, we have a whole ancillary industry built around car maintenance, with plenty of dealers and repair shops maintaining extensive legacy libraries of parts and skilled mechanics. Ongoing investments in these areas can be justified if people will continue to operate gas cars into the future; and they all become obsolescent if people switch to EVs.

So you’re probably going to see people decide not to invest in becoming a car mechanic today, repair and mechanics shops steadily close down, they’re going to charge more if they are still open, and it will just get harder to find spare parts and keep ICT cars going — you’re going to kind of live in a Mad Max world overall if you opt to still operate an ICT vehicle.

Sunk Assets

A particularly important part of this mechanism revolves around the asset value themselves. The rise of EVs is a classic example of a disruptive technology shock — one that creates a lot of new value, but also destroys a lot of value locked up in incumbents.

If you look at household balance sheets today — you see a large chunk is devoted to holding ICT cars, especially in the lowest income quartiles:

And if you look at liabilities — 5% of all consumer credit is devoted to auto loans, or about $800 billion, with the car manufacturers themselves pretty involved in the financing activities of vehicles they produce (famously, GM most of all).

This existing value is very likely to head to zero over a medium-ish time scale as all gas cars go obsolete.

Now, car buyers and auto lending companies certainly anticipate some of this — it’s well known that cars depreciate in value as soon as they leave the lot, so people plan for the steady decline in value over time.

But an interesting — and somewhat open — question is what might happen if this depreciation happens sooner than expected due to the rapid growth of EVs.

How’s that going to happen? Well, you can think of the value of a new car today as deriving, in substantial part, from the ability to resell that same car down the road in the future on the used car market. Certain brands — BMW for instance — pride themselves on relative low value loss, which sustains higher prices for new cars.

That long-term or residual demand comes from the existence of a large and deep enough pool of buyers in the future. But as the flow of new car buyers (whether they are in the market for a new or used car) switches towards EV demand, this residual or resale value is going to go down pretty quick too. As just one entity here, think about rental car fleets — they are probably soon enough going to junk all of their ICT cars and rebuild fleets based on EVs, which is going to put severe pressure on the value of the ICT fleet.

So you might end up with a substantial sunk asset problem — ICT cars just dropping quite rapidly in price, and buyers also avoiding ICT cars just because they are afraid of the worsening resale value down the road.

The Industrial Organization of the Auto Sector

Another interesting question is who is going to actually make all of these EVs. A common assumption is that legacy car manufacturers will just make electric versions of their current product offerings and people will buy those instead. And maybe that will happen.

But it’s interesting to see that, historically, large technological disruptions also changed the nature of firms involved. When we switched from horse-drawn carriages to automobiles, for instance, the old horse-carriage companies certainly tried to adapt — they just took out the horse and added a motor (incidentally 38% of cars were already electric back in 1900).

Eventually, these companies all went bankrupt and the first generation of pure-play auto makers dominated the industry for the next hundred years.

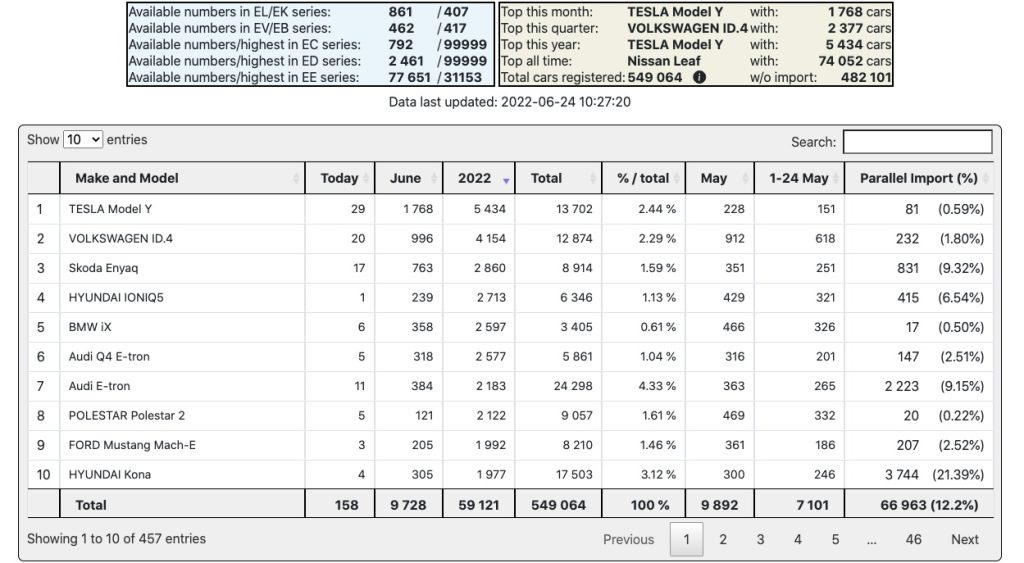

I think there’s at least a chance that we see that cycle repeat itself. If you look in Norway, you see Teslas are pretty dominant. Tesla is even more dominant in California. The picture is a little different in China, which has a host of domestic auto manufacturing companies, but there’s not much role for other traditional auto makers selling EV cars.

The hope for Tesla, in particular, is that they retain enough monopoly power due to exclusive access to the superior Supercharger system. Even if they open it up more, in principle, you might imagine they charge more or throttle charging speeds or something. Certainly you need some sort of mechanism like this in order to justify Tesla’s extraordinary stock price. But as long as there is a perception of something like this it’s an important positive feedback loop — it delivers Tesla an extremely low cost of capital today, which further boosts its own innovation and deployment efforts.

By contrast the legacy EV makers are also just so tied to the economics of the old model — between the manufacturers, the dealers (EV more often sold direct to consumer), maintainers, and financing — that it’s very hard for them to self-disrupt and see the loss in value for the rest of their business as they shift to a new technology.

Podcasts

This Week in India

I started a new series running through developments in the Indian economy — the first set of threads here gets a lot into industrialization and associated challenges, and I’ll try to use this newsletter to keep track of this series.