The Pandemic's Surprising Effects on Inequality

Why the Rich did worse than the Poor in India

There is a pretty widespread, and reasonable, belief that the pandemic has widened inequities in society. This would happen quite naturally if the poor are more exposed to disease risk and labor market challenges compared to the rich, who instead might be sheltered by virtue of remote work and sheltering. Joe Stiglitz lays out the basic idea, but you can find examples of this everywhere:

COVID-19 has exposed and exacerbated inequalities between countries just as it has within countries. The least developed economies have poorer health conditions, health systems that are less prepared to deal with the pandemic, and people living in conditions that make them more vulnerable to contagion, and they simply do not have the resources that advanced economies have to respond to the economic aftermath.

Now, to be sure, we see evidence of the negative impacts of the pandemic any many domains of activity. But Walter Scheidel offers a different perspective in The Great Leveler, in which he argues that inequality has basically only fallen during plagues and violent cataclysms. So what direction does this go in? Higher or lower inequality resulting from the pandemic?

The Pandemic’s Impact on Poverty and Inequality

We looked at this in a paper with Anup Malani and Bartosz Woda focusing on India. The first thing to emphasize is the pandemic’s impact on poverty, which The Economist graphed for us nicely. After the pandemic — particularly in lockdown, but continuing through afterwards — we see more people in extreme poverty.

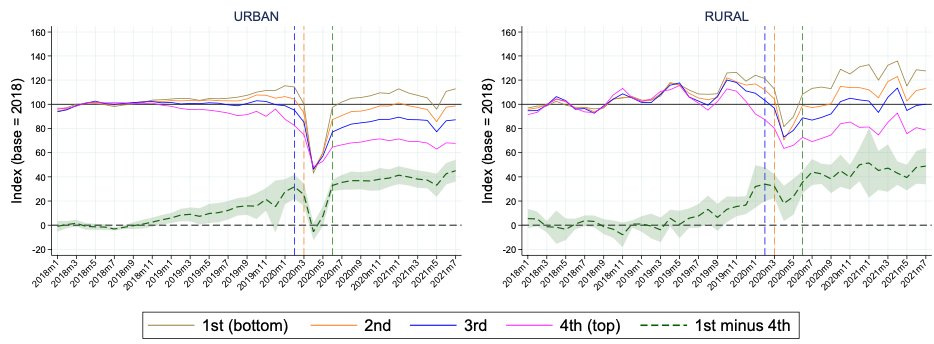

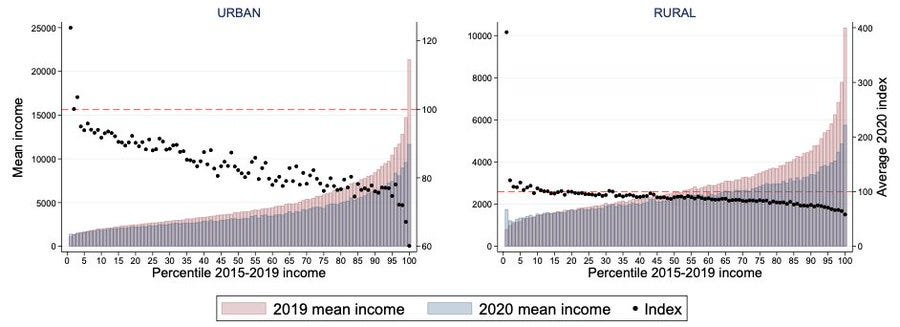

Does this higher poverty coincide with a regressive shock, in which the poor were hurt worse than the rich? Surprisingly, the answer is not really. Inequality actually fell after lockdown ended. We see this pretty clearly when we look at earnings across quartiles. The earnings of the bottom quartile ends up pretty close to baseline on average, while the earnings of the richest quartile remain persistently shocked well into the Delta wave in 2021. The pandemic, in other words, coincided with a progressive shock to living standards.

In fact, this shock is fairly monotonic across the income distribution. The better off you were before the pandemic, the worse you did during the pandemic.

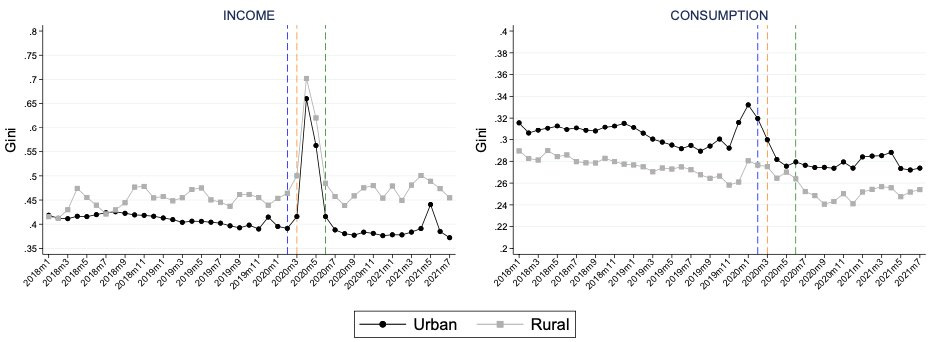

The Gini coefficient, interestingly enough, doesn’t fully capture this. The reason is that there was a ton of social churn at the same time. So many folks in the bottom quartile actually changed their position in the income distribution, while other people at the top fell in position. We can argue about how valuable this kind of churn really is, but there are a couple of takeaways here.

Static inequality measures like Gini give you a partial measure of inequality. You ideally need to combine longitudinal data to measure social mobility (the change in your income percentile, holding the percentile of income constant); in addition to static inequality measures. We can’t always do this, and usually resort to repeated cross-sections of inequality over time. But we might get a better picture by really seeing how people are doing over time.

Not all bad things go together! It’s easy to assume that because lots of other negative things happened in India, inequality might have worsened as well. But it’s important to look at the data and see what’s happening. The fact that inequality surprisingly went down doesn’t mean that things are somehow “okay” but, instead, it is shows the limitation in purely distributional outcomes in assessing welfare.

What Explains the Progressive Shock?

In the United States, we have a sense that the pandemic also wound up being progressive in the end; but particularly because the government sent in lots of stimulus in the form of direct checks, unemployment insurance, PPP (though that one might not have been as effective), in addition to relief brought by the Federal Reserve. This has led many people to think that the US has the full range of tools to not only avert serious Depressions, but to bring us back to full recovery quite quickly after a range of shocks.

This makes it interesting to examine India — which did not see nearly the same level of government transfers or support and saw a fairly stringent lockdown in the early phases (which had really negative effects on, say, urban migrant workers forced to walk back to villages). At the time, there were many worries that the poor would be simply unable to feed themselves. So how does this turn into a shock disproportionately affecting the rich?

The first thing to keep in mind here is that the rich actually tend to bear aggregate shocks in general. We see that in a range of work which has found that some of the richest people in the US have effectively a residual claim on economic output, and so do badly in recessions. We’re basically finding a similar result in India — the “rich” are bearing the brunt of the downturn. And by “rich” it’s important to have the right expectations. When we talk about the 80th percentile of Indians by income, we might mean a small shopkeeper who earns business income, and sees a large drop in sales during the pandemic.

A key part of this story is that *services* are really what got hammered hard during the pandemic. And it turns out that the rich in India happen to derive more of their income from this sector (as opposed to, say, agriculture) and consequently are harder hit. This kind of service income was protected in the US for many people who have remote work — but there just isn’t very much remote work in India, and so this population was badly hit.

The Pretrend in Inequality

Another interesting finding we ran into is that the decline in inequality, to a certain extent, starts before the pandemic. So the pandemic might be, to a certain extent, exacerbating some pre-existing trends. What’s going on there?

My speculation here actually goes back to demonetization — the experiment when Prime Minister Modi tried to combat corruption by outlawing all currency in circulation to force a recognition of corrupt earnings. As this money was recycled back into the financial system, it spurred credit generation in the non-bank financial system, which provided in particular more lending to real estate through risky short-term vehicles. This came to an end with a shadow banking crisis in 2019, just before the pandemic, which saw deep crises in home builders and firms like DHFL and Indiabulls (a bit like what China is going through with Evergrande and other real estate firms). In turn, it’s possible this episode was weighing a bit on high-end earnings even before the pandemic started.

A Complicated Shock

I know we are all thoroughly sick of this pandemic and a bit tired also at the wave of academic work that’s come out of it. But I think there are actually many important questions at the intersection of health and economics that remain somewhat open:

What really is “optimal policy” in these environments? Initially we had a sense that we were operating without tradeoffs essentially; because letting the disease run rampant would also destroy the economy. It seems like this has stopped being the case — when did things switch? Mass vaccination?

Should the full cannon blast of macro fiscal+monetary firepower become our default response to future pandemics? India’s experience — a pretty bad disease situation, not as much support, but surprising levels of private sector resilience and a coming recovery — maybe points to the fact that the pandemic would have been something like a “natural disaster” for developed countries even in the absence of more systematic support. A short temporary shock followed by recovery, as natural disasters do. Does that call for slightly less macroeconomic stimulus in pandemic environments (to avoid the inflation effects we are now seeing)? Or does it tell us that the problem of macroeconomic stabilization has basically been solved by a combination of helicopter drops of cash and monetary support?

Before the pandemic, a key result was that the Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC) was really high for many people, so that sending checks were pretty effective at boosting consumption. The standard interpretation is that this indicates how many people were really “constrained” by something. The checks this time around ultimately did boost consumption, but the MPCs wound up being way lower. One reason could be that large chunks of the economy (again, mostly services) were on ice for a long period of time, so the marginal dollar doesn’t go to consumption as much. But, if so, in what sense were people “constrained” beforehand? And will the recovery, as services open up, feature people spending all the excess savings they had stored up? One sign pointing to that is credit card debt has started to take off again, as the American consumer re-levers.

What’s the future of asset prices? If consumption was limited over the pandemic, it seems like people saved more; paid down some debts; and invested in stocks, real estate, and crypto. So are they going to pull out of the market to spend again as things reopen up? If so, does that spell an extended bear market for meme stocks, tech stocks, and all the crazy crypto stuff we have been seeing? Or maybe what’s going on is that future cash flows of pandemic-related services like streaming video, exercise bikes, and so forth are being re-evaluated as people switch back to consuming things in the physical universe. But then shouldn’t the prices of in-person service things be rising? Or is so much of that value held outside of public markets (ie, privately held restaurants)? Or is the issue really all about duration and how that’s impacted by Fed cycles of easing and contracting?