Recently I attended the Remote Work Conference organized by Jose Maria Barrero, Nick Bloom, Raj Choudhury, Steven Davis, Natalia Emanuel, and Emma Harrington. It was a lot of fun and well organized — and links to the presentations are available here. I wanted to write about what I learned about remote work from these presentations; which will leave out a bunch of other research but hopefully covers a bunch of the frontier work.

How Much Remote Work Is there?

This turns out to be a surprisingly difficult question to answer.

The BLS survey on this question unfortunately asks whether “teleworked or worked at home for pay because of the COVID-19 pandemic” and it appears people who work remotely for other reasons don’t always answer this question. The ACS takes a commute time definition of remote work based on what you did last week, and doesn’t cleanly separate hybrid and fully remote work. There are also tricky issues figuring out what’s going on with sole proprietors (who seem to work remotely a lot).

The remote life survey panel by Brynjolfsson, Horton, Makridis, Mas, Ozimek, Rock, and TuYe finds that about half of Americans work remotely some of the time, of which (as of October 2020) the bulk were actually mostly not in the office. Looking at this dynamically, this set of authors also finds that it is the “full time remote” population that generally switched to hybrid remote over time.

Lambert, Hansen, Bloom, Davis, Sadun, and Taska use job ads, and use some sophisticated algorithms to figure out what postings really refer to remote work — this shows that remote work appears to be here to stay, based on firm hiring decisions, and in fact variation across cities is widening. Aksoy, Barrero, Bloom, Davis, Dolls, and Zarate show how this varies globally — WFH one or two days a week is now common around the world, as the pandemic forced everyone to try this out at scale, and it worked better than people feared.

Kwan and Matthies also measure remote work creatively — looking at employee internet traffic, and classifying whether people are logging on at the office or at home. This also allows them to look at whether employees are shirking based on internet patterns — it doesn’t look like that, though people are working longer.

Does Remote Work Affect Productivity?

I think it’s fair here to say the evidence is a little mixed. The best evidence in favor of remote work comes from individual performance (ie, patent examiners) in developed countries with good broadband, new technologies (ie, asynchronous communications tools like Slack or Teams). There is a particularly nice paper here by Frey and Presidente who find that distributed scientific teams used to be at a disadvantage for outcomes like citations, which started to change in the 2010s; and now they are at an advantage.

The record in developing countries actually seems a bit more mixed.

Atkin, Schoar, Shinde find that remote workers are less productive based on an RCT in India; a gap which shows up initially, and grows over time (suggesting more learning at the office). However, Ranganathan and Das find more productivity in Kolkata, India.

Perhaps for some of these reasons, Brinatti, Cavallo, Cravino, and Drenik find that remote workers internationally are paid lower. I think there are three possibilities here:

The productivity story (international workers just less skilled). If this one is true, you might not see as much offshoring internationally.

Segmented job markets internationally. So the workers are just as good, but their wage pinned down by local labor conditions. They do find some evidence for this, which would predict more international digital work down the road.

Greater adverse selection in international hiring. ie some people are very good, but you might also get a bad worker and find it hard to screen ex ante. This one seems like a more fixable problem over time.

What’s a little less studied, but also super important I think, is how remote interactions influence contracting across firms. Alekseeva, Fontana, Genc, and Ranjbar find that distance matters less for accessing VC funding, as they basically figured out how to process deal flow in Zoom rather than through in-person meetings with Founders.

Why Don’t People Work More If it’s so Great?

So partially there is a selection story — remote workers historically were lower-productivity, so you get more lemons with your remote hiring plans: that’s the story in this justly famous work by Emanuel and Harrington (Though the story in India, in Atkin, Schoar, Shinde, is actually a bit different — there, more productive people select into remote work; and Indian remote working rates in the international survey in Aksoy, Barrero, Bloom, Davis, Dolls, and Zarate are high).

If you ask the managers, as in Lewandowski, Lipowska, and Smoter, they will basically say that they really think workers are going to be much less productive at home, and there are going to be large managerial investments required as a consequence. This opens up a large wedge between the pay gap workers are willing to give up for remote work (5%) and what employers expect based on their own expectations (40%). It seems like managers are pretty wrong here, at least on average, but this managerial expectation has been the key hurdle.

But there are other downsides to remote work too — at least the way it is currently set up. Emanuel and Harrington, along with Pallais, also find that remote workers seem to get less code feedback — even digital code reviews are complementary with in-person acquaintance, and this particularly affects women and younger workers.

Of course, a key limitation is that we are taking a technology (code reviews) honed in an era assuming a certain degree of in person interaction, and asking how it performs in a very different regime. So you might naturally ask how we might change how mentorship and advice generation works in a digital world. Choudhury, Lane, and Bojinov have a little negative result here — encouraging these virtual “water cooler” sessions doesn’t really do anything, with the possible exception of cases in which there is a demographic match between the boss and mentee.

Interestingly, that’s actually the same as what you observe when you look in person: speed dating for scientists only clicks in the presence of commonalities. So one implication here is that “virtual matchmaking” to try to organically generate the same links and culture that typically happens passively for in-person teams is possible, but requires a lot more work up front to figure out the right matches algorithmically.

Remote workers seem to have less worker solidarity as well, which Ranganathan and Das find, in the sense they are not as likely to go along with agitation for higher pay and different work conditions. Now, this research was done in historically Communist West Bengal, so you may well ask whether greater worker agitation is really helpful in that environment. You could also wonder whether an equilibrium in which workers use “exit” more often to express discontent rather than “voice” is better or worse for workers. But it certainly seems reasonable — and they also find, again in this developing country setting, that remote work is less productive.

Perhaps for some of these reasons, a bunch of papers come to the conclusion that hybrid work is a happy medium between fully remote and fully in person.

Choudhury, Khanna, Makridis, and Schirmann find that, when working days are randomized, hybrid work appears to generate the best composition for emails: the highest number sent, and the most informativeness of content.

Bloom, Han, and Liang conduct an RCT on engineers and find that hybrid work dramatically improves employee well-being and lowers quit rates. Productivity seemed up in this experiment as measured by lines of code. But this code isn’t like your Stata do-files: it’s production-level code, which the company seems to really monitor and evaluate as their own internal benchmark, and so again consistent with the broader idea that hybrid work seems to be working out.

What Does this Shift Mean?

The workhorse assumption in spatial models is that people work in the same place that they live. This was a pretty reasonable assumption until now, and it also means we had a fundamental identification problem in thinking about the growth of high-income workers sorting into superstar cities: were they following the jobs that existed in these places, or were the firms following highly educated workers who prefer urban amenities?

Now you can, more easily, live in a separate place from where you work, and the implications are actually pretty profound both for the location of economic activity as well as the level of some economic outcomes.

Delventhal and Parkhomenko have a very nice spatial model incorporating these shifts, which leads to predictions that economic activity is going to move out spatially within cities, as people commute in more infrequently. That’s consistent with work I’ve done with Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, Vrinda Mittal, and Jonas Peeters on how residential activity has shifted out to the suburbs and exurbs of cities; as well as work that we have on how office buildings are really the ground zero for remote work’s impact.

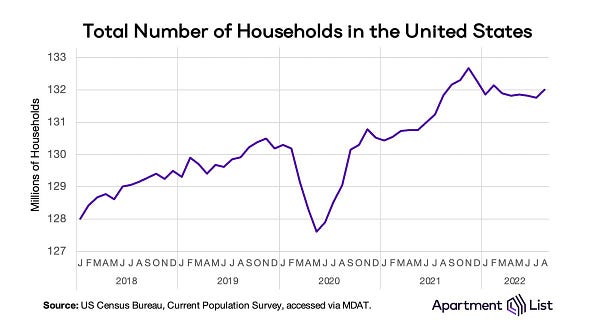

That increase in commercial value is a bit of a transfer towards residential units, where there has been an increase in household formation and space demand in the form of home offices, etc., leading to an increase in housing prices as Mondragon and Wieland find. Dalton, Dey, and Loewenstein also observe that changes in firm-level remote work results in less foot traffic as commutes drop, which then hits employment in other areas like accommodation and services.

Suburban wages also appear to be rising faster than urban wages, which Liu and Su find. Now, interpreting this result is a bit tricky I think. The authors suggest the agglomeration value of in-person activity is lower, so you have a productivity hit (and hence income) to urban professions. This is possible; but I think also imaginable that many professions are just moving out further into the suburbs and service workers are following them, as we’ve seen. A nice discussion of that paper here too.

Open Questions

So putting that together I think you can form a rough consensus on the state of remote work so far:

Many developing country remote workers are about as productive at home as in the office. At the least, there isn’t good evidence they are much *less* productive to the extent necessary to pay for office space, and managerial expectations otherwise are likely to get revised over time. However, in-person interaction still provides some essential benefits in terms of culture/mentorship/starting collaboration ties, and so some type of hybrid will persist. This means that cities, defined as large metropolitan units, are still going to be important — but the centrifugal pressure on economic activity will strain urban cores.

I think this is a fair read so far, but there are a bunch of open questions and issues for future research here I think:

What role is future remote work innovation going to play? The massive boost in remote work we saw was on the basis of relatively weak technology, compared to what’s in the works. Even if remote work stabilizes out at, say, 20% of paid work — that would serve as the basis of an enormous market, and so should fuel a ton of innovation to make this work better. Relatedly, you have the metaverse concept out there — and it’s easy to make fun of or downplay. But I think there is a serious enterprise use case to try to replicate as many of the features, online, that people really like in person. Just anecdotally, I’ve done some coworking on Gather, met some of those people in person, and I think that starts to get across some of the same benefits as in-person and you could imagine pushing those dimensions further.

How much do the benefits of remote work really require incentivized managers? The coordination hassles of remote workers — what days should they come in, what tasks should they work on — can be internalized by profit-maximizing firms, and management techniques adjusted accordingly. But one wonders about what’s happening with, say, Universities or government work. I think it’s at least possible that bureaucratic organizations aren’t really going to take advantage of the remote work revolution; because they are too committed to an older in-person monitoring technology.

Is hybrid work going to unravel in either direction? This could happen towards physical presence if “presentism” bias shows up: if the people who show up in person get more information or mentoring through in person communication, and get promoted more, it’s going to be harder to sustain remote work practices. By the same token, figuring out the scheduling challenges of hybrid work, and still being limited to workers in your metropolitan area broadly, limit you from really taking advantage of some fully remote advantages (like global labor force and no office spend). So maybe this is a bit of a stopgap arrangement.

What’s the Future of Work Going to Look Like? Relatedly, hybrid work sometimes looks to me like slapping on a motor on a horseless carriage. If you are already doing meetings in person; well you can do them virtually now and allow people the benefit of a day or two a week to do some deep work at home. But maybe this just reflects inertia on a stagnated technical form of work.

What would alternatives look like? Maybe fully remote workforces from the start, relying on global workforces. A much deeper and intermediated series of outsourcing arrangements, so that the Coasian rationale from firms breaks down a bit, given the ease of transacting externally for a variety of job functions, rather than delegating within the firm. Much more reliance on pair programming and pair working, together, rather than working in sequence. Or, again, a full retreat to the metaverse.How to algorithmically generate human connection? Think about online dating — which very quickly went from a a fringe choice, to the dominant way people meet their partners. It seems like there should be comparable benefits to connecting work connections — and if this gets good enough, maybe it would dominate the passive in person channel like what happened to online dating. The LinkedIn study finding benefits of algorithmically-generated “loose ties” is relevant here. I think this is especially important because whatever mentoring/collaboration etc benefits have taken off in person, have really just come across as mostly unintended byproducts of trying to monitor workers; so it’s hard to imagine, long-run, that it’s going to remain the dominant way of getting those benefits relative to pure-play innovations targeting exactly these benefits.

This Week in India

A collection of my threads on the Indian (occasionally Pakistan) economy: