What Happened at UIUC?

Are there limits to mass testing? Also—Strategic Rent Default and the Pace of the post-Covid Recovery

Let’s Talk About Illinois

So reopening schools fall into one of four categories:

Limited Testing, in Areas with Spread. See: UNC. These were the first dominos to fall. Also see: the University of Iowa—with over a thousand self-reported cases, and a situation that appears pandemic. Or South Carolina, where students were suggested to test on arrival (but not forced), where there are a thousand students now testing positive with a 28% test positivity rate. These situations are already disasters and there are no good options there for University Administrators. Do you send students home, and seed the crisis throughout the state, or would you rather keep students in dorms letting the disease spread throughout the entire student population? Whatever savings these Universities hoped to realize through dorm fees will be eaten up in Class Action Lawsuits in the years to come.

Limited Testing, Minimal Local Spread. As an example, see the CUNY system. NYC is one of the safer parts of the country right now—but the CUNY system is seeing ~230 cases according to the NYT University tracker. (York College for instance notes “Not everyone needs to be tested for coronavirus, according to the CDC.” 🙄). Temple University tested on arrival, but not subsequently—in the relatively low prevalence region of Philadelphia (3-4% test positivity rates). They saw cases climb quickly to over 100, causing a temporary shutdown (Temple does also have a number of commuter students). I think it’s likely these schools will deteriorate, but maybe over a longer time frame.

More Testing, Minimal Local Spread. These include schools in the Broad Institute Umbrella in the Northeast—BU, Harvard, Babson, MIT, Yale, etc.; Cornell, which put some thought in their reopening plan; and Chicago with a mass testing plan (and isn’t even on campus yet). So far these cases seem to be going well. Schools are generally finding low positivity rates, both on entry and on a continuing basis. BU’s test positivity rate from July 27 onward, for instance, is just 0.13%.

Which brings us to the last category: Schools with More Testing, but also More Local Spread. This is the category that UIUC falls into. The University had a really interesting twice weekly saliva testing I was a big fan of. But their latest numbers are not good: 429 students tested positive 8/31 and 9/1 earlier this week. Test positivity rates peaked over 3% last Sunday.

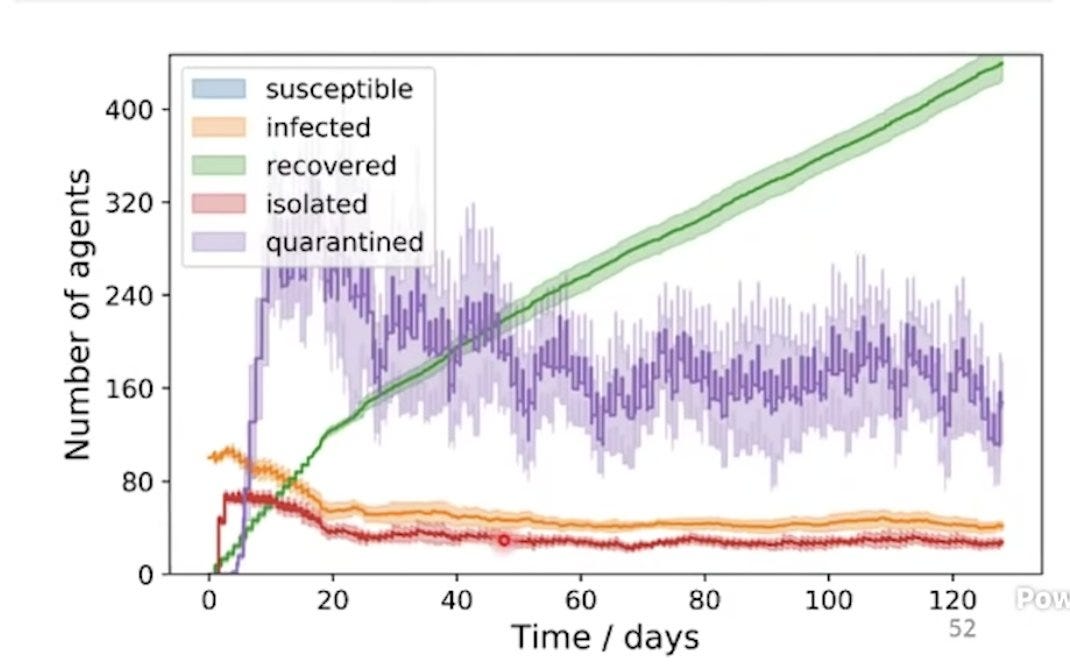

To put that in perspective—below is what the modelers thought would happen. An initial wave of cases as students returned to campus (Yup) followed by a steady decline with more than a hundred students infected at a time (Nope). Clearly the model failed somewhere. That’s a mea culpa from me too—I supported the UIUC plan, as it reflected the largest-scale deployment of a mass testing strategy (something I would like to see done around the entire country). So what happened?

I don’t think it’s helpful to just blame students. Clearly risky behavior and parties aren’t going to help the situation. But we need to formulate a plan robust to plausible student behaviors. It’s not like the modelers here didn’t realize that beer pong could exist; they note in the same slide as the graphic “Social life in bars/restaurants allowed.” So what else could be happening?

5% Inconclusive Test Rates. These happen in PCR tests when, after a number of cycles, the “amplified viral signal is of such a low level that it could potentially be a false-positive result.” Some students are reporting multiple invalid test results.

You don’t really see inconclusive numbers this high on nasal PCR tests, so it points to a possible problem with the saliva test used for mass testing purposes. One option would be to use PCR tests on entry, followed by regular saliva tests (as NYU is now doing), or transitioning quicker to a PCR test if a saliva one comes up empty. Obviously if some students aren’t being effectively screened the tests aren’t complete.Testing Delays. It seems that many people are waiting ~1 day to get back their testing results. This tempo leaves some time for things to spread.

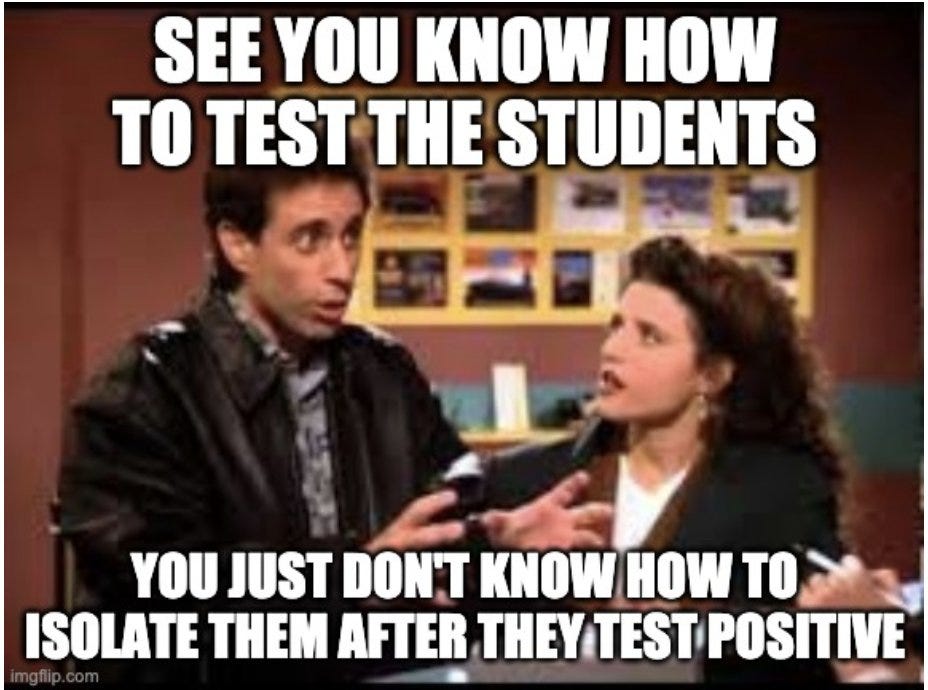

Lack of Immediate Quarantine. This seems to be the main issue. You hear of some students trying to “retest negative” going through the testing sequence a number of times, or just plain not doing anything after getting a positive test result. You also see more harrowing stories—which I would suggest reading in full—of what actually happens when you test positive.

It’s not fun. Even well-intentioned students do not necessarily have a clear path to isolation/quarantine (depending on whether they tested positive themselves, or were exposed to someone who was). Even though the UIUC modelers assumed fairly rapid spread—dorms are ideal environments for spread. Think prisons or nursing homes. Cases that linger in these environments, without rapid removal of cases, have the potential to spread much further, even during the 2x/week testing window.

This whole situation highlights that a central failure of the US coronavirus response has been not implementing more isolation facilities for those who test positive. This is something I’ve been interested in since late March—when some preliminary data out of China suggested that centralized quarantine was necessary to break household chains of transmission and get R < 1. We’ve borrowed the lockdown idea from China, but have never really done the quarantine. And University dorms kind of like much larger households, so this within-dorm spread channel can be quite important.

What to take away from this experience?

Most Universities are still either 1) in high-spread areas, or 2) not doing the testing they need to operate safely. They will continue to see escalating case counts and uncontrolled spread, which will spill over into the underlying communities and eventually their families.

Some Universities (primarily in the Northeast, since many CA schools are virtual) are operating in person in relatively safer areas with high testing volume; and I’m hopeful this will go better.

Other Universities (and ultimately firms, K-12 schools, etc.) are operating in riskier environments, and trying to control the spread through testing solutions. I remain optimistic that mass testing, i.e. through something like the Abbott test, can get this pandemic under control. But clearly it’s going to also require more quarantine/isolation capacity than we’ve been able to demonstrate so far.

Will Households Strategically Default on Rent?

The new White House/CDC rent moratorium joins a slew of local and state initiatives to slow the pace of evictions. These programs are motivated by a clear benefits—it’s better for individual tenants to stay in their unit and avoid getting kicked out as they experience income losses due to Covid.

But they raise a possible concern—will households face incentives to avoid paying rent, knowing that they will not face eviction as a consequence? I actually have some prior research on this in the 2008 Financial Crisis (along with Chris Mayer, Ed Morrison, and Tomasz Piskorski)—we found that households did strategically default in order to qualify for Countrywide’s mortgage modification program.

Richard Green sends along a nice survey in LA looking at this question today. Here is one key result—there are slight increases in rental delinquency among those who did not lose income, but the bulk of the delinquency is among individuals who also suffered income shocks or even had COVID.

Now, this gets into a semantic discussion about what “strategic” rental default actually means. My view is—strategic defaulters are those who fail to make payments, who would have made those payments had they faced different incentives. So while this cut across income gets at the ability to pay question; I think you would ideally compare these results with another comparable geography where borrowers had less of an incentive to default on rent (say, Texas) to really understand how much the forbearance plans are contributing to rental delinquency.

I think it’s fair to say that even borrowers without income losses are using some of the implicit insurance offered by their rental contract—they have the ability to delay payments a bit, or even miss a month here and there and avoid eviction, even if they ultimately make their payments. But, at least so far, you don’t see as much evidence of broad based rent non-payment. What accounts for the difference between this sample, and the Countrywide analysis did earlier?

A key reason seems to be that going delinquent on a Countrywide mortgage got you something—a modification that lowered your loan obligation. With rental forbearance plans—you still owe the money to the landlord. You are basically just extending the term of your repayment plan. Additionally, you have some security deposit (sort of the “collateral” in this case) which can go towards some missed payments.

So rental forbearance plans may not have the moral hazard consequences one might have feared. But more research is needed.™

Rapid Consumer Recovery?

Claudia Sahm sends along the following graph from OpenTable, which shows a pretty striking restaurant recovery in the UK (60% YoY increase in diners!).

The OpenTable data is a little weird and I would be curious if anyone has more insight into how it actually works. In theory, they track a set of restaurants which have opened up their entire inventory—so they should have a complete sense of diner count whether or not the person actually used OpenTable to book a reservation. It doesn’t seem to always line up with other data sources, but suppose you take it at face value.

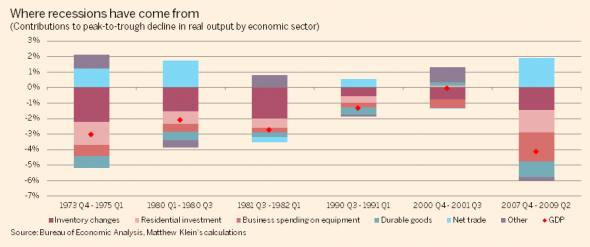

This, then, suggests that the Eat Out to Help Out Policy in the UK was pretty successful at increasing restaurant consumption. I think this is pretty interesting because we are seeing a lot of data points that suggest that real estate and durable goods are holding up pretty well. This is in stark contrast to the usual trend in recessions, as Matt Klein discusses, in which basically 100% of the decline in consumption comes from durable goods and real estate.

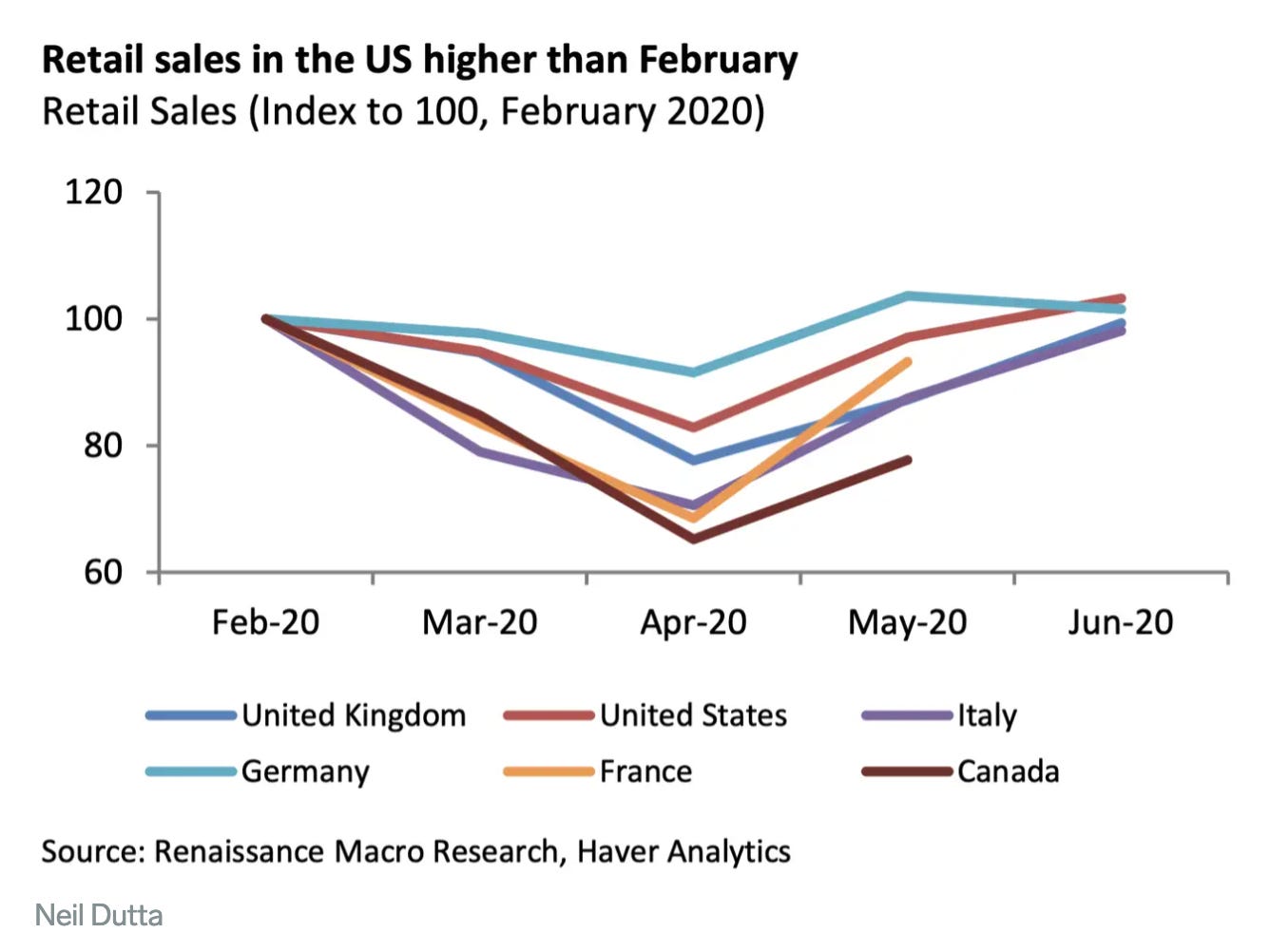

This time around—you can see retail sales recovering nicely, along with a nice V-shaped recovery in real estate. Services, and particularly restaurants, are holding back the US recovery.

And the UK suggests one possible solution—we could offer a targeted subsidy towards the specific sectors facing difficulties. You could offer a broad income stimulus instead, of course, but we know some of that will get saved. Instead, you can just make restaurant meals cheaper (the UK policy reduced restaurant meal prices by 50%). In principle, you could also give, say, everyone a $500 voucher that has to be spent on restaurant meals this year. It’s similar to David Andolfatto’s idea of hot money credits—but with a targeted sector focus on the parts of the economy that are lagging the most.

A key concern, of course, is that by boosting restaurants you might be inadvertently spiking Covid cases in sit-down restaurants. But as we get to a world in which we think indoor restaurants are safe to reopen (maybe you get your rapid test to clear you); I think it’s an interesting idea worth considering.

Other Links

Fed projects pretty quick consumption recovery from this crisis.

Really nice Stanford macro finance initiative. Highly recommended for PhD students.

Alice Evans has a great post discussing the persistence of the Indian joint family. India hasn’t followed the path of East Asian countries in as rapid expansion of firms and out-of-home work; the smaller scale of industrial expansion, through family business, has instead meant that India has avoided the nuclearization of family to the same extent. Even more broadly I would say that the slow pace of growth in market access and state capacity has meant that many goods are instead provided through caste networks. I think this is seeing really rapid change.

The virtues of Direct Instruction; which I still think might be interestingly applied to Zoom/virtual teaching.

Small firms saw the largest initial decline in the Covid crisis, followed later by a disproportionate drop among large firms.

Zumper data continue to show large rental declines in NYC and SF.