Labor Mobility, Monopsony, and Relationships in CLO Lending

Also the secular decline in rates and why there's so much vacancy in retail

It’s job market season here in the academic finance world, and I want to share some papers by my advisees, as well as other students here at NYU Stern. If you’re on a hiring committee — check them out!

Immigration Frictions Lower Labor Mobility and Produce Monoposony

The market power of firms on the labor side has received growing attention, as evidence has mounted that these frictions are enormously consequential and may have profound implications for understanding declining economic dynamism. The technology sector, which is responsible for so much of the fundamental innovation that drives economic progress, has been an area of particularly high concern over possible stagnation. Such worries are reflected in many time-series trends, including declining firm formation, lower rates of worker mobility across firms, and the seeming entrenched market power of incumbents.

But it’s awfully hard to figure out what frictions actually enables firm market power. People can, after all, switch jobs; and these days they are doing so pretty rapidly. So how can we measure the components of firm market power?

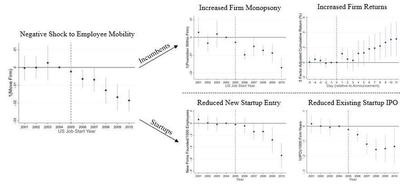

This is what Abhinav Gupta’s job market paper does. He looks at administrative changes which led to unexpected delays in the Green Card wait time process for Indian and Chinese immigrants after 2005, during which these immigrants find it difficult to change jobs. These changes were unexpected; only impacted the mobility restrictions on India and Chinese immigrants while in Green Card wait lines; and did not affect other nationalities, which serve as a control group. The end result is a difference-in-differences design which lowers only the labor mobility of a select group of immigrants, relative to unaffected other immigrants.

Employees for whom labor mobility is binding are much less likely to shift to other firms, consistent with the immigration system-imposed barriers on mobility. Indian and Chinese immigrants are 13% less likely to be promoted within their company after a shock to their exit opportunity. Indian and Chinese immigrants under the longer wait lines are also much less likely to join startups. We can see this in the mobility of affected immigrants to VC-backed startups (which declines by 15-20%), as well as examining new firm formation.

And finally — he is also able to trace the consequences of these frictions on firm value. These restrictions have large positive implications for firm returns, both in the short and long-run. So it’s a really neat paper which tangibly measures monopsony power and the (negative) consequences for employees and foregone entrepreneurs, as well as (positive) benefits for entrenched firms.

Changing the immigration system really seems like a win-win proposal. Improving the ability of immigrants who are already here to change jobs improves innovation and reduces the incentives for firms to rely on artificially cheap immigrant labor instead of domestic workers without actually changing total immigration numbers. There was a Mike Lee and Kamala Harris proposal at one point to alleviate some of this backlog. And the Visa Recapture provisions in the Build Back Better bill would make it easier for green card applicants to speed up their immigration process.

I think we are just beginning to understand the impact of immigration shortfalls on the labor market and other outcomes, and there’s much more research to be done here.

Lending Relationships in Securitized Loans

A lot of my teaching has to do with securitization, and I stress that this has natural benefits in the form of liquidity and risk sharing, but may come at the cost of lower screening and diluting the nature of relationships between banks and borrowers. When banks manage loans on their own balance sheets, the relationship winds up being pretty important and you have incentives to screen loans. But when banks just sell off these loans into securitized pools, you would usually expect that this sort of relationship doesn’t really matter. Corporate loans are really commonly securitized these days, which is leading to natural worries about what’s going on here.

Abhishek Bhardwaj has a JMP with striking evidence that this intuition does not necessarily hold, as relationships might still matter in the context of securitization. The ultimate reason is that by moving loans away from bank balance sheets onto capital markets, they are exposed to greater fire sale risk by institutional managers. There is a natural rationale behind this fire sale risk, which Abhishek uses for identification: credit ratings downgrades trigger the failure of CLO over-collateralization tests and result in forced sales. The central finding here is that banks’ business in underwriting the CLOs places them in a natural position to affect the selling behavior of CLOs in ways that prove to be quite important.

Banks use their relationship ties in order to provide insurance to firms against fire sale risk by leaning on their associated CLOs to avoid dumping relationship loans in the event of CLOs failing their over-collateralization test. A key reduced form piece of evidence which really documents this striking fact is that the composition of loan portfolios coming from relationship loans grows in the aftermath of CLO failure, as CLO holdings tilt in favor of relationship loans. Abhishek then goes onto to document the role for relationships in mitigating fire sale trades through a granular difference-in-differences approach which controls carefully for a variety of potential confounds.

This is a very nice contribution to the literature because it documents a novel role for banking relationships in helping to mitigate this important fire sale risk.

Abhishek also goes on to document the real effects of fire sales and therefore the benefits of relationship lending. While it might seem temporary consequences to loan pricing should not have much adverse impact on fundamental corporate activities, Abhishek documents that shocks in the secondary market of loan trades adversely affect firms’ ability to originate new loans. Loan issuance by firms whose debt is held by relationship fund managers, notably, is not affected — demonstrating both the value of relationships as well as the insurance they provide. This really interesting finding provides important additional evidence on the real effects of secondary market trading on firm outcomes.

Other Fun Papers

Sebastian Hillenbrand has a nice JMP finding that virtually all of long-term secular decline in interest rates has happened in a short window around FOMC meetings. I’ve talked about this really neat result before — the key innovation since is that he has a lot of new evidence that this is really driven by the market learning about the drivers of this secular decline from the Fed itself; and specifically the dot plots.

Daniel Stackman, from Stern Econ, has a paper on why there is so much vacant retail, especially in area like my neighborhood. The key idea is that nominal rent rigidity is baked into mortgage contracts through covenants, which require borrowers to ask lenders before they can lower rents. Borrowers are stuck with vacant properties because they can’t get their lenders to agree on rent reductions. Interestingly, you wouldn’t want to do away with these covenants entirely: they actually function to limit moral hazard and improve lender outcomes.

Germán Gutiérrez looks at the question which now FTC chair Lina Khan has made famous: how should Amazon be regulated? The standard consumer welfare view, arguably, isn’t well fit to address these broad platforms like Amazon, which sell products on their own as well as host other sellers. Eliminating Amazon Prime entirely makes consumers worse off, which is pretty sensible; but there are various interventions which increase competition, for instance in fulfillment, which make welfare better off.

Botao Wu looks at a question Matt Levine has often asked: what’s going on with corporate bond market liquidity? He argues that changes in regulation, especially Basel II.5, have really made the bond market less liquid, even though you can’t quite tell based on the bid-ask spread alone.

Youngmin Kim looks at investors with different reinvestment horizons. Historically, we have sort of abstracted away from the holding period that asset managers have in mind; but a big change in markets has been the growth in long-term asset managers like insurance and pension funds. These investors should care about whether these assets perform well in the future when other assets do poorly; which provides intertemporal hedging benefits. He finds this attribute is priced in equities and long term investors are overweight those hedging assets.