What's Going on with China's Stagnation?

Real Estate Boom-Busts and Soft Budget Constraints

The Narratives of Chinese Decline

Like you, I’ve been curiously reading headlines about the stagnation in Chinese growth, and wondering what’s going on. There’s an ongoing debate between two schools of thought behind why China is now facing growth hurdles, as Adam Tooze argues:

Authoritarian Expropriation Risk. China does not guarantee property rights or protect against seizing assets by entrepreneurs, and so can’t compel economic agents to put in effort. This is a view ascribed to Adam Posen, but my guess is that most economists would offer a version of this incentives story when articulating why only democracies (and resource rich countries) have passed the middle-income trap. I’d also associate Noah Smith with arguing that this is really a Xi Jinping problem, who has explicitly cracked down on all sorts of “soft” tech (video games, tutoring, software) in favor of “hard” tech, along with disappearing Jack Ma and doing a regulatory crackdown in general.

Structural Keynesian. This view, associated with Michael Pettis and Matt Klein, blames China’s growth weaknesses on structural imbalances — China is too dependent on investment relative to consumption. This means China has grown only by really pushing down marginal investment productivity. High savings channeled into these investments have been sustained by a weak social safety net, ensuring more precautionary savings, as well as financial repression which lowers household deposit income in favor of lower firm borrowing rates.

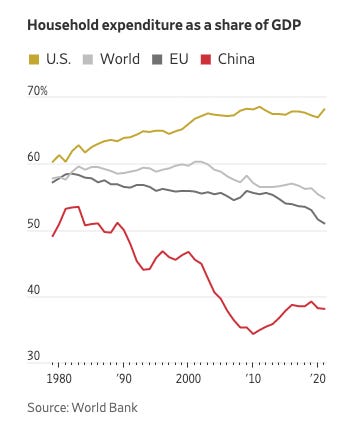

Some evidence for the “imbalances” view comes from looking at household expenditures directly — China has an incredibly low (though growing since 2008) share of GDP accounted for by household expenditures. This reflects high investment, funded both by high savings rates as well as high debt.

I think there’s merit in both “orthodox” explanations behind China’s decline. The main challenge with the “expropriation” view is that there are surprisingly no obvious signs for incentive problems in China holding back wealth generation — R&D spending is huge, entrepreneurship is massive, and China is home to more large digital platforms (Alibaba, etc.) than Europe. Maybe billionaires are a bit overconfident — or else have a foreign visa escape valve — so this problem hasn’t been binding so far.

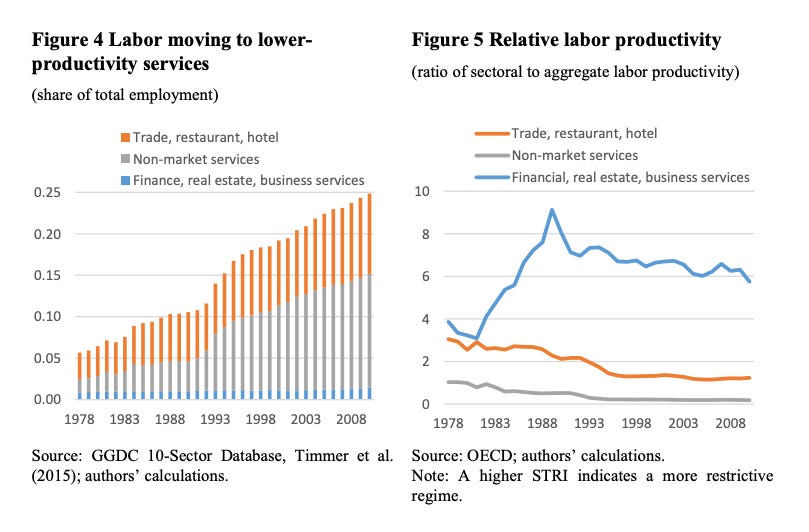

One of the challenges I have with the “imbalances” view is that it’s not obvious how greater domestic consumption spending is going to further future productivity growth. China has already seen substantial movement of labor to low productivity service sectors like hotels, restaurants, etc. Even more so than real estate construction (more on that in a bit) these non-tradable services have really bad productivity growth.

This is just Baumol’s cost disease in action — low productivity sectors tend to gain in labor share over time. But shifting incremental GDP from investment to consumption would, presumably, accentuate that problem by reducing factory output and increasing spending in sectors like hotels or restaurants which are unlikely to see gains in productivity growth.

Relatedly, it looks like there is still room for China’s government and private capital stock to grow, relative to the most developed countries. So again it’s not ex ante obvious that the “investment over consumption” strategy is prone to structural weakness. Finally, another challenge to address this is that fiscal capacity, especially by local governments, appears low given high indebtedness, suggesting a limited scope for traditional Keynesian stimulus, at least at local levels.

Given that, it’s worth considering two other stories that are relevant here.

The Real Estate Boom Story of China

The Real Estate Boom-Bust hypothesis for China’s growth — I’d again associate Noah Smith with this as well as Ken Rogoff — is the idea that China only kicked the can down the road in 2008, allowing a real estate bubble to temporarily goose up the economy. But now this is heading for a crash, and China may be headed for years of weak growth ahead — like Spain (which you can see on the graph had a really pronounced boom-bust cycle), or Japan earlier. Karsen Müller and Emil Verner have a paper arguing that credit expansion to non-tradable sectors, like real estate, are associated more with financial instability and boom-bust cycles.

Overall, it seems clear that China’s economy, capital stock, and financial systems have all increasingly been linked to real estate and infrastructure. This entails conceptually distinct, but related, problems with real estate overdependence:

Low Construction Sector TFP Growth. This is really a problem with the quantity side of real estate: the idea that the big issue is pouring resources into the construction sector, which faces systemic barriers to improving productivity (see this paper by Yu Shi for instance). Low construction productivity growth is certainly well noted in American data; but it’s actually hard to tell whether the same is true in China, and more importantly to figure out why construction productivity is so low. There’s no inherent barrier to adopting a more factory-style prefabrication approach to construction which can see productivity growth, and indeed China seems to be innovating a lot in that direction.

The Price “Bubble” in Real Estate. This is a problem more with the price side of real estate — the idea that the value run up in houses stimulates excess consumption, an appreciation in real exchange rates, and hence too much unproductive consumption. You hear this story for the Spanish and American real estate booms as well, but note it’s the complete opposite of the “imbalances” view earlier, and would predict too high consumption in China. More broadly, you can think of the housing boom in general as capitalized consumption, which itself complicates the story of China as underconsuming; investing in construction today is enjoying housing services as consumption tomorrow.

Malinvestment. This one is illustrated by all the occasional stories about “ghost cities” and so forth in China, and is worth being a bit critical about it. A decade ago for instance, you saw some viral videos about Ordos as a “ghost city”; illustrative of this supposed empty apartment boom. Today, Ordos is a booming city of over two million and those apartments seem like a good idea. More broadly, while real estate prices remain extremely pricey in the very top metros — affordability has actually been coming improving in second and third tier cities, with more supply coming online and incomes rising quickly. Overall, it’s still debated whether China built way too much; whether the building boom was necessary but now no longer needed; or whether China’s structural transformation is ongoing and will require even more building.

Too much Leverage. This strikes me as the most plausible real estate channel. The problem with real estate is that the construction, banking, and household sector take on a lot of debt to finance real estate investments, and so the collapse in real estate produces banking and balance sheet problems that linger for years. In principle this problem could be addressed through transfers and fiscal stimulus — or through raising property taxes which provides additional revenue streams to local government while lowering property values. But these seem politically challenging reforms, and threaten in particular the Communist Party monopoly on power, which I’ll come back to.

Overall the real estate problem does seem compelling; and it’s hard to argue against the experiences of Japan, Spain, and so forth in viewing China as facing a big potential hangover.

Still, there is something a bit unsatisfying in ascribing China’s demise as originating in the successful production of houses and high-speed rail lines. After all, these are achievements that we’d love to have in the US; are surely essential investments that need to happen anyway; and also presumably assist with growth. So there’s another narrative that can be helpful.

Soft Budget Constraints

János Kornai is one of the great thinkers to come out of the Soviet Bloc, and his diagnosis for what went wrong there — the soft budget constraint thesis — is also relevant for thinking about China. This is an account that puts the authoritarianism and political economy problems at the heart of China’s growth problems.

Usually, when we think of the Hayekian information problems facing communist governments, we think about lack of prices and signals to coordinate production across firms. Kornai’s formulation has the key problem being inside firms, about how management internalizes and deals with price signals. The core problem is that loss-making enterprises (whether formally public or private with public characteristics) are not allowed to fail, and this expectation infects all firm decisions. You end up in a chronic situation of “shortages,” because firms all get bailed out, and continue operations as zombie entities (and demanding more inputs) long after financial viability. And the Party can never commit to doing the hard market reforms here, which would inevitably lead to ending political rule.

Okay, what evidence is there for this in China?

Looking across manufacturing firms, TFP is down substantially in the post-GFC window driven by two factors. First, TFP growth of new firms is down a lot, suggesting that firm entry has become less dependent on purely economic factors. Second, we see the TFP growth from the exit dimension is negative — improving productivity by removing unproductive firms isn’t happening in China. That’s actually a very different story from developed countries, where TFP of existing plants remains similar, but unproductive firms exit over time, raising productivity. There are also problems with SOEs, as this report documents:

In 2003, the State-owned Asset Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) was created with the goal to preserve and increase state-owned assets through restructuring and consolidation. In line with other studies (e.g., Brandt and Zhu, 2010; Hsieh and Song, 2015), our results show that labor productivity and efficiency at manufacturing SOEs improved after 1998. However, our findings also show that industrial SOE performance—both in terms of efficiency and financially—worsened after 2007. According to the multitask theory of SOE reform of Bai et al. (2006), SOEs are assigned a mix of commercial and policy objectives. As a result, SOEs play an important role in macroeconomic stabilization, maintaining social stability, investing in public infrastructure and in underdeveloped regions, which has come at the expense of financial performance. To be able to provide these public goods, SOEs have benefited from soft budget constraints, i.e. preferential access to government subsidies, tax exemptions, credit, and land (Kornai et al., 2003). The deterioration in SOE performance could be related to the fact that SOEs were called upon to fulfill their public policy objectives in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

Under this view, China’s growth decline is fundamentally a political problem; not one of inducing entrepreneurs to work harder, but in the inability to enforce market discipline and allow the appropriate functioning of price signals. These problems have large external consequences, because China’s SOEs are also disproportionately responsible for carbon emissions: the same insensitivity to price signals limits the internalization of climate spillovers.

Ultimately, I think all four stories likely play a role here. But I think this last story — one that China in the same category as Communist countries which were able to grow and achieve some structural transformation, before ultimately flaming out due to fundamental political economy problems — remains undercovered in discussions that think of China as just another country,

What’s common across all these narratives is that China’s growth story may be more brittle than commonly accepted, and to fix it may require politically challenging reforms to both the underlying economic and political model.

Finally — in the spirit of nuance as we did last week with Europe, it’s also worth contextualizing these points of stagnation within a remarkably successful Chinese economic system. The rapid period of economic growth in the last several decades is one of the best things to ever happen to humanity; and China remains a very high performing economy on many dimensions: not just traditional sectors of manufacturing, but also increasingly in renewable energy and EVs; in airplanes; as well as in frontier scientific, computing, and tech sectors like AI, semiconductors, digital platforms, and so forth — far beyond what most economists would have thought possible under a Leninist one-party state.